1. FLASHBACK

Le Dau tried to kill me. This was 1965—Da Nang, South Vietnam. He had planted a bomb under the seat of the booth where I usually sat every afternoon around 5:30 p.m., in the bar of Grand Hotel. The bomb consisted of two and a half pounds of plastic C-3 explosive molded into a black transistor radio and concealed in a Japanese Airlines flight bag.

Not understood by Le Dau, who was simply the deliveryman, the bomb had a chemical fuse. The Viet Cong didn’t usually go to that kind of expense and complication. They just wired a pen-sized detonator stolen from the U.S. military to two AA flashlight batteries and then to a cheap watch, minus the minute-hand. When the hour-hand touched the inserted metal post on the watch face, the electrical circuit was completed and the bomb exploded. But a chemical fuse took more time and wasn’t as precise.

When I didn’t arrive at the expected time and the bomb didn’t go off, Le Dau returned to see what was wrong. Nothing was wrong, the chemical fuse was activated and since I had been delayed for only a few minutes, I would have been vaporized. But his return aroused the suspicion of a waitress. She alerted the South Vietnamese military police. They grabbed Le Dau and defused the bomb just as I arrived on my Vespa scooter.

I couldn’t be certain but I was pretty sure I was the target. The Grand was a French hotel and the only patrons at the bar were usually Corsicans who weren’t logical communist targets. In fact, the Corsicans were known to cooperate and even collaborate with the VC. That’s why I dropped by every afternoon, to have a drink and a chat with them. I was trying to pick up info about what the VC were planning, which was part of my job as chief of covert military intelligence in Danang. If the VC had wanted to knock off a bunch of Americans, they could have set the bomb near the Officers Club, a few blocks away, where security was lax.

|

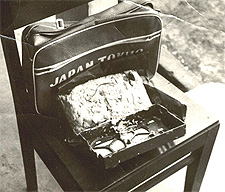

The bomb planted under my booth.

(Photo-ZG) |

|

I tried to stay calm and to think through the scenario. Were the Viet Cong really behind this? Anything that happened was immediately blamed on the VC, and I knew this wasn’t always the case. My next-door neighbor had recently been shot in the head by two guys on a motorbike as he pedaled home on his bicycle.

Everybody said, “Viet Cong!” But it looked to me like somebody might have been wiping out a family debt. You could get whacked for any reason and there was never an investigation.

Was it possible, I wondered, that somebody else could be after me. That didn’t take much reflection. There was. A few days earlier a neighbor had accused me of having sex with his wife. I had a big ground-floor room, detached from the other rooms of the villa, which I used as an office/bedroom, and that’s where he came to see me.

He was taller than the average Vietnamese and well muscled. When I opened the door, I saw that he was covered with sweat and his eyes were pinpoints of anger.

“Mr. Yip, can I talk to you?” he asked in Vietnamese.

When I arrived in Vietnam in 1964, the chief translator for my intelligence unit suggested I take the Vietnamese name “Diep.” As a northern refugee from Hanoi, he pronounced it “Zip,” which was okay by me. But I discovered that southerners pronounced the “D” as a “Y” so I became known by the silly name of Yip to the Vietnamese I dealt with.

“Sure, come on in,” I said.

“Mr. Yip, you cannot do this. The neighbors are talking. I cannot let you do this.”

“Do what?” I asked.

He giggled in a high-pitched way that prickled the hairs on the back of my neck. I knew this sound. The Vietnamese made it only when they got excited or nervous, and usually when they were about to commit an act of violence.

“Mr. Yip, you close your bedroom door when my wife comes to give you a Vietnamese lesson. What is going on? I cannot let you do this.”

He kept looking at the bed behind us as he talked and giggled. On the table next to my bed was a Swedish-K submachine gun, loaded and cocked, and six M-26 grenades. If he made a dash for my weapons I was in serious trouble.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I closed the door to keep the mosquitoes out. I’ll keep it open from now on.”

“The neighbors are laughing at me, Mr. Yip.”

This guy thought I was screwing his wife—which I wasn’t. And he really wanted to kill me!

“Okay, okay, I promise it won’t happen again,” I said, nervously. “I’m very sorry they got the wrong impression. I apologize.”

He calmed down. But he was still very angry when he left.

Le Dau, I later found out, was a 27-year-old fisherman and a low-level VC. My neighbor was a supervisor in Danang’s fishing industry, and it wouldn’t have surprised me to find he was a high-level VC. That didn’t quite complete the circle but it made me suspicious.

On the other hand, maybe the Viet Cong wanted to send a message to General Nguyen Chanh Thi not to count on Americans who could be easily blown away. I had become especially close to Thi, who ruled the upper part of South Vietnam like a warlord. Thi was charming and straightforward and I liked him a lot, though I thought he had more guts than brains. But that was better, as I saw it, than many politically appointed generals who had neither.

In any case, I was extremely anxious to get a chance to interrogate Le Dau. And I hoped to do it before Thi’s intelligence officers got their hands on him. I admired his combat officers. They were tough, brave, and good at their job. But his intelligence officers knew no language but torture.

I didn’t think they were psychopaths, as many torturers were. I thought they were simply incompetent. They didn’t know how to conduct an interrogation. Their preferred method was waterboarding, followed by attaching an electrical charge to the prisoner’s testicles. Women were treated the same way, except the electrical wires were attached to their breasts and fingers.

Eliciting information from anyone, whether through an interrogation, or through a newspaper or business interview, required more than just learning a few basic techniques. Experience and intuition and an understanding of human motivation were also necessary. The successful interrogators of World War Two who saved untold thousands of lives later called interrogation an “art form.” I couldn’t argue with that, it was something you really had to work at, and instructions found in a manual were worthless because every case was different.

I hopped on my Vespa and rushed to General Thi’s city headquarters, where Le Dau had been taken. Thi arrived at the same time. He jumped out of his jeep and went inside. I hesitated several minutes to calm myself down. I didn’t want the Vietnamese to know I was taking more than a routine interest in this case.

When I went inside, I saw Le Dau standing in a circle of Vietnamese officers. He was not shackled or bound. The Vietnamese surrounding him were in a frenzy. The noise of that weird giggle, the harbinger of violence, arose from the group, as General Thi took over the interrogation.

Thi grabbed a billyclub club from a military policeman and began asking questions. No matter how Le Dau answered, Thi cursed him and hit him on the head with the club. This went on for several minutes. I stood in the background, silent.

I hated torture. I knew of no American who didn’t. U.S. combat soldiers killed in battle but they didn’t murder—there was a difference—and if they did, they were held accountable. Intelligence officers didn’t torture—and if we did, I thought we should be held accountable, too.

This didn’t mean that we were softies or in the least sentimental about what we were doing. It meant that we were part of a disciplined U.S. Army which lived up to American ideals. In fact, I was far from being a pacifist. The real reason I was anxious to interrogate Le Dau was so I could pinpoint who was trying to get me. Then, I knew, my best Vietnamese friend would try to get them first.

My friend and I were the same age and same rank and we called each other Lieutenant. He was known as the bravest officer in Danang, a member of the elite Black Panther Rangers. General Thi used his unit only for the most dangerous assignments.

|

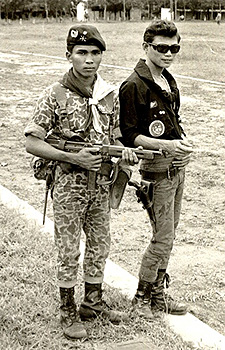

My friend (right) and his bodyguard.

(Photo-ZG) |

|

Lieutenant knew he eventually would be killed. But he wanted to go out in a blaze of glory, like his beloved American cowboys. General Thi loved cowboy movies too and treated him like a son. Lieutenant told me to let him know and he would kill anybody who was trying to kill me.

I knew that General Thi was reaching his explosion point, the culmination of this “interrogation” that was simply an excuse to vent their anger on a terrorist. Why didn’t I intervene? And get shot? We gave the Vietnamese money—I passed out thousands of piastres to intelligence officers each month—but we didn’t control them. First of all, because they didn’t believe we were in Vietnam to help them but to help ourselves.

|

| Gen. Nguyen Chanh Thi. |

|

Finally, General Thi cracked Le Dau across the face with the billyclub. He fell to the floor, unconscious. Thi turned and left, followed by the other officers. I could see Le Dau’s head swelling up, as if someone was inflating a balloon, a breath at a time. I knew he wasn’t going to die and I left him lying on the floor.

Next day I went to see Le Dau, accompanied by the major who was head of Vietnamese intelligence in Danang. I asked him a question. He didn’t reply, he just stared at us. The major started to prod him.

“No, wait,” I said. “He can’t talk. I think his jaw is broken.”

It was.

I decided to confront the major head-on. Not only had the Vietnamese done something ethically and morally wrong, they also had been incredibly stupid. How could we get any information out of someone with a broken jaw?

The major looked at me coldly as I spoke. After I finished, he said, “You Americans have your way of interrogation and we have ours.” Then he turned and walked out, leaving me alone with Le Dau.

|

Le Dau the day after General Thi‘s "interrogation."

(Photo-ZG) |

|

I had complained to my headquarters in Saigon about the torture Vietnamese intelligence officers were using. Since I worked closer than any other U.S. intelligence officer with a major Vietnamese command, I had probably witnessed more waterboarding and electric shocks and beatings than any American in the war. Nothing had come of my complaints. But I thought Le Dau’s case gave me a good reason to fly to Saigon to meet personally with my unit commander.

I liked my commander. He was a decent man whom I knew had never—and never would—engage in such tactics. But the war was just taking off and he was trying to create an effective intelligence unit—which meant getting along with the Vietnamese and nudging them forward. After hearing me out, he told me I was right and maybe he could do something soon to correct the torture problem. He said he was developing a good rapport with the newly assigned head of South Vietnam’s military intelligence.

“Zip, we’re finally getting them to move,” he said. “The new chief is outstanding. He drinks Bourbon. He’s brave, smart, and just an all around helluva good guy. His name is Nguyen Ngoc Loan.”

Loan was the general who was later photographed as he shot a Viet Cong in the head during the 1968 Tet Offensive.

The Vietnamese realized they had made a mistake with Le Dau. It became widely known that they had beat and tortured him without getting any information. I told plenty of people that Thi broke his jaw, though I continued to maintain my close working relationship with the general. In fact, I later went to see him after he lost out in a power struggle and was exiled to a Washington high-rise and a CIA pension. He complained to me about the cold weather and the lack of new cowboy movies.

At Thi’s headquarters they decided it was best to erase their mistake. My friend, Lieutenant, commanded the firing squad. A truck with ten soldiers drove to the Danang soccer field at 1 p.m. on that blistering day. They jumped out and took up firing positions, five kneeling in front, five standing behind. Another truck rolled up and two soldiers leaped out dragging the blindfolded Le Dau. They shoved him to the post. As soon as he was tied, Lieutenant gave the word. All ten shots smashed into his chest.

I never did find out whether someone had targeted me for assassination or whether it was just a coincidence. And Lieutenant and his bodyguard did not go out in a blaze of glory. They were killed in a VC ambush a week later.

|

At Le Dau's execution—Da Nang 1965.

(Photo-ZG)

|

|

2. FLASHFORWARD

When the controversy surrounding the U.S. torture of Al-Qaeda prisoners exploded 40 years later, I flashbacked to my experiences in Indochina and to what I had later seen as a journalist in Lebanon and Jordan and Egypt and Greece and other countries. I could not believe the United States of America had begun to use torture as a matter of official policy.

Furthermore, it appeared the policy had the support of many Americans. I found this mind-boggling.

What happened? How did it come about? Of course I understood that the American psyche had undergone a seismic shock from the horror of 9/11. But why the rush to embrace tactics used by the Nazis and Stalinist Russia?

I began to realize that many Americans had been. . . what?—persuaded? brainwashed?—by Hollywood and Television to believe there was only one kind of terrorism and it involved a bomb set to go off. In every show the incredibly tense countdown began as the camera focused on the bomb’s red digital clock with the seconds and minutes swiftly passing until the moment we would all be blown up.

Now, who wouldn’t use torture or do anything else to stop that bomb? I certainly would and so would any experienced intelligence officer. In a case like that, it didn’t have to be codified by law that you should take any measure possible to keep America from being destroyed. It was simple common sense.

The problem was the ticking bomb was a melodramatic device to create fear and tension in a movie to generate big bucks at the theater or on TV. The hero inevitably dismantled the bomb at the last minute, with viewers going “Whew!”

In fact, 99 percent of intelligence work did not involve ticking bombs or imminent threats. In most cases the work consisted of piecing together small and seemingly disparate facts until eventually a clear enough picture emerged that allowed trained professionals to stop ticking bombs and imminent threats before they developed. And as most people who worked in intelligence knew you didn’t torture to get that information.

“Why not?” one might ask. ”Were Bush and Cheney lying when they said it worked?”

Oh sure, it worked. To a degree. You tortured somebody and they’d give you a little information. But they’d also give you a lot of lies. Think about this: Why would you interrogate somebody if you already knew the answers? And if you didn’t know the answers, how would you know whether they were telling the truth? A lot of it couldn’t be checked out.

Collecting intelligence involved hard, patient, and painstaking work. And it could all be ruined by trying to use a shortcut.

But taking a shortcut was what President George W. Bush decided to do. Apparently he believed there was a ticking bomb or an imminent threat ready to go off at any minute. And the number one man who encouraged him to believe that was Vice President Richard Cheney.

3. DICK CHENEY & FEAR CONTROL

Dick Cheney came under criticism for his stand on torture, especially from the Left. People called him all kinds of names—psychopath, crazy, fascist. But military men, former or active, who had served in a war, quickly recognized that Cheney’s problem was not at all unusual and that it didn’t make him a psychopath.

It simply made him a man who did not have good fear control. Cheney spoke calmly but he did not act calmly. And military training was designed to identify men like him.

Fear is a normal response to combat. The question was not whether you were afraid, the question was whether you could control your fear well enough to act and think calmly in the face of threats or when somebody was actually trying to kill you.

Some people couldn’t.

The military knew that putting an officer who was inclined to freeze or panic in a leadership position would likely get the people under his command killed. This didn’t mean the officer was not suitable to hold other less sensitive positions.

|

| Fear Control? |

|

Of course Cheney didn’t undergo military training, where his problem would have been recognized. He made five official requests not to be sent to Vietnam, at the time his age group was serving in the war. This did not in itself indicate his level of fear control. Plenty of young men Cheney’s age avoided serving in Vietnam and not all of them were simply fearful of being killed.

But Cheney continued to show a pattern of fear-control issues, which rose to the forefront of his personality after 9/11. During the following years Cheney’s frequent disappearances to an “undisclosed location”—thought to be a bunker—became a national joke. He refused to appear in public except under tightly controlled circumstances. He never took a spontaneous walk or drive. It seemed to be one more indication of his inability to act calmly when he shot a friend while bird hunting.

Cheney didn’t seem to realize—or perhaps care—that his advocacy of torture put the lives of future generations of America’s servicemen and women at risk. It wasn’t by accident that no U.S. military leader supported torture. In fact, they stood outspokenly against it. And the reason was simple. They knew that perception and propaganda played an important role in every war.

The only propaganda victory the United States won in the Vietnam War concerned the use of torture—by the North Vietnamese, not us. The U.S. was able to mobilize an international campaign against the Vietnamese for torturing our prisoners of war in Hanoi. The Vietnamese finally yielded to pressure and all but stopped the torture. Unquestionably, American lives had been saved.

What would happen now?

4. The Worst CIA Director Ever

Cheney wasn’t the only one to put future American lives at risk by his advocacy of torture. Several CIA directors were also responsible and were also—not coincidentally—men who were like Cheney. George Tenet, of course: the slam-dunker who took a manly pleasure in killing terrorists, so long as he could do it by pulling the trigger on a Predator drone from thousands of miles away. Tenet, a Hill politician, wasn’t much for military service either.

But it was Michael Hayden, in my opinion, who was hands-down the worst CIA director ever. And I believed the negative result of his tenure would be felt for years.

|

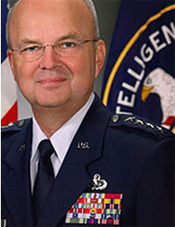

| Michael Hayden—Worst Ever? |

|

An interesting comparison could be made between two CIA directors, William Colby and Michael Hayden. Colby was physically unimpressive. So was Hayden, which is probably why he insisted on wearing his air force uniform as CIA director, to try to conceal that fact with ribbons. Both of them spoke quietly and politely. There was no bluster or swagger to either one.

But William Colby had joined the OSS in World War II and parachuted into Europe to organize a Nazi resistance. Throughout his career Colby was known for his courage. He volunteered for Vietnam and never hesitated to put himself on the line. He was also known as the father of the Phoenix Program, whereby Viet Cong were hunted down and assassinated. Behind his polite demeanor, Colby was far from being a soft guy.

Michael Hayden was a four-year Air Force ROTC student who was required to serve after he graduated from college in 1967. At that time the Vietnam War was going full blast. Hayden, however, like Cheney, was not interested in going to Vietnam. Instead, he finagled a deferment to get an MA degree in “Modern American History.” One could ask: What was more modern or more historical than the Vietnam War?

The first half of Hayden’s career was mediocre and he seemed headed to retirement as a lieutenant colonel. It took him nine years to advance from captain to major, and he only met with success by finally hitching his wagon to a former Vietnam pilot who was on his way up. There was no evidence that Hayden had ever interrogated anyone. He was a gadget guy. His specialty was reading electronic intercepts and listening to wiretapped conversations.

So which one supported torture? Hayden, of course.

Colby told me in a tape-recorded interview that he believed based on everything he had ever seen that torture did not work. He said this was the attitude of intelligence officers he knew but no one wanted to state it in such direct terms. They were afraid, he said, that the inference might be drawn that they would use torture if they thought it worked—which would make it sound as though they were ignoring the immorality of the practice.

Fear is a communicable disease. I realized this is why Cheney and Hayden had succeeded in convincing so many Americans to forego their values and support torture. Both of them declared the terrorists were going to get us and we had no choice, we were metaphorically sitting on a ticking bomb. They sounded, and undoubtedly were, sincere in telling us about the disaster we faced.

There was indeed real danger out there. Everyone knew it. But Cheney and Hayden’s insistence that the U.S. use torture said more about themselves than the level of the threat. It was all about fear control.

Theirs.

|