That sounds like a pretentious title. Even presumptuous. "The War and

I." My father, who saw combat through the worst days of World War Two--in

North Africa, Italy, France, Belgium--and was critically wounded at Bastogne,

would have never personalized his participation. He took pride in viewing himself

as a part of the "Good War," simply a patriotic American who had served

with other men exactly like him. He asked for nothing in return except to be

honored with the U.S. flag draped over his coffin.

He was.

But the Vietnam War did not work out that way. It was such a debacle that if

you didn't come out of it with your own personal story, you came away with nothing.

And so my generation's war has produced a million different stories of how the

conflict affected the individual.

That is the reason, I believe, the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington has become

so important to so many. You go to The Wall to touch a person, not a cause like

the "Good War."

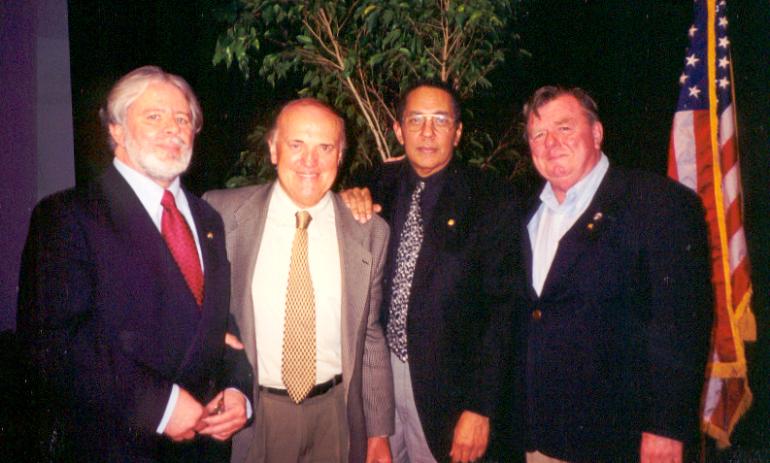

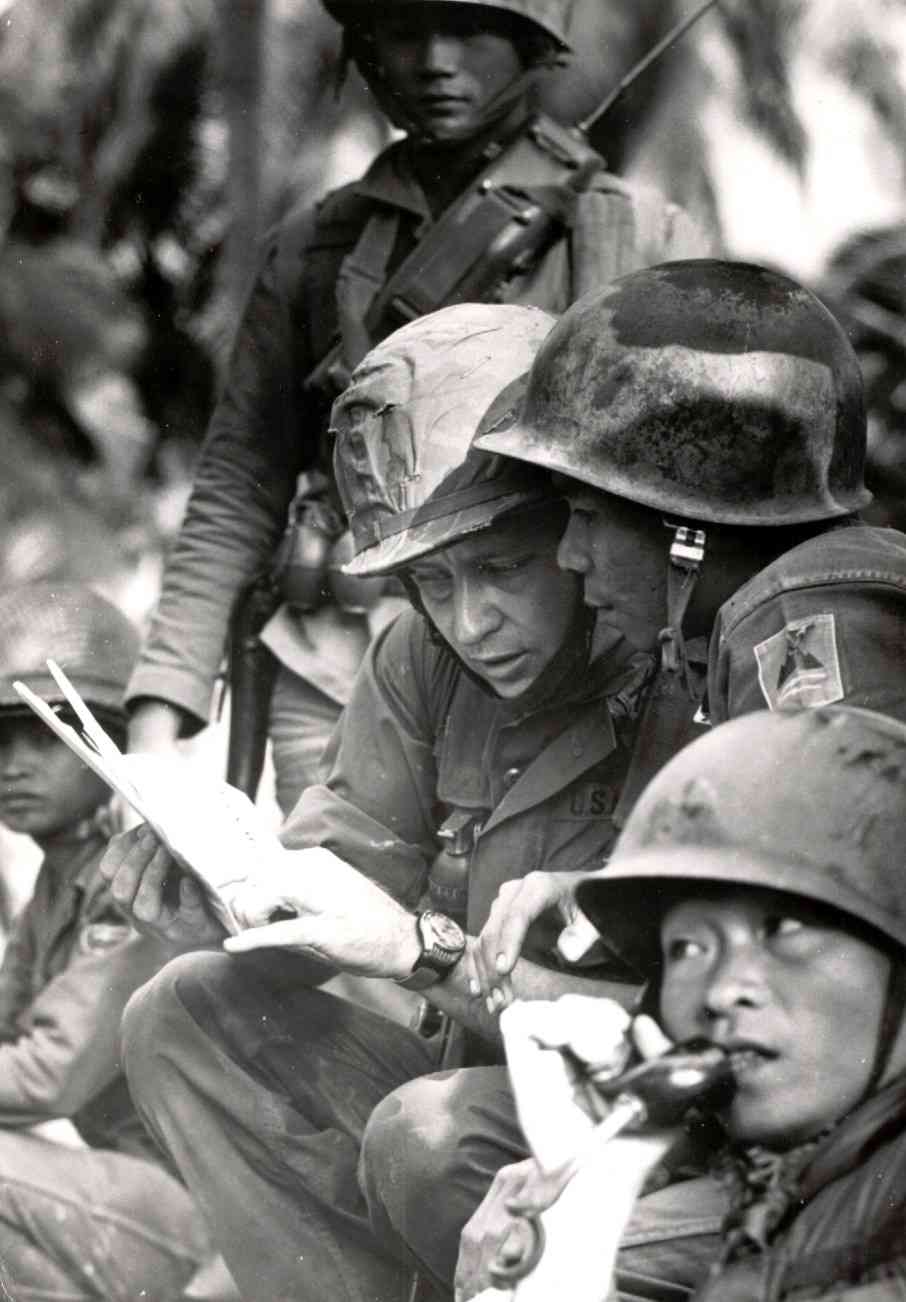

The conference on the Vietnam War at the College of William and Mary. Left to Right - Zalin Grant, Peter Arnett, Wallace Terry and Joseph

L. Galloway. I've known the three for 35 years. All of them are journalists

and authors--and were extraordinarily brave war correspondents.

|

I was invited to participate in a conference at the College of William

and Mary, in Virginia, on the 25th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam

War.

After I returned home, I said to my wife Claude: "I finally feel

the war is over for me. Maybe now I can tell my personal story."

"What's that got to do with a letter from a French village?"

she asked.

"I wouldn't be here if it hadn't been for the war," I said.

"That's how I met you."

"You are right," she said. "Do it."

A few weeks before I attended the William and Mary conference, Frank McCulloch's

two daughters asked me--as they asked others who had worked with him--to write

an appreciation of their father, as a surprise for his 80th birthday.

Frank McCulloch started me on my journalism career in the Saigon bureau of

Time magazine in 1965. After he left Time, McCulloch, a former US Marine platoon

sergeant, held many high positions in journalism, including as managing editor

of the Sacramento Bee and the San Francisco Examiner.

AN APPRECIATION: Frank McCulloch

It doesn't surprise me that Frank McCulloch has turned 80. He has handled aging

like he has handled everything else in his life. He has simply looked at it

squarely in the face, and said, "OK, you want to challenge me, then I'm

ready."

Of course, Frank knows who will win. He is a total realist. But that attitude

defines Frank for the people who know and love him.

"I ain't giving up."

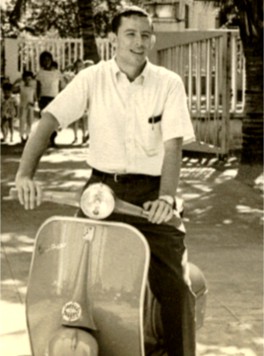

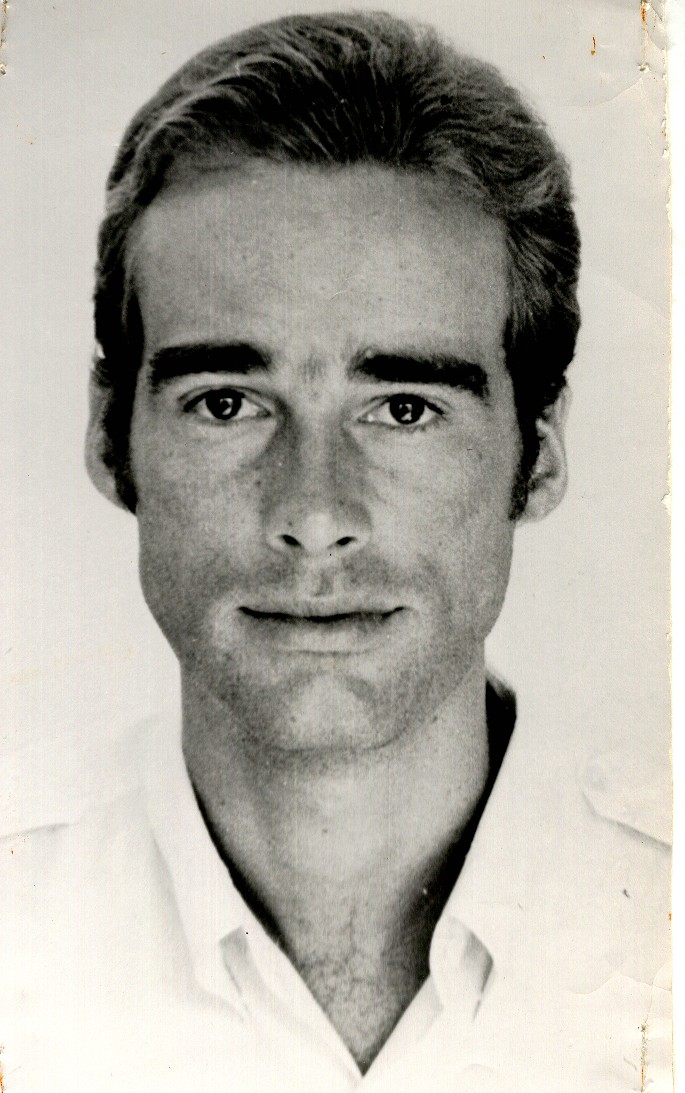

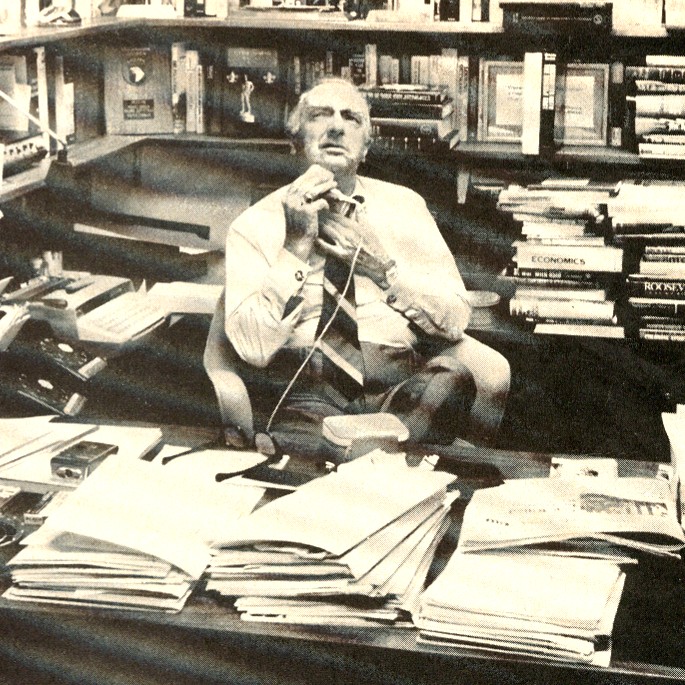

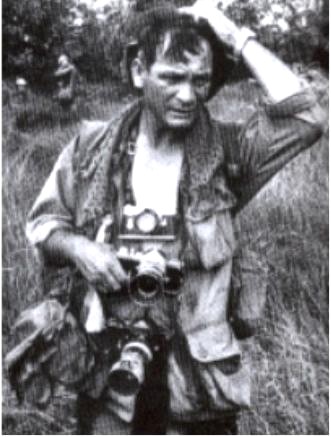

Frank McCulloch in Vietnam 1965. Tough and gentle, it's rare in a man.

McCulloch hired me in the Time magazine bureau after I completed my tour

as a US intelligence officer. He also hired Pham Xuan An, who turned out

to be a Viet Cong intelligence officer. Oops! |

As I say, I'm not surprised that Frank is turning 80. Actually, I'm surprised

by how old that makes me. But I know Frank understands that at this moment

of celebrating him, I'm thinking of myself. That's another thing that

defines Frank. Spare him the b.s.of life. He'll chuckle because he knows

I'm telling the truth. Only then can I say that I--we--love him, that

he has made our lives better in countless ways. For only when Frank knows

that you are speaking from the hard edge of truth, not the soft edge of

sentimentality, will he believe it.

I count it as one of the luckiest moments of my life when I met Frank

in Saigon in 1965, just before I was to be discharged from the Army Intelligence

Service. Actually we had met before, when he came to Danang to cover the

US Marines.

As weird as the idea seems to me today, I had established the US Army's

covert intelligence headquarters in Danang as a first lieutenant, which

was eventually used by the 525th MI Group. I took pride in that point

until I discovered, much later, that I had rented the villa from a member

of the Central Committee of the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong).

I had been a journalist for my college paper and a stringer for the Associated

Press, and Frank decided to take me on for Time. He was confronted with a war

that was heating up to the point of overwhelming his bureau's resources. I suppose

he thought I would make the suitable journalistic equivalent of cannon fodder.

No, I don't really think he thought that. On the other hand, he never encouraged

me to attend any embassy cocktail parties.

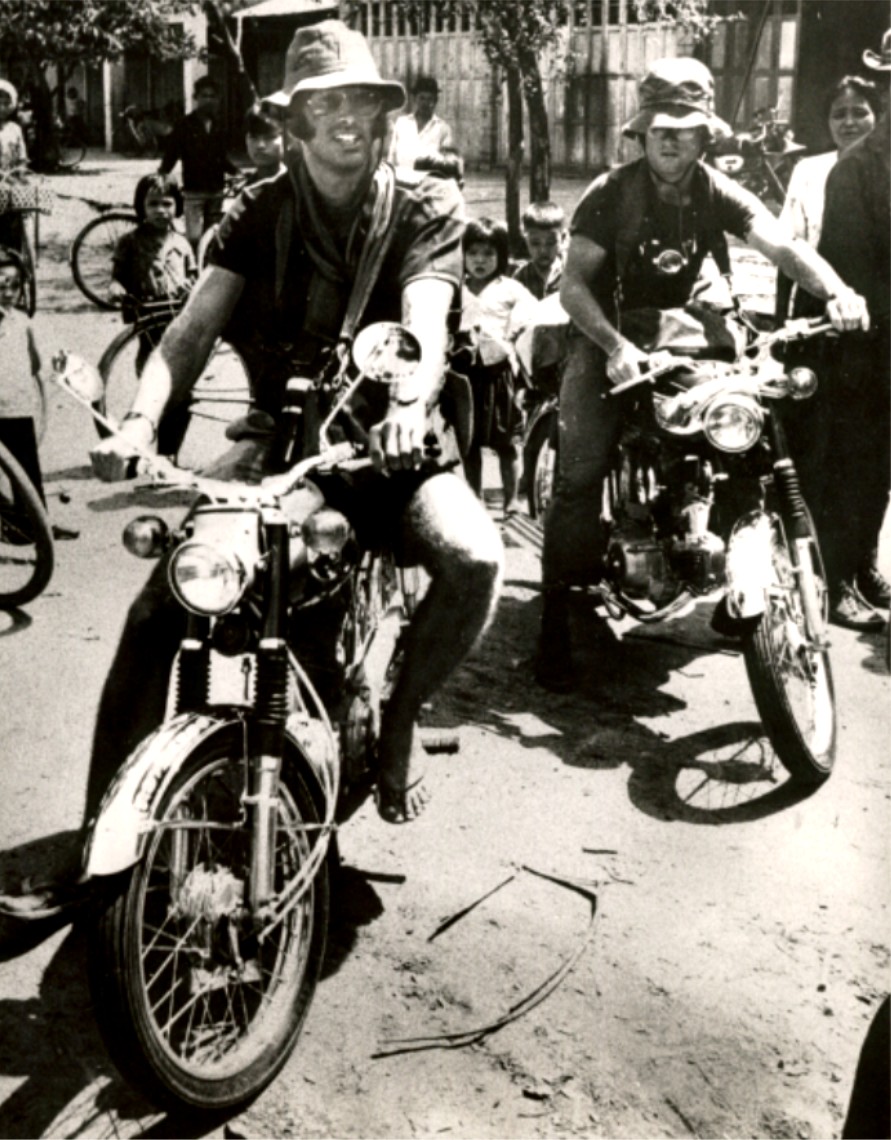

Danang 1965, when I met Frank McCulloch. I established

the Army's covert intelligence headquarters which was used for the rest

of the war, though I didn't know I was renting the villa from the NLF. The

kids behind me probably saved my life. I often took them on Sunday to China

Beach, and was lifeguard as they played in the sea, which their VC parents

obviously appreciated. |

That was another thing that defined Frank. He had an uncanny ability

to understand the talents of people and how they would fit into the larger

scheme of what he was trying to do. He knew that I would not be any good

at making small talk with diplomats, but that I would be fairly proficient

at elbowing my way onto a C-130 or a helicopter to get to the story.

But did he say this? No, Frank never said much about the mechanics of

journalism, the how-to's. He sat me down one time and drew a diagram to

show me how to develop and write a Time magazine story. Even better, he

told me how to deal with the editors at the New York headquarters, how

to propose a story or reply to their queries.

"Phrase it so they'll have to give you either a 'yes' or a 'no'

and nothing in between," he said. Good advice that stands today.

While he never said much or issued directives, Frank was always ready

to stop what he was doing to listen. I blush to think of the many times

that I, needing a little reassurance, stopped Frank as he was typing his

own file with machine-gun speed.

He would shift the toothpick in his mouth, wrap his hands around the back of

his head, lean back, and cheerfully act as though he was totally pleased to

be interrupted, in order to listen to a reporter's banalities or to answer an

obvious question. Frank was one of the most patient men I've ever known.

He was also one of the bravest. Frank didn't want to be a general or a colonel--he

was a born platoon leader. He loved nothing better than to get into the field

where the action was. And we loved being members of his platoon. We worked hard.

And we played hard--but I'd better not get into that, I'll let sweet memories

lie.

Of course we all knew there was a general in Frank's family--and her

name is Jakie. It's a helluva lot easier to jump out of a helicopter and risk

your life than to face the enormity of moving a household from place to place.

Not to mention raising children with an often absentee father.

Jakie McCulloch on the roof of the Carvavelle Hotel overlooking

the Saigon River. As my wife Claude said, "Jakie makes it work." Journalism

is hard on wives. If awards were given, hers would be the Medal of Honor. |

I've mentioned a few things that I think "defined" Frank. But

I haven't come to the heart of the mystery. Throughout his career, Frank

has attracted and bound to him some of the toughest and best journalists

in America. They are fiercely independent guys who believe that being

called "one of McCulloch's boys" was the highest honor they

could receive.

How did Frank do this? How did he stir such loyalty and love in the hard

and skeptical hearts of of so many reporters?

I can pose the question. But I can't answer it. And maybe it shouldn't

be answered. We journalists try to chop and slice too many things. Let's

just call it the magic of Frank McCulloch.

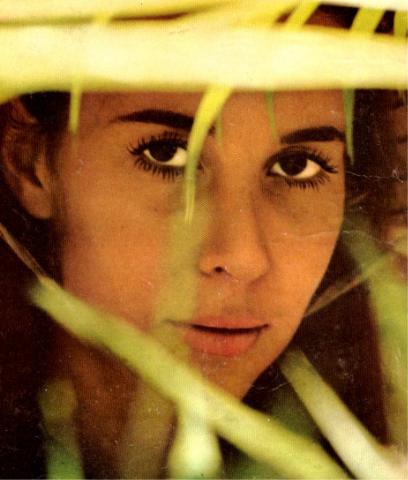

FIRST CAPTURED: Michèle Ray

Michèle Ray was the first journalist to be captured in Vietnam, and

that set off the random chain of events that brought me to live in a village

in the heart of France. Actually, I could probably say that I started it all,

since I was largely responsible for encouraging Michèle to do the thing

that got her captured.

Michèle arrived in Vietnam in 1966. She was a former Chanel model who

had made a name for herself in France by driving from the tip of South America

to Alaska, along with three other pretty young women. Her boyfriend was then

an unknown assistant film director who had caught the eye of an older actress.

When Michèle, 27, discovered that the assistant director had become

more than just the protégé of the actress (women sometimes "stumble

upon" a guy's letters), she fled to an adventure in Saigon, carrying a

handheld movie camera. I met her soon after she arrived. We fell into a deep

wartime romance.

Michèle was soft-spoken, with a ready smile, a woman who downplayed

her beauty. She didn't smoke or drink or do drugs. She wasn't much of a cook,

and didn't have a lot of formal education, but she was naturally smart, endowed

with a great deal of charm--and very brave.

I can't say that Michèle wasn't a journalist. Anybody can claim the

title. But of course she wasn't. She was an adventurer in the purest sense,

yet not a publicity seeker. I knew she was looking for something to do in Vietnam

that would fit her, so I suggested that she make a sort of modified Patagonia-to-Alaska

trip by driving from one end of South Vietnam to the other and filming a documentary

of her trip.

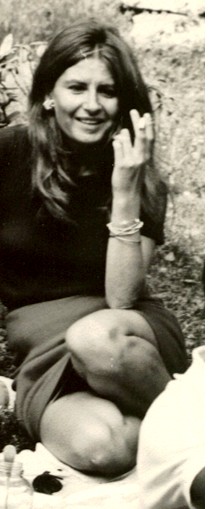

Michèle Ray, 27, was a former Chanel model and

a card-carrying journalist in Saigon. But actually she was an adventurer

of the purest kind. (Photo by Dick Swanson for Life) |

"Do you think I can?" she asked.

"The Americans are claiming all the roads in the country are now

open, at least in the daytime. I'll check with the officials and see what

they say."

And I did. They told me, yes, her trip seemed doable, if she followed

US military convoys at the dangerous places. So Michèle talked

the Renault company into giving her a little white Dauphine, and set off

to travel from the Mekong Delta in the south to the DMZ above Hue in the

north.

She made it a little more than halfway to the DMZ, when she came to a

place in the road that had been trenched so deeply by the Viet Cong that

it was impossible to get across.

Disappointed, she arranged with the US military to fly her and the car to the

closest place where the road was passable. Before the plane arrived, she decided

to drive to the trenched spot and film the place, to show in her documentary

that it was impossible to cross.

When she got to the spot, she had the first flat tire of her trip. While she

was trying to fix it, she was captured by the Viet Cong. Naturally, I felt somewhat

responsible, having encouraged her to make the drive. So I rushed to the place

where she had disappeared.

Luckily, the American commander in the area was Colonel George Casey of the

First Cavalry Division, an old friend. Colonel Casey knew that I had been trained

as both an infantry and intelligence officer and that I spoke Vietnamese, so

he told me to gather all the info I could on her disappearance and he would

provide me with the helicopters if I could talk the local Vietnamese commander

into providing the troops.

On Saturday morning, January 21, 1967, I led the eight helicopters George Casey

had assigned to the operation to a soccer field where we were to pick up the

Vietnamese troops. I jumped out and ran over to greet the American adviser.

We both stopped in our tracks and gaped at each other. The adviser was Captain

Robert Fraley, of Florence SC, my college classmate and old friend.

"What are you doing here?" Bob shouted over the noise of the helicopter

blades.

"I'm looking for my French girlfriend," I shouted back.

"Let's go!" he said.

This was the first Bob had heard of the operation. He thought it was going

to be a routine sweep.

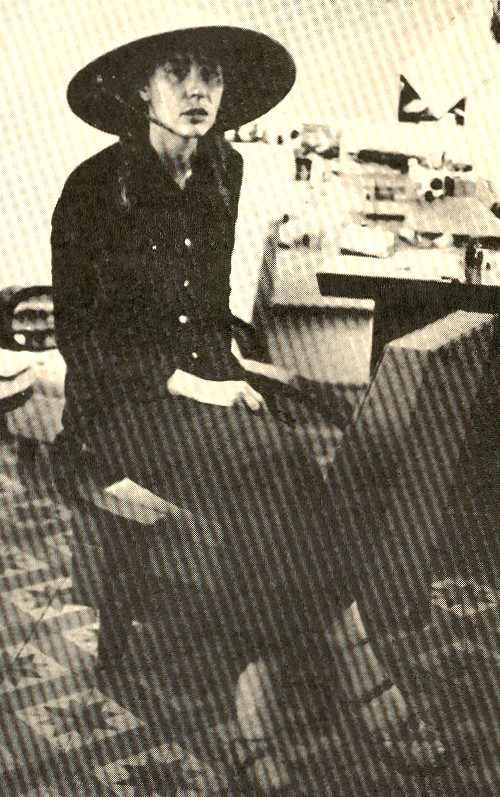

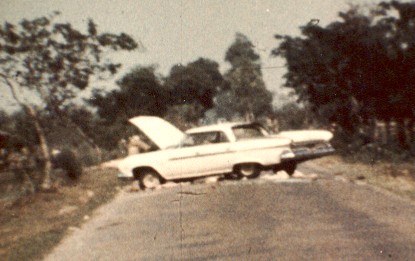

Michèle at the time she was captured. She gave

the gold chain she is wearing around her neck to the Viet Cong, as appreciation

for her good treatment. She became sympathetic to their cause. |

And we were off for a helicopter assault on a rice paddy. Viet Cong bullets

pocked the water around us as we jumped out. I was relieved to hear the

sound of American M-79 rifle grenades being fired--until I realized they

were being fired at us, arms the Viet Cong had taken off dead Americans.

But the helicopters hosed down the tree-line with rocket and machine-gun

fire, and we were able to outflank the guerrillas, suffering no friendly

casualties.

We found Michèle's car exactly where my informants had told me

it would be. The Renault was completely covered with palm fronds, in a

field near a river.

In my haste to see if Michèle had perhaps left a note, I uncovered

only half the car and started to open the door, my hand was on the handle.

A Vietnamese soldier standing behind me grabbed my hand and jerked it

away.

"Why don't you uncover the whole car first?" he said.

I did. He pointed to a white kitchen string that was attached to the door.

I looked under the car. The string led to an American grenade. The military

safety pin had been removed and replaced by a normal safety pin, the store-bought

kind. The safety pin was stuck through the hole, keeping the grenade from going

off, but it was open, not clasped. Next to the grenade was an unexploded 155mm

US howitzer shell.

Open the door, the string pulls the safety pin out, the grenade goes off and

the 155mm shell explodes, blowing me and the car sky-high.

I got up and looked at the Vietnamese soldier. He smiled slightly. Then walked

away.

I talked to the rice farmers who lived in thatched huts in the area. I told

them Michèle was a French journalist--not an American spy, as I knew

they would believe. They told me the Viet Cong had moved her into the mountains

the night before.

I radioed Casey's staff and asked them to send a big Chinook helicopter to

lift out Michèle's car. After waiting for two hours, I suddenly realized

they weren't going to take any more risks for me. And I couldn't blame them.

The keys were missing and the Renault's steering wheel was locked. Bob Fraley

and his Vietnamese counterpart, who was one of the best company-grade officers

I'd ever met (and I'd met a lot), positioned the troops around the car.

I'm looking under Michèle's car at the most frightening

boobytrap I'd ever seen. I should have crawled over on my knees and thanked

that Vietnamese soldier for saving my life. |

Then we pushed and dragged the car through three miles of Viet Cong territory,

frequently being shot at by VC snipers.

We got it to an airstrip, and I later arranged to have the car flown

to Saigon, where I returned it to the Renault company.

Does this sound crazy to you?

Well, it didn't to me then. But it sure does now.

Michèle came to the Time bureau, looking for me,

as soon as she was released. We left for a holiday in Hong Kong and then

Rome, where she worked on a book about her experiences. It's called "The

Two Shores of Hell," and was published in French and English. |

Michèle was released a few days later. She had heard I'd been

looking for her. She thought it had helped bring about her release. And

of course she was pleased.

The Viet Cong had treated Michèle well, and she was converted

to their cause. Whereas the only thing the Americans seemed interested

in was asking whether she had been raped.

After more adventures, including recovering Che Guevara's diary in Bolivia

and giving it to Fidel Castro (she asked me to help but I declined), Michèle

eventually married film director Costa-Gavras, whom she'd known earlier,

and later became a movie producer.

My friend Colonel George Casey became a general and the commander of

the First Cavalry Division. He was killed in a helicopter crash near the

end of the war. My college classmate Bob Fraley survived the war and became

a ROTC instructor.

When I asked him, years later, what was the most unusual thing that happened

to him during the war, he said, "Are you kidding?"

WERE THE NEWSMEN DEAD OR ALIVE?

At the William & Mary conference, Joseph Galloway, who was a UPI reporter

in Saigon, put his finger on the reason that Wallace Terry and I went on a two-man

operation that almost got us killed.

"I didn't trust the guy who told the story," Joe said to me, over

hamburgers during a break at the conference.

"I didn't either," I said. "And that's why we wound up in Cholon

among the Viet Cong."

It was Sunday morning, May 5, 1968. The Viet Cong and North Vietnamese had

invaded Saigon once again, as they'd done four months earlier during the Tet

Offensive. They were concentrated in the Chinese quarter, known as Cholon.

Janice Terry phoned me at the Continental Hotel, where I was staying after

recently returning to Saigon from Washington as The New Republic's correspondent.

Her husband, Wallace Terry, was a Time magazine reporter whom I had worked with

in Washington.

"Wally needs you," Janice said.

"Where is he?"

"At the Time villa."

I rushed to the villa, which was several blocks away, and found Wally Terry

pouring a cup of scotch for a freelance journalist I didn't really know but

had seen around town--an Australian, I think. The guy was trembling and obviously

traumatized.

Left to Right - John Cantwell, Ronald Laramy, Michael Birch, Bruce Piggot. A freelancer who was with them said they had all been killed

in Saigon's Chinese quarter on May 5, 1968--ambushed by a Viet Cong squad. But were they all dead? John Cantwell had replaced me in Time's Saigon bureau and was a close friend of Wallace Terry. We set out to find them. |

"Listen," Wally said. "Tell it again, this time to Zalin."

"They are all dead," the freelancer said.

He had hooked up with Time's John Cantwell that morning and, along with three

other journalists--Ronald Laramy (British) and two Australians, Michael Birch

and Bruce Piggot--they had driven into Cholon against the flow of refugees and

run into a Viet Cong squad, which had sprayed their jeep with AK-47 fire. The

guy said he had jumped out when they stopped and run zigzagging away and escaped.

I looked at Wally. He knew what I was thinking. The freelancer's story didn't

ring completely true to me. Of course I believed he had been with Cantwell and

the journalists. But if they had run into a VC squad and been sprayed with AK

fire from close range it was unlikely that he would have escaped. He could have.

Quite possibly, though, he had bailed out when he first saw the armed guerrillas

ahead.

That led to a question: Was he really sure the newsmen were all dead? How about

if one or two were only wounded and lying in Cholon bleeding to death as we

spoke?

John Cantwell had replaced me in Time's Saigon bureau. He had become a particularly

close friend of Wally Terry who, as acting bureau chief, had agreed with Cantwell's

suggestion that he drive around town to find out what was going on. Cantwell

reasoned that it was better for him to do it, since Wally's wife Janice had

just arrived from Singapore, where she lived with their three children, to spend

a few days with her husband.

We got on the phone to the US military headquarters, and tried to find out

if any American units were moving into the area where the journalists were missing.

They were. But when we caught up with them, we saw that a tank had thrown a

track and would be blocking traffic into Cholon from that direction for the

next few hours.

We decided to go it alone. A Chinese photographer, who knew Cholon well, drove

us in a Mini-Moke, a French jeep like the one Cantwell had been driving. The

main streets of Cholon were deserted and eerily quiet. The photographer suddenly

said he was feeling sick to his stomach and couldn't drive us any farther.

I wasn't feeling so great myself, my stomach was churning too, and I understood

his fear. So I told him to drop us off at a nearby Vietnamese police precinct.

There, we found the precinct commander, a lieutenant colonel, just sitting down

to an elaborate breakfast. He was dressed in full battle gear, including flak

jacket. As Wally Terry later wrote in a magazine article, I lost my "cool."

Here he was preparing to tuck into a leisurely breakfast, while his precinct

was being overrun by the Viet Cong. And--more to our point--while Cantwell and

the others could have been bleeding to death. After I yelled a few epithets

in Vietnamese and English at him, the colonel decided to forego his breakfast--and

calmly, almost cheerfully, agreed to drive us in an armored convoy to where

the newsmen had last been seen.

This is what we saw when we finally reached the newsmen. John

Cantwell, bloated in the heat and covered with flies, had been shot 17

times. The guy in the back of the jeep was actually sitting up straight,

hands held high in in surrender.

|

We got no closer than four blocks to the turnoff the journalists had

taken. The lieutenant colonel stopped the convoy, pulled a pump shotgun

from underneath the dash of his jeep, and said: This is too dangerous.

You can have my gun. And good luck."

I flagged down a taxi, a little yellow and blue Renault, and offered

the driver ten dollars for every block he would drive us, a king's ransom

for him. He drove us two blocks into the sound of automatic fire. He stopped

and waved us out of the cab. "No amount of money is worth this."

Wally and I started walking down the street alone. Vietnamese paratroopers

were standing in the doorways, but were not moving. They smiled at us when we

passed them, as if they knew a secret.

"This is impossible," I said to Wally. "The VC are everywhere.

It would be suicidal."

We turned back.

We went to pick up Wally's wife, Janice, and then we had a hardly-touched lunch

at a French restaurant in the center of Saigon, while we waited for US units

to move closer to the area where the newsmen were. At three p.m. we returned

to Cholon and I talked to some refugees that I found from the newsmen's area.

They told me they thought all the white men were dead. But Wally and I were

still hoping against hope.

The Americans were pushing into the area. We were able to get to the beginning

of the small dirt road where Cantwell had turned off. We saw an American demolition

team (bomb squad) nearby. They told us it was too dangerous to go farther. When

we told them we were going to try anyway, they handed us a couple of rifles,

and we headed down the dirt road. There, we found them.

Ron Laramy was sitting up, in backseat of the jeep, his arms still raised.

The others were on the ground. Full of holes. Bodies caked with blood. Bloated

from the heat. Cantwell had been shot 17 times.

Wally started to touch them, but I waved him off. I was thinking about how

close I had come to getting blown up by Michèle's boobytrapped car. We

walked back to try to persuade the demolition team to come with us to check

for boobytraps.

Left to Right - Zalin Grant and Wallace Terry on May 5, 1968. Wally and

I loaded the bodies in the jeep and then quickly drove outside the danger

zone. |

The demolition team has called an ambulance, but the driver refuses to

come closer. We are going to have to bring the bodies out ourselves.

The demolition team finally agrees to drive us back in. But when we get

there, they keep a safe distance. Only a black sergeant volunteers to

check for boobytraps.

After he finishes, Wally and I begin to load the bodies.

Suddenly, nearly 30 young men dressed in the black pajamas of guerrillas come

dogtrotting past us in formation. They are clearly Viet Cong who are trying

to escape before the Americans move in with their tanks and armored cars. They

look at us with pure hatred.

"Let's get the hell out of here," I tell Wally. "Before we get

it too."

Later, after the depression of Cantwell's death lifted, I thought of that day.

What we'd tried to do had proved futile. But it made more sense to me than anything

I'd ever done.

SEAN & DANA: Two Friends Missing in Cambodia

On April 6, 1970, Sean Flynn and Dana Stone disappeared on motorcycles in Cambodia.

The news bulletin contained little hard information. It said they were captured

by the Viet Cong at a highway checkpoint near the Vietnam border.

For the past year, Dana Stone and I had driven identical cream-colored Volkswagen

campers overland from Singapore to Europe. He and his wife Louise Smizer, and

Susan Harrigan and I, had lived in a Singapore hotel together as we prepared

for the trip, but split up to take separate routes when we started out, keeping

in touch by dropping off notes at US embassies along the way. Dana and Louise

were always on the road a few days ahead of us.

One night Susan and I camped half way to Katmandu, next to a precipice. The

overpowering beauty of Annapurna and Mount Everest rose to the front of us.

Next morning I awoke with a start. Our van was being pushed and shaken by someone

outside. I was sure we were being rolled into the gorge by thieves, we were

dead.

No, it was just Dana--stopping to say hello. They were headed out of Nepal

back to India.

Dana Stone, a college dropout from rural Vermont, had been a lumberjack, gold prospector, male model, and sailor before arriving in Saigon at age 27 to try his hand at war photography. He was one of the best. |

A wiry five-six redhead who wore thick hornrims, Dana was propelled by

such nervous energy that it seemed to trail him like a whiff of steam.

He could seldom sit still for more than five minutes.

Dana was the Saigon press corps's inexhaustible practical joker--forever

tying shoelaces together, short-sheeting beds, or running breathless into

the Danang Press Center to report an imaginary enemy attack that would

send reporters scrambling for their jeeps.

Dana intended to drive his VW camper to Sweden and find a job as a lumberjack.

But it didn't work out. After spending time in Asia, he hated the cold.

A note was waiting for me when I got to Paris. As usual with Dana it had no

beginning or end. It just said that he had decided to return to Vietnam.

I wrote him a quick letter. I urged him not to go back.

"You have already used up too much luck," I said. Knowing that his

decision was already made, I added a PS: "Keep your head down."

Sean Flynn and Dana Stone were opposites in almost every way, except for their

common courage and their dislike for pretentiousness and predictability. At

six-two, blond-haired, with hazel-green eyes, Sean was even more handsome than

his late movie-actor father. Being singled out as the son of Errol Flynn all

his life had left him with a reserve that people who didn't know him confused

with standoffishness. In reality, Sean was shy and almost European-formal in

his manners. (His mother, actress Lili Damita, was the French bombshell of her

time but a very caring mother, as I learned when I got to know her.) He spoke

quietly and enunciated his words with care--he'd taken voice lessons as an actor--

while Dana, his anti-intellectual pose intact, talked in machine-gun bursts

of slurred consonants and clipped vowels.

Sean Flynn, circa 1968. I met Sean only a day or so after

he arrived in Vietnam and we became friends.We were the same age. Shy with

women, he liked Michèle Ray and the operation I ran to find her. |

Sean had dropped out of Duke as a freshman and made a number of low-budget

adventure films. Sometimes Vietnamese kids would run up and ask him for

his autograph during a firefight.

"Suppose you'd received worldwide acclaim for your acting ability

after your first film," I asked him one day. "What would have

happened then?"

"It's hard to say," he replied. "I won't say I wasn't

interested in making films. But I always felt--I don't mind fighting my

father. But I realized that I was fighting him on his own turf. It came

down to that."

The way Sean chose to fight his father eventually got him killed.

Shortly after Dana Stone returned to Saigon, Sean appeared too. He had

been living in Bali. Sean had come back, he told friends, for the purpose

of closing down his Tu Do Street apartment. He had decided to make a clean

break with the past and withdraw to Bali, where he would live as a beachcomber.

Sean and Dana's return to Saigon coincided with the upheaval in Cambodia. Prince

Norodom Sihanouk was overthrown by a rightist general by the name of Lon Nol.

Sihanouk's façade of neutrality was crumbling. After years of avoiding

it, Cambodia was finally being dragged into the Vietnam War.

Flynn was tempted to take one last assignment. He dropped by to talk to Marsh

Clark, the Time bureau chief. The two were friends. Sean told Marsh he was interested

in going to Cambodia. Clark said he needed a photographer to cover the fighting

there. They made a deal, and Sean left the next day. In Phnom Penh, Sean discovered

that Dana had returned as a cameraman for CBS. It was like old times.

Sean and Dana headed toward the Vietnam border, where the fighting was taking

place, on two red motorcycles. Sean was a childhood friend of Peter Fonda, the

star of "Easy Rider," and later much was made out of the connection.

On Monday morning, April 6, 1970, Sean and Dana motored past a seemingly deserted

VC checkpoint just east of the village of Chi Pou, which had been overrun and

destroyed several nights before. At noon a press tour arrived in Chi Pou. Prodded

by American reporters in Phnom Penh, the government information office had arranged

for eight French armored cars and a Cambodian troop detachment of 200 men to

ride shotgun for a caravan of newsmen.

Sean Flynn (left) and Dana Stone, less than two hours

before they were captured. Sean and Dana were having bantering mock-argument

in front of other newsmen about what they should do. "Flynn just wants me

to go up there and get caught," Dana said. "After two years in Vietnam I'm

not about to get zapped here." |

|

Three newsmen left the armed escort for the government press tour to drive alone down the road toward the border. They were captured at a VC checkpoint. Flynn and Stone followed

after them, and this is what they saw when they arrived.

|

The newsmen soon tired of poking in the ruins. Several wandered away. Soon

there were rumors that three reporters were missing from the press tour and

had been captured at the checkpoint--two Japanese TV reporters and a French

photographer.The VC pulled their white Dodge across the road in a blocking position,

and returned to a hiding place in the woods.

When Sean and Dana saw the car from a distance, they stopped and sat a few

minutes on their Hondas, trying to make up their minds what to do. When word

came of trouble at the checkpoint, the Cambodian troop commander ordered the

entire escort force to return to the safety of the nearest provincial capital.

Sean and Dana were alone.

At three p.m., a French TV team headed toward the checkpoint by car. One of

them turned on his camera as Flynn cycled toward them, warning, "Pathet

Lao! Pathet Lao!" It was a measure of his excitement that he confused the

guerrillas of Cambodia with those of Laos.

Dana Stone was not in sight. The French TV team turned back. Sean Flynn did

not.

Two days later more newsmen were captured at the checkpoint, and others began

to disappear nearby.

By mid-April 1970, eleven journalists and two French teachers had been taken

by the guerrillas. The press corps was shocked.

Many people, however, believed the newsmen would soon be released. The adventure

of Michèle Ray was on everybody's mind. Sean Flynn had talked to me admiringly

many times about how Michèle had gotten away with it.

The Viet Cong didn't hold journalists. Or so a lot of people thought.

I was in Paris, having just sold my camper, and Time's bureau chief suggested

that I draft a memo for New York headquarters suggesting a few steps that should

be taken to help Sean and Dana. After Wally Terry and I had recovered the newsmen's

bodies in Cholon, Time had made a flattering effort to rehire me. I had turned

them down, but my relations with the magazine remained warm, and the Saigon

bureau chief, Marsh Clark, was a special friend.

The next day Time's chief of correspondents telephoned me in Paris and asked

if I would return to Saigon as soon as possible, to pull together the facts

of what had happened. I refused to accept any payment for my work, but it was

understood that the magazine would cover my expenses. CBS later joined with

Time to sponsor my trip.

On April 19, 1970, Marsh Clark met me at the Saigon airport.

"I'm really glad to see you," he said.

"I'm not sure I can be of any help," I said. I was already beginning

to feel that I had overcommitted myself.

"Anything you can do will be a help." At lunch, Marsh was very troubled.

"I just feel terrible about the whole thing."

"It's not your fault," I said. "Sean and Dana knew the score

as well as anyone."

"I know but I wish there was something I could do. What do you have in

mind?"

"Well, first I'd like to get in touch with the key American and Vietnamese

officials to tell them what I'm up to. I don't want to try to move around without

establishing the proper coordination. Maybe I can get some help from the Vietnamese

intelligence people. Then I'll start to pull together the story."

President Nguyen Van Thieu of the Saigon government ordered his intelligence

chief to assign his best intelligence officer to work with me. Tong was in his

early thirties and had been trained by the CIA at a secret base on the island

of Saipan. He was in charge of the CIA's safehouses in Saigon, and ran whatever

sensitive operations the CIA and his Vietnamese chief, Colonel Binh, assigned

him.

"Colonel Binh says Mr. Shackley is furious that I have been assigned to

work with you," Tong told me. Mr. Shackley was Theodore (Ted) Shackley,

the CIA station chief in Saigon. As Tong recounted the details of the conversation

he'd had with Colonel Binh, I realized that the CIA had a wire tap in President

Thieu's office. That was the only way Shackley could have known the details

of the conversation Marsh Clark and I had with Thieu's nephew and assistant,

Hoang Duc Nha.

"Don't worry, Tong," I said. "We Americans have an expression

that goes like this: Ted Shackley can kiss my ass."

But Tong knew we were headed for trouble. And so did I. It came the next day

when Tong and I started work at the Tay Ninh amnesty center, talking to Viet

Cong who had surrendered. One of Shackley's minions came roaring up and ordered

us out of the Vietnamese installation. We almost came to blows, but I caught

myself, and told him I was with Tong, who quickly showed him his orders from

Vietnamese Central Intelligence. The orders were in Vietnamese and the American

couldn't speak or read the language. He started to harangue Tong. I stepped

in and told him I had cleared this operation with William Colby, the CIA man

who was in charge of the whole US bureaucracy, and that I would have him fired.

He didn't believe me, and said that he would file a report against me with Colby.

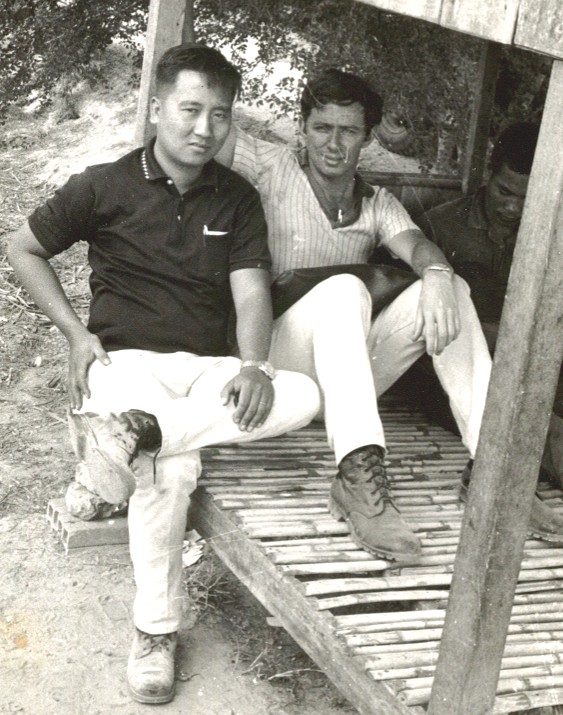

Tong (left) and I on the trail of the missing journalists

in Cambodia, 1970. Tong was an excellent intelligence officer, polite and

soft-spoken to everyone. An Air Vietnam flight bag with two M-3 submachine

guns inside was never out of his reach. |

Which he did.

I had known Colby for years and had in fact cleared what we were doing

with him. Colby sent a memo to everyone that was so artful in its bureaucratese

that it made me laugh. We had no further trouble with the CIA or anyone

else. Tong was pretty impressed.

Tong was the best Vietnamese intelligence officer I'd ever known. During

the Tet Offensive, he had rushed home to rescue his family, and had to

escape the fire of the Americans and the Viet Cong, both of whom thought

he was the enemy.

He would speak so softly and politely to the Viet Cong we interviewed

that they would lean toward him, anxious to hear what he was saying. And

then they would tell us everything they knew.

We sometimes split up and did separate interviews. But we found we were more

effective if he asked the questions while I listened and made the decision whether

to pursue the interview further. It was the time of the American invasion of

Cambodia and hundreds of Viet Cong were being cornered into surrendering. We

soon had a handle on the Viet Cong/Khmer Rouge organization in the border area

where the newsmen were captured.

It was not our mission, and I tried to steer away from it, but we sometimes

came across important information about US military prisoners of war. Once I

interviewed a Viet Cong who had already been interrogated by US military intelligence

agents but they had failed to ask him about "Bright Light" (POW) information,

and he knew the exact location of a POW camp. It was a Saturday night and I

pulled the military's chief public information officer out the officers' club

and gave him my report. The US Special Forces commandos cranked up an operation

and found the camp but the American POWs had been moved. They passed their thanks

to Tong and me.

Within two months I could confidently write a report for Time and CBS detailing

how and when the newsmen were captured and most importantly, by whom. They were

still in Cambodia but in the hands of the North Vietnamese. I considered my

mission at an end, and returned to the Washington to work for The New Republic.

I quickly discovered, though, that I had become the focal point for information

on the missing newsmen. Even Japanese, French and German organizations were

contacting me, and it interfered with my work as a journalist. Somebody suggested

that a committee be established to coordinate international efforts to free

the newsmen. John Laurence, a CBS reporter and friend of Sean and Dana, recruited

Walter Cronkite to serve as chairman. The other members quickly fell into place:Tom

Wicker, Treasurer; Peter Arnett, Secretary; and Barry Bingham Sr, Otis Chandler,

Richard Dudman, Osborn Elliott, Murray J. Gart, Katherine Graham, David Halberstam,

Ward Just, Frank McCulloch.

Walter Cronkite shaving in his CBS office. While I worked with Cronkite on the missing journalists, I kept looking for a chink in his armor as "the most trusted person in America." But I didn't find it. He was a standup guy, and I finally figured it out. He was an ex-war correspondent himself. |

I expected Walter Cronkite to be only semi-involved in the committee's

work, sort of a celebrity figurehead. But from the beginning, he was ready

to devote his time and energy to the issue.

I met with him numerous times at his New York office, and he eventually

set up a meeting with Henry Kissinger at the White House, so that we could

ask him to work through the Chinese to try to free the newsmen. Other

committee members also were ready to pitch in.

As in the case with Time, I did not accept any compensation for my work,

but Cronkite and Bingham raised the money for the committee's expenses.

The journalists were not freed. And the story of what happened after the Cronkite

committee was established is much too complicated to relate here and will be

better told in a book I am writing. But I began this letter by saying that Vietnam

was the reason that I live in a French village, and now I am ready to explain.

When Tong and I were interviewing the Viet Cong in 1970, I came across a North

Vietnamese who said he had served as a guard at POW camp in North Vietnam where

American pilots were held. He also said he had met a French woman who was being

held by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, only a few days before. The information

about the POW camp was much too serious for Tong and me to handle. So I advised

the chief of the Tay Ninh amnesty center to alert the CIA or Military Intelligence

about this source. And indeed, he turned out to be the source for the US raid

on the Son Tay POW camp. But I identified the source in May and the operation

wasn't conducted until November. Not surprising, the American POWs had been

moved.

The other information--about the captured French woman--I discounted. I had

not heard of any French woman being captured in Cambodia. But several days later

she showed up in Saigon. She was in Indochina to write a series of articles

for a French medical magazine on hospital care in the war zone, and was in Cambodia

at the time of the American invasion. When she tried to take refuge at a French

rubber plantation, she was captured on the road by the Khmer Rouge. One of the

very few lucky journalists, she had been released after a week.

Claude was her name.

Claude (upper left, facing away) with the Khmer Rouge

in Cambodia shortly before they released her. She lost weight fast. The

armed guard to her right never let her out of his sight. |

|

Claude with the Khmer Rouge April 1970. Why did they release

her after only a week? Maybe because she was captured near Viet Cong/Khmer

Rouge headquarters and they were able to make a quick decision. |

I invited Claude to lunch, to talk about her experiences, and to see if she

had heard about any other journalists during her captivity. To keep it simple,

we both ordered steak frites.

When the french fries arrived, Claude took one look at them and said, "I'm

not eating this. Waiter!"

"Shh," I said. "This is a war zone. One has to make compensations."

"If they have potatoes and cooking oil there is no reason they can't make

decent frites," Claude said. "These were cooked in oil that has been

used a hundred times. You Americans have no standards."

She asked the waiter to tell the chef to try again, this time with fresh cooking

oil. Needless to say, it was the best meal I had in Saigon during that period.

After recovering her health from the trauma of captivity, Claude looked like this. It must have been the steak frites. |

And that was the start of what has been thirty years and still counting.

Still counting, too, the hundreds of times I've heard the same thing I

heard that first day about "maintaining standards" when it comes

to cooking and cuisine.

Yes, I know, this sounds a little weird, doesn't it? Not only another

French woman. But another captured French woman? Only four women

journalists were captured during the Vietnam War, and two of them were

French.

Absolute coincidence.

Claude was brave and a world traveler but not an adventurer. A divorcée

with two sons (her ex-husband remains our good friend), she had attended

the University of Paris medical school. Her joys were cooking and books.

She liked nothing better than settling down to read Proust's À

la recherche du temps perdu for about the twentieth time.

While we lived in Spain for 12 years, the British writer Gerald Brenan

was our next-door neighbor and he gave Claude a tutorial in English and

American literature. I mention this because Claude recalls her tea-and-book

chat with the very erudite Brenan as one of the highlights of her life.

Of course the Vietnam War was always with us. And it was only at the

conference at William and Mary did it seem to come to an end.

THE CONFERENCE AT WILLIAM & MARY

There was a good run of names. Twenty or so panelists. But heavy on journalists--with

four Pulitzer-prize winners--who had actually been in Vietnam and light on academics,

who often populate such meetings. It was sponsored by the Vietnam Veterans of

America, and my old friend Wallace Terry was called upon to help organize it--did

a good job, too.

Peter Arnett and Joe Galloway and I got together one day for lunch. I hadn't

seen either one of them for a few years. Joe had lost his wife to cancer and

remarried in that period and was back working for US News and World Report.

Peter Arnett had been fired by CNN for a hoked-up story about the American use

of nerve gas in Laos. I thought Peter should have backed off from his claim

that he was not responsible because he didn't write the story, but I also thought

the whole mess was overblown and that he should have been reinstated. You don't

fire a guy a like that for making one error over the course of a career. But

if you're Ted Turner, I guess you do.

Otherwise, everything went relatively smoothly. On one panel, I attacked a

well-known journalist who casually slandered John Paul Vann. Vann was dead,

killed in a helicopter crash near war's end, but had he been there, he would

have had no qualms about kicking the journalist in the rear. A few people started

fluttering around when they thought I might be ready to act as a stand-in for

Vann. But everything quieted down. Guess who didn't get called on for the rest

of that panel?

I was impressed by how polished many of the journalists were at public speaking.

I'm pretty lousy myself, my best panel was a one-on-one with Everett Alvarez

Jr., the longest-held POW during the war. But some of them sounded like professional

speakers. I guess that's where journalism is headed these days. The reporting

and writing are getting worse, the speaking better.

William Conrad Gibbons (left) and I at the conference.William

Gibbons has created a magnificent four-volume (the 5th is coming) history

called "The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War."Bill's work is essential

to anyone who is seriously interested in learning how we got into the war

and what we did. I met Bill at the Library of Congress years ago and we've

developed a strong mutual admiration society. Great wife too--Pat. |

|

With Frederick Downs Jr, who was wounded for the fourth time as a platoon leader in 1968. He set off a "bouncing betty" mine--my worst nightmare--and lost his arm and various parts of his now bionic body. I knew his work but hadn't met Fred until the conference, and I tell you he's really a great guy. You ought to buy his books, especially "Aftermath: A Soldier's Return from Vietnam". |

I got the chance to talk to Lieutenant General (ret) Harold Moore at the conference.

He was Colonel Hal Moore of the First Cavalry Division when I first met him

in 1965 at the first major battle of the war, Ia Drang. I was there but he didn't

remember me, recalling instead my old boss, Frank McCulloch, whom he loved and

respected. When we started talking about the Michèle Ray operation, I

discovered that George Casey, the colonel who had given me the helicopters,

was one of Hal Moore's closest friends. Gen. Moore and Joe Galloway wrote a

best-selling book about the Ia Drang battle called "We Were Soldiers Once

and Young."

I spoke with other guys I hadn't seen for years, like Sydney Schanberg, who

was portrayed in the movie "The Killing Fields," and Philip Caputo,

who wrote "A Rumor of War" and other books. Since I'm winding the

Letter up, let me end with the run of names of the panelists: Everett Alvarez

Jr, Peter Arnett, Philip Caputo, Tom Corey, Edward P. Crapol, Frederick Downs

Jr, Patrick Sheane Duncan, John Michael Finn, Herbert Fix, Marsha Four, Joseph

L. Galloway, William Conrad Gibbons, James R. Golden, Zalin Grant, James E.

Griffin, Stanley Karnow, Marc Leepson, Harold G. Moore, Sydney Schanberg, Ronald

Spector, Wallace Terry, Rick Weidman.

The William and Mary conference ended at noon on Saturday, and a few

of us got together at an Italian restaurant outside Williamsberg. The staff

had us spotted from the first. They threw us the keys and left. We ate,

drank, and told war tales all afternoon. It felt like Saigon. That's Phil

Caputo prominently on the right and from left to right Joe Galloway, Fred

Downs, and Wally Terry. We don't quite look the way we used to. |

Well, the war was over for me. And I knew that I could finally go home again.

But where was home? No question. A village in the heart of France.

Claude was standing over me as I finished this. "People are going to think

you are crazy when they read this," she said. "And they don't know

the half of it."

"Crazy is as crazy does," I said.

UPDATE

Some time after I wrote this Letter, I discovered new material to add to my

stories. I waited until I had collected enough to justify writing this update

for new readers and also for old readers who might want to take another look.

1. THE MISSING JOURNALISTS & CLAUDE

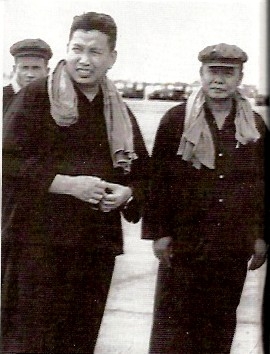

(Above Left) Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge leader, with his eastern zone

commander, So Phim.

(Right) Claude with So Phim at her release ceremony in 1970. |

|

In the 30 years I worked on the missing journalists, trying to establish what

happened to Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, I probably interviewed 5,000 or more

people including Vietnamese, Cambodians, Americans, French and a half dozen

other nationalities. I uncovered some very credible sources. But no one did

I trust more than Claude. I didn't have the slightest doubt that what she told

me was what she had experienced and believed.

Claude was captured in Cambodia the last week of April 1970 near the rubber

plantation area of Mimot, to the north of Phnom Penh, about three weeks after

Sean and Dana were taken. The headquarters of the North Vietnamese/Viet Cong

(COSVN) was nearby. Although she was taken by the Khmer Rouge, she realized

immediately that the North Vietnamese were in charge. She had been to Vietnam

the year before, had close Vietnamese friends, and she knew her interrogators

were not Cambodians, as they pretended to be. They spoke Vietnamese together

and took notes in the language.

Why were the Vietnamese running this charade with her? Why did they arrange

for such an elaborate release ceremony after only one week's captivity? Why

did they bring in a camera team to film her release?

At best, Claude was a minor freelance journalist and she didn't claim to be

anything else.

I realized that Hanoi wanted American journalists in Saigon to believe that

Sean and Dana and the others had been captured and held by the Khmer Rouge,

not the Vietnamese. They hoped that Claude would spread this disinformation

after her release. But she was freed around the time of the American invasion

of Cambodia, and her story got lost in the this far bigger story when the Americans

tried but failed to capture the COSVN headquarters where she had been held.

The validity of my hypothesis hinged on the identification of the Cambodian

who one night, drunk, came close to trying to rape Claude. He spoke French and

told her he was the eastern zone commander of the Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot's close

colleague, one of the ten top-ranking Khmer Rouge. He had recently arrived from

hiding out for years in Vietnam.

If this Cambodian was So Phim, the eastern zone commander, and he wasn't in

charge at this point, it strongly indicated the information we had collected

was correct. It was the North Vietnamese who had moved the journalists to Kratie.

I set out to try to confirm that the man photographed with Claude was indeed

So Phim. But it turned out that So Phim hated the camera. There were no known

photos of him. Even the war crimes documentation center in Phnom Penh didn't

have his photo. The head of the documentation center showed me So Phim's file

and said the photo I showed him closely resembled the written description of

Phim which they had gathered. Short, darker-skinned that most Cambodians, high

cheekbones, a distinctive curving mouth. The documentation chief said So Phim

was known to get drunk and was a brutal killer.

On two trips to Cambodia, in 2001 and 2002, I showed the photo of Claude and

So Phim to several dozen ex-Khmer Rouge, including his secretary and second

in command. Every one of them denied they'd ever seen the man in the photo.

I suspected that my partner and translator, Sos Kem, the only native born Cambodian

to serve as a U.S. Foreign Service officer, was beginning to think I was crazy.

The two biggest liars were Ieng Sary and his wife. Ieng Sary was the former

Khmer Rouge foreign minister, his wife was Pol Pot's sister-in-law.

Ieng Sary and his wife, I knew from info collected, had been initially in charge

of the journalists when they were captured and moved to Kratie. Sary picked

the Hanoi Khmer, who also spoke French and English, as the newsmen's camp commander.

They both denied that they knew the man in the photo with Claude, who was one

of their closest comrades.

Sary's wife was fascinated by the photo, though, and asked me after the interview

for a copy this original Letter.

The Sarys are being held for possible prosecution for war crimes, though I

don't think it will happen.

With Ieng Sary and his wife in Phnom Penh, 2001. (Photo by Sos Kem) |

When Sos Kem and I walked outside after the interview, we both said

simultaneously:

"They would have killed us in a second if we had been in their

hands."

Mrs. Sary's sister was Pol Pot's wife, also Sos Kem's teacher in high

school. I asked Sos what subject she taught.

"Ethics," he said.

I was frustrated by not being able to confirm that Claude's captors had included

So Phim. But I had to leave it that. There just didn't seem to be any other

photo of him in existence. Then one day I bought a copy of the newly released POL POT by British author Philip Short (Henry Holt & Company: 2005).

When I finally reached the photo section, I did a double take. There he was,

So Phim, looking ravaged by malaria and aged by the genocidal war he had fought

since Claude was released. This is the photo of Pol Pot and So Phim that appears

at the beginning of this section.

I knew how So Phim had died. Near the end of the war, before the Vietnamese

invaded Cambodia and toppled the Khmer Rouge, So Phim discovered that his brother-in-arms,

Pol Pot, planned to kill him. At first So Phim couldn't believe it. Nobody had

been more loyal to Pol Pot. But when Pol Pot sent troops to bring So Phim to

a "meeting," he knew it was the end. Sick and weak from malaria, he

announced he was going to commit suicide. But he had no weapon. He grabbed the

AK-47 of his bodyguard and wrested it away, accidentally killing the bodyguard

in the struggle. Then he killed himself.

When I showed the photo to Claude, she had a flashback and suffered something

akin to the post traumatic stress syndrome. It hit her viscerally for the first

time how close she had come to being raped and killed. She was shaken for days.

2. WALLACE TERRY & THE INTEL ATTACK ON ME

Wallace Terry and I grew closer after we went on the operation to recover the

bodies of John Cantwell and the three other journalists killed by the Viet Cong

in Saigon in 1968. Wally wrote an article about the incident for Parade magazine

some years later, entitled "A Friendship Forged in Danger." Although

I lived in Spain and then France, we stayed in close contact, and his home became

my second home when I was in the States. He wrote a bestseller about blacks

in Vietnam, called BLOODS, but he was never too busy to help me with

my own work.

So I was looking forward to seeing Wally when I arrived in Reston, Virginia,

to stay with him and his family in January 2003. For several reasons. I had

a problem and needed his advice. But even before we shook hands, I could see

that Wally was ill. He was losing weight and had a persistent cough. No one

wants to tell a friend he looks bad, and I tried to bring up the subject as

delicately as possible. But he waved me off.

"It has been a tough winter and I've got a cold I can't shake," he

said. "But it'll go away when spring gets here. What's up with you?"

The year before, in February 2002, I had returned to Cambodia to try to recover

the remains of Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, who I believed had been executed by

the Khmer Rouge in Kratie in late 1973 or early 1974, after being held for three

years. Wally helped organize my trip. Since I was operating on my own, he raised

some money to help cover my expenses, including a thousand-dollar contribution

from Murray Gart, the former chief of correspondents for Time magazine who had

asked me run the initial investigation in 1970. Wally knew practically everybody

in Washington. He used his contacts to encourage the Pentagon's war remains

recovery team to work with me.

I linked up with the Pentagon team in Kratie, a Mekong River town in the north.

But things didn't work out as I expected. Instead of offering their cooperation,

the sub-team from the Defense Intelligence Agency immediately began to treat

me like I was under investigation. I had been warned by friends with close contacts

at the Pentagon that the DIA agents would consider that I was meddling in their

business. But it was even worse than that. The DIA guys also had a bullying

attitude toward the Cambodian sources who could possibly help us recover Sean

and Dana's remains. They didn't want to resolve the problem. The DIA wanted

to discredit me, and they wanted to intimidate the Cambodians.

After I complained to the marine colonel in charge of the whole recovery team

about the DIA's bullying attitude, five DIA agents followed me to a restaurant

in Kratie one night. Our discussion started calmly but it wound up as an heated

exchange of words.

As I now know, this occurred not long after President George W. Bush signed

his secret executive order authorizing U.S. intelligence agencies to spy on

American citizens.

Shortly after my disagreement with the DIA, I suddenly found myself under surveillance

by the CIA and FBI in both the United States and France. Moreover, someone began

trying to wipe out my computer with viruses and break-in attacks. I got 700

hits on my firewall in less than two hours.

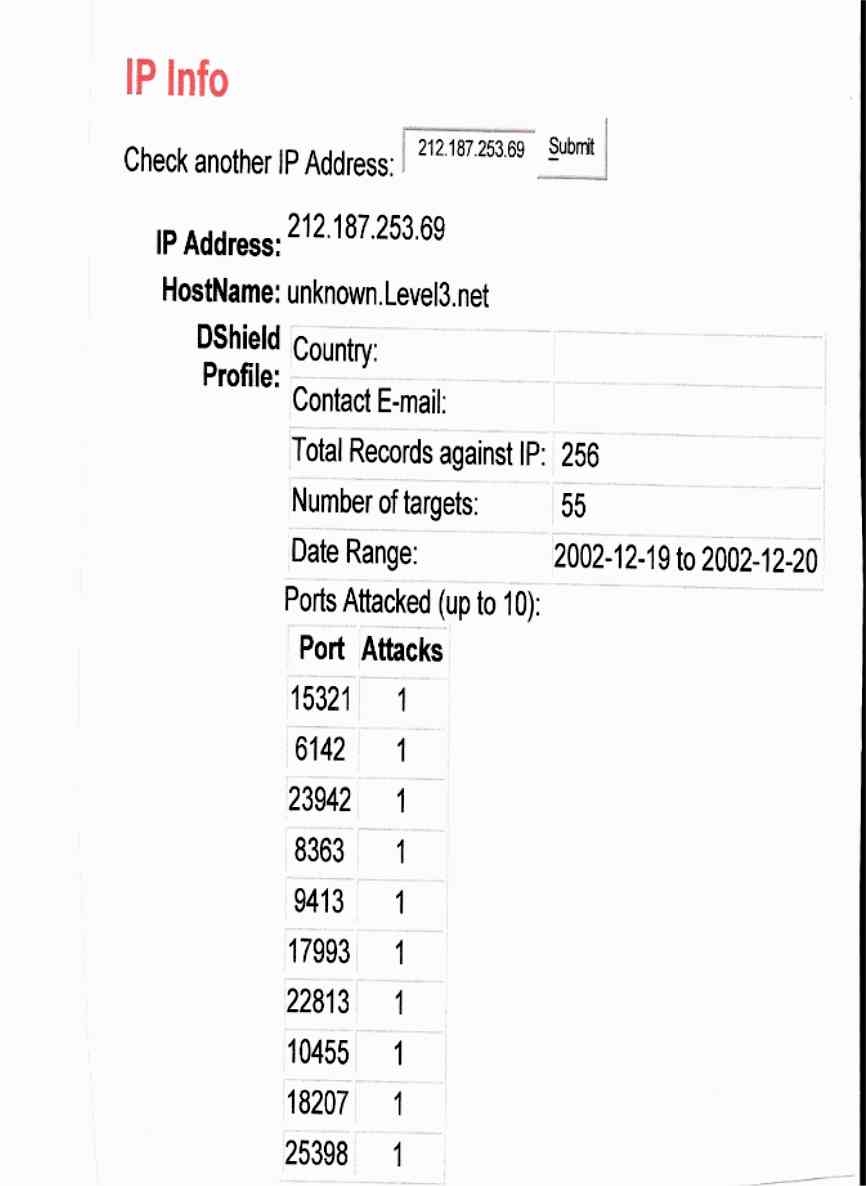

I had a software program that could backtrace where the break-in attempts were

coming from. Most of the attacks originated with an organization called Level3,

which I had never heard of. I soon learned that retired general Jay Garner,

whom Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld had picked as the first American proconsul

in Iraq, was a high official of Level3.

"Do you have any hard proof it is Level 3?" Wally asked, after I

gave him a run-down.

"Yes, I've got their IP numbers."

"What's that?"

"Internet Provider numbers. When somebody tries to attack your computer,

they have to go through an IP, and IPs have numbers that are registered with

the Internet. It is like tracing a phone number. They can't fake it."

Wally didn't know much about computers. Not that I did either, but I'd enlisted

a computer expert to help me figure it out.

"Here, I'll show you a copy of one of the IP numbers. When computer users

are attacked, they can file an abuse complaint against the owner of the IP,

in this case Level3."

"You mean they've got 256 abuse complaints against this one IP,"

Wally said.

"Yes," I said. "Their other IPs show similar abuse records.

Most people don't file abuse reports. Many of them don't even have the software

that can register IP numbers. This one computer could have been used to attack

thousands of Americans."

"It's the National Security Agency," Wally said. "I'm sure of

it. That's their footprint."

"Well, I don't know, Wally," I said.

"Could you figure out where it is coming from?"

"It looks like Menwith Hill in England, I don't know."

"You mean the NSA facility!" Wally was getting excited. "I told

you so. Do you have any other of their IP numbers."

"Yeah, I've got plenty."

'Hey, man, you've got hard proof. You can find a lawyer to take it on contingency

and sue these people for five billion dollars. That'll smoke them out."

"I'm not sure I want to do that," I said. "But I do want to

get them off my back."

"Let me think about it," Wally said. "The first thing we should

do is take this to the Vietnam Veterans of America. You volunteered for Vietnam

and had a good record as an army officer. I know the VVA likes your work on

the war. SURVIVORS and OVER THE BEACH are classics. I'm going

to phone Rick Weidman right now."

I later overheard Wally on the phone to his elder son Tai, saying, "They're

after Zip. It's like Three Days of the Condor." He was still coughing

but he didn't seem as sick, now that he was excited about helping me.

A report of an IP attack on my computer. Journalist and Author Wallace

Terry believed Level3 was actually the National Security Agency.

|

Wally had graduated from Brown and was editor of the college paper back in

the days before affirmative action was invented. He worked for The Washington

Post and then moved to Time, where he carved out a reputation as an expert on

African-Americans who had served in the Vietnam War. I was the military veteran,

not Wally, and I knew the leadership of the VVA, but Wally had developed a very

close relationship with them. He gave lectures to the VVA chapters in every

state. He constantly listened to the problems of vets and tried to help them.

Wally was highly beloved by the men and women who had served in the Vietnam

War.

"I talked to the VVA," Wally told me. "They are interested in

helping. They've had some suspicious incidents themselves. Two vets were complaining

to the Pentagon about the Agent Orange issue. Suddenly, both of them received

viruses that wiped out their computers. One of them bought a new computer and

when he went back online he was wiped out again. I tell you, the National Security

Agency is waging cyberwarfare against American citizens. We've never been able

to trust those people. They'll harass and spy on Americans in a hot minute if

Congress lets them get away with it."

"I don't know about that," I said. "But I do know American surveillance

teams are following me in Paris. And the surveillance includes young American

women. I think it's risky and irresponsible to expose them like that, considering

the hatred that Bush has stirred up against Americans all over the world."

The VVA assigned a lobbyist to help me take my case to Capitol Hill. Carl Tuvin

didn't fit the image of the "sharpie" lobbyist. He was laid back and

soft spoken. And he was obviously highly respected on the Hill. He arranged

our appointments with Congress in an amazingly short time. It took us all day

to make our rounds on February 11, 2003.

Jay Rockefeller's chief of staff on the Senate Intelligence Committee, a young

woman, told me they had already picked up reports that other Americans were

being spied on and harassed by the intelligence services. Chuck Hagel's staff

was sympathetic but didn't seem surprised either. The congressman from the district

in South Carolina where I grew up came closest to telling me the stark truth.

Bush had used 9/11 to castrate the Congress, and he could do little to help

me.

I knew before I started this would likely be the response I'd get. The country

was scared. The intel services were seen as saviors--at least by Americans who

had never met anyone who worked in intelligence. I had known intelligence officers

my entire mature life, and had held a top-secret security clearance myself..

Some of them were great guys whom I respected, others were jerks and scoundrels

hiding behind the shield of national security and secrecy to conceal their incompetence.

They were not people who had descended from another planet possessing a superior

knowledge. They were ordinary Americans whose lives were usually buffeted by

the same kind of chaotic problems as other ordinary Americans.

As I often told them, "We live in an era of technological geniuses and

analytical idiots."

They could collect every word we spoke or wrote. But then they didn't know

what to make of it. There were about a combined 100 thousand people engaged

in intelligence in the Washington area. Of that 100,000, no more than 300 were

fluent in Arabic--which happened to be a language of major concern. No wonder

they found it more interesting to spy on Americans.

Anyway, I was satisfied and appreciated the help Wallace Terry and the VVA

gave me. I had left a paper trail on Capitol Hill detailing what the intelligence

services were doing to me. Maybe in the future, if and when Congress resumed

its constitutional duties of oversight, my story could be used to encourage

the intel guys explain why they had been involved in such widespread illegal

activities. Until that point, I knew, they would continue with their program

of harassment and spite. It looked like they had taken me on as their life project.

But I wasn't worried about them, they could--oops! Don't let me get into what

I really think about them. I was worried about Wally. Before I left the States

to return to France, I pressed him to undergo a complete medical checkup. He

hemmed and hawed until he saw I wasn't going to let up, and then he went to

get a chest X ray. It showed nothing but a little scarring from an old case

of pneumonia. His doctors could not come up with a diagnosis.

Six weeks after I left Reston Wally was putting on his coat while Janice waited

to take him to the hospital. He suddenly collapsed and fell into a coma. It

wasn't a cold. He had contracted a rare disease called Wegener's granulomatosis,

its cause unknown, which hits only about one in a million people. It begins

with cold-like symptoms and can be treated with medicine if caught early. But

his case was diagnosed too late. Wally held on for two months. He did not come

out the coma.

Wallace Terry's last act as a journalist was to help me. And that will be my

memory of Wally until I check out too.

www.wallaceterry.com |

Wallace H. Terry II

April 21, 1938--May 29, 2003

Wally and I liked this photo. It was taken in 1990 at the time he

wrote the story about our Cantwell operation for Parade magazine.

Wally's family included his wife of 41 years, Janice, and their three

children--Tai, Lisa, and David--and two grandchildren--Noah and Sophia.

Photo by Tom Wolfe for Parade |

3. THE MICHELE OPERATION & PHOTOGRAPHER HENRI HUET

Men at war who put their life at risk every day form quick and close friendships.

Trust and shared danger are the ties that bind. In normal civilian life, this

kind of friendship could take ten years to establish between two men, if then.

It's hard to say who were the "best" photographers in Vietnam, that's

a subjective judgment. Three-fifths of being a war photographer was having the

guts and gumption to expose oneself to the possibility of immediate death in

order to get the picture. I hit the ground when firing started and rockets exploded.

Photographers couldn't. They had to be moving around with their cameras.

Another two-fifths to being a good war photographer was based on sheer talent.

It involved an eye for composition and the kind of imagination that could recognize

in a second the emotional weight of the shot he was about to take. Good photographers

didn't just click away. They saw the photo before they took it.

When I added the three-fifths and two-fifths together, I got the sum of Larry

Burrows of Life and Henri Huet of the Associated Press. In my opinion,

they were the best photographers of the war. And I had the honor of calling

both of them my friends

Henri Huet was with me on the Michèle operation. Henri and photographer

Christian Simon-Pietri and Alain Raymond of AFP joined me two days after I arrived

at Landing Zone English. The three were French, and Simon-Pietri was a friend

from my Da Nang days. Henri Huet and I had been on many operations together.

He always managed to take a few photographs of me that I could add to my personal

collection. On the Michèle operation he shot a wonderful photo essay

which showed what we did from start to finish. But I was robbed in Naples during

my overland Singapore-to-Paris trip and lost the photos.

I visited South Carolina when my niece got married several years ago and had

the chance to renew my friendship with Robert Fraley, the adviser to the Vietnamese

troops on the operation, who lived in the same town.

When Fraley and I got together, the first thing I said was, "I would like

to apologize for putting your life at risk to look for my girlfriend."

Fraley immediately cut off my attempt at sentimentality.

"You don't owe me an apology," he said. "I went out on operations

every day. That was my job. I enjoyed being on the Michèle operation

with you."

I mentioned that I had lost Henri's photos.

"But you sent me a set of the photos," he said. "I'll make a

copy and you can take the ones you gave me."

I had completely forgotten I'd sent Fraley the photos.

Eleven photos were in the set. Here are three of them, all taken by the best

combat photographer of the Vietnam War--Henri Huet.

This is a classic war photo. Capt. Fraley and the Vietnamese commander of

the troops are poring over a map and discussing the operation. You can see

they are acting as equals, as colleagues and friends. Unfortunately, this

sometimes didn't happen between the Vietnamese and their American advisers. |

|

January 21, 1967- When Claude saw this photo, she said, "They are

really running." I said, "See the smoke rising from the treeline.

That's enemy fire. All of us tended to run when somebody was shooting

at us."

Colonel George Casey, commander of the third brigade of the First Cav,

assigned eight helicopters to me to run the operation. He did it at considerable

risk to his career. If something had gone wrong and we had lost the choppers,

how would he have explained it? "Oh he was just looking for his French

girlfriend"? Many years later, Casey's son, Lieut.Generall George

Casey, Jr, served as commander of U.S. troops in the Second Iraq War.

Father and Son, two fine men, both cast into unwinable wars by their government.

That's Capt. Fraley bottom left, holding the carbine. I'm next to

him to his left. We are both lending a hand, but not much more. The Vietnamese

soldiers and locals from the area did the heavy lifting and pushing as

we moved Michele's car three miles through Viet Cong territory. I felt

it a point of honor to return the car to Saigon and the French dealer

who had loaned it to her. When I went to make sure he got it back okay, he said one sentence to

me: "It was very dirty." I turned and left without a word.

|

Henri Huet was killed four years later, in 1971. Henri and Larry Burrows

died in a helicopter crash in Laos, along with Kent Potter of UPI. See LOST OVER LAOS by Richard Pyle and Horst Faas (Da Capo Press: 2003)

In Paris Henri's niece was finishing a biography of the uncle she never

knew, and she asked permission to quote me, which of course I gave, and

then added:

"I would be pleased if you say in your work and speeches that I

loved the guy, really loved him. Henri was very rare-- in warmth, talent,

and courage--and we must never forget him." |

|