Are you gay?

If so, you may live longer than other people.

I was wondering why so many women and men in our small village lasted until

their late 80's and 90's. So I went out and talked to them and their friends

and relatives. I soon realized that a common thread ran through the anecdotal

evidence I was collecting.

Time and again this is what I heard:

"Elle est très gaie."

Yes, it was mostly women who were the gayest. And they were living the

longest.

Our English word stems from gai, although of course its original

meaning has largely fallen into disuse. For the French, however, "gai"

remains the most popularly used term to describe someone with a merry

or sunny disposition. No other word in their language captures an attitude

toward life so perfectly.

Gay was what everybody said about Jeanne Calmet, a Frenchwoman who died

several years ago at the age of 122, the oldest person who ever lived,

based on authenticated records.

And gay certainly describes Alice Dalod (left, at 21), the oldest

person in our village. Born in 1896, she has touched three centuries and

is now 104.

Alice is taking part in Project Chronos, a French study begun nine years ago

to try to establish why so many people are living longer. The country had only

250 centenarians in 1950. They project that in the year 2050 possibly as many

as 750,000 people will live to be a 100 years old or more.

The French are looking for the answer in Alice's genetic makeup, examining

her DNA. But maybe they should look for it in her laughter.

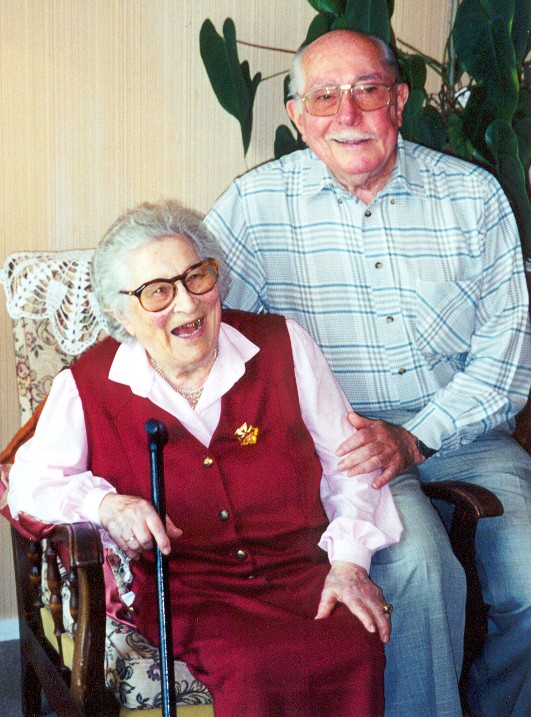

Alice Dalod, 104, our village's oldest person, with her

stripling of a son, Jean, who is only 79. |

Alice says: "I had a passion for work. I loved every minute

of it." She was a dressmaker and an artist of crocheting and knitting. She's

still at it, making gifts like these for her friends. At left, a hat used

to conceal a roll of toilet paper for an outing to the countryside. |

Obviously there is more to living longer than just being gay. Like everyone

else I talked to over 90, Alice loved her work with a deep passion; she was

a dressmaker. Like everyone else, too, she was moderate in her habits. She never

smoked, drank wine sparingly, and ate without excess--but also without the worry

that many people today invest in their diet. She still has for breakfast the

same thing she has had every morning of her life: black coffee and toasted bread

with real butter. She has never taken vitamins but has always eaten a green

salad with olive oil every day and plenty of fruit. She recently took up a new

addition to her diet--American iced tea, peach-flavored. (Iced tea has caught

on with the French public in the last several years.)

Alice lives alone. Her son Jean, 79, moved to our village several years ago

to make sure her needs were taken care of. He attends to her lunch each day,

but respects her independence.

"In life, stress is everything," Jean says. "She has no stress,

she's happy."

Angèle Perrin, who is going on 94, is almost a duplicate of Alice Dalod

in her lifelong habits. She never smoked, ate and drank moderately, and loved

her work. She ran the village hardware store for forty years, and gave it up

only when her husband died. She lives by herself, does her own housekeeping

and cooking. Not only did she always have a sunny nature, her woman friends

say she was très coquette (a big flirt)--a charge she accepts

with a smile.

Angèle Perrin at 20. Her friends described her

as "a big flirt" when she was young. At nearly 94 she is still a handsome

woman who lives alone and fully takes of herself. And she still has the

same glint in her eye. I took her photo, but decided not to use it. Let's

remember her like this. |

This is how the street where Angèle lived looked

when the photo at left was taken. It looks about the same today--and she

still lives there, Rue de l'Eglise. You can see the church looming in the

center background--a very fine example of 11th Century Romanesque. |

Angèle has never been in a hospital or clinic in her life. The others

I interviewed have enjoyed good health too, and studies have shown that a positive

attitude leads to less disease. My wife Claude's medical school classmate, Annie

Belaiche, is a top cancer specialist in Paris. Annie says that so many people

get cancer after being overwhelmed by some emotional problem that the anecdotal

evidence cannot be ignored.

Another reason people are living longer in France--an excellent medical system.

I find amazing the health benefits the French take for granted. Americans debate

whether senior citizens should have free prescription drugs. But the French

already have a long-running Social Security program that picks up from fifty

to a hundred percent of medicine costs for EVERYBODY.

In our village, people can walk into the pharmacy, produce the proper identification,

and walk out without paying a cent for their medicine. The pharmacy is paid

directly by the Social Security system. No fuss, no bother, it's all computerized.

Oh, and I forgot to mention: hospitalization and surgery are completely free.

Of course, the big question is whether the French can continue with such generous

benefits in future years. Where is the money coming from? Thirty years from

now there will be only two workers for every one person living off social benefits.

France is already one of the highest taxed countries in the world.

Back to real people

Jeanne Decorps, 94. Also lives by herself. Drinks a little wine every day.

She's a bit deaf but she has a truly incredible memory. She can reel off the

names of all 21 cafés that used to be open in the village. (There are

only two left.) She laughs and slaps the table as her memories come spilling

out. Her husband, who sold lemonade and beer, was a great cook, and they loved

to give long, boisterous dinners.

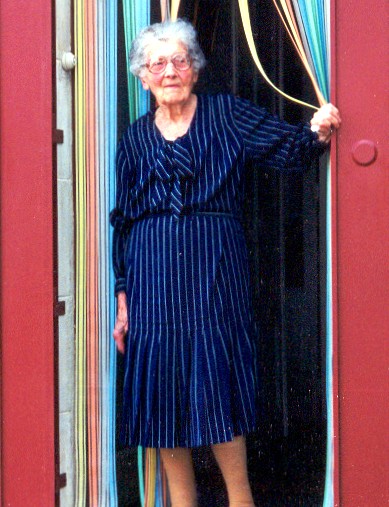

Jeanne Decorps, 94, in the doorway of her home. She liked

to eat, drink wine, and dance. She is still ready to play a practical joke. |

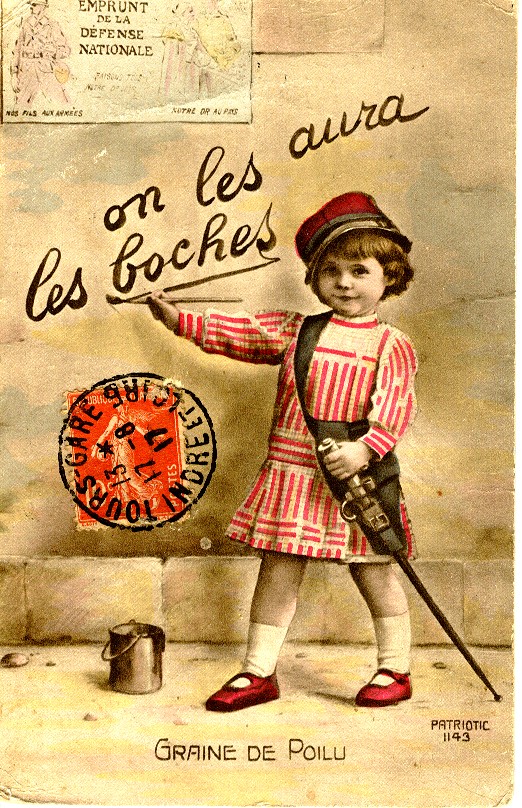

Jeanne sent her brother this postcard on September 17,

1917, during World War One. It says: "We'll get the boches" (Germans).

American forces had begun to arrive. |

Several of my personal friends

Hemingway wrote of "The Lost Generation" after World War One. He

was speaking about men. But in France there was a "Lost Generation"

of women. These were girls who came of age at the time of the war or shortly

thereafter and remained forever unmarried, because the war had taken such horrendous

toll of France's young men.

Two of these women, Madeleine and Lily Lamoine, were our closeby neighbors,

loving friends of Claude's father, Panou. They were classic examples of the

Lost Generation. Their father was killed in the war, leaving their mother as

one of 630,000 war widows in the country. By the end of the war nearly two million

Frenchmen were dead, putting the ratio between men and women of marriageable

age at 45 males to 55 females, where it was to remain for some years.

Madeleine and Lily were pretty and smart, but their future had been predetermined

by the war. They began work early, embroidering in their home, then taking their

wares by train to a nearby city to sell. There were boyfriends, but their mother

took precedence over their own desires to establish a family.

After their mother died, the two sisters continued to live and work together.

Madeleine, the older by three years, acted as the chief of the household. They

were known in the village as "les soeurs Lamoine," and "sisters"

in this case had a double meaning, because they were the mainstays of the church

and as dedicated as nuns--"les bonnes soeurs"--to helping people.

Claude often told her father Panou, who was very beloved by the village, that

only Madeleine would have more people at her funeral. When Madeleine died two

years ago, at 92, I took a rough count in the church and called it a tie. But

Madeleine may have edged out Panou by several chairs. I myself stood during

the service, in order to free up a seat.

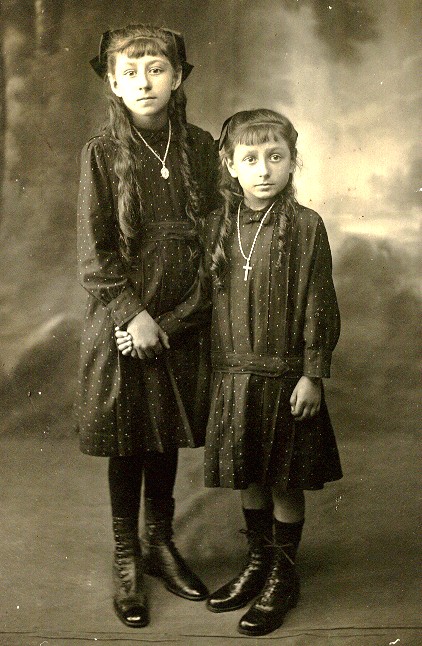

Madeleine and Lily at the time their father was killed

in World War One. They were classic examples of the "Lost Generation"

of French women--a widowed mother to take

of and few men of marriageable age due to the horrific casualties of World

War I.

|

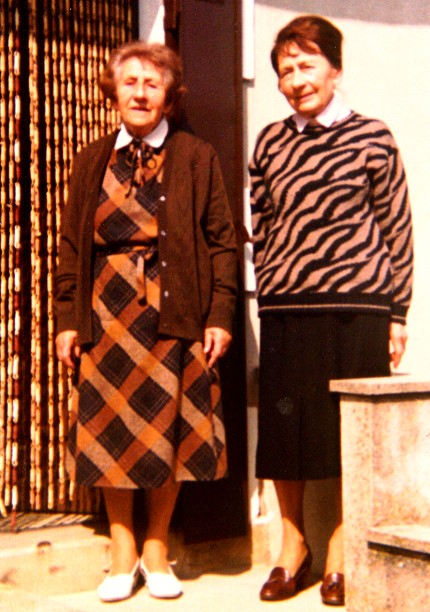

Madeleine (left) and Lily, in their eighties, when they

were our close neighbors. They had known and loved, Panou, Claude's father,

since they were kids. As at Panou's funeral, the church was overflowing

two years ago when Madeleine died.

|

We started to visit Lily, who is still in good health at 92, but discovered

that she had checked herself into a retirement home without telling anybody

in the village. Ever independent, she had no wish to be a burden on anyone,

she said.

Jeannette, 92

I asked Claude to phone Jeannette and set up a time for a photo session. "Tell

her to wear a dress, so she can show her legs," I said.

"Are you crazy," Claude said. "I'm not going to tell a 92-year-old

woman that."

She didn't have to. When Claude phoned, the first thing Jeannette said was,

"Does Zalin want me in a dress or a pants suit?"

Jeannette and I at her home. I say if you've got it, why not flaunt it--even if you are 92-years-old. |

Jeannette is a good amateur photographer, and I knew she would make the

setup herself. Sure enough, she suggested that she sit in a chair, with

me behind her. Claude snapped the shot.

Jeannette and I share a love of oysters, and every Christmas and New

Year's Eve I take her a dozen along with a bottle of white wine, and open

them while we have a drink.

I was asking her about wine when we were doing the photo, and she said

she now drinks a glass of red Bordeaux at lunch and in the evening. Her

doctor, she said, had prescribed it.

"Only two glasses?" I said.

"Oh Zalin, you know I never got tipsy," she said.

No, but wow! could she knock it back when she was in her eighties.

That's not the final answer, I know, to living the longest. But let's

pretend it is. A glass of wine twice a day keeps the doctor away.

|