| As a winemaker, Roland Hugonin's Eureka! moment occurred in 1983,

after he used his tractor to pull a car whose brakes had failed from the river

where it had wound up. The driver was uninjured but a little shaken, and Roland

invited him to his wine cellar for a glass. He turned out to be a Champagne

maker from Epernay, in the north, who was passing through.

When he walked into Roland's cave, he said, "This place smells

just right, it's the real thing."

Roland sheepishly confessed that he was not a very good winemaker.

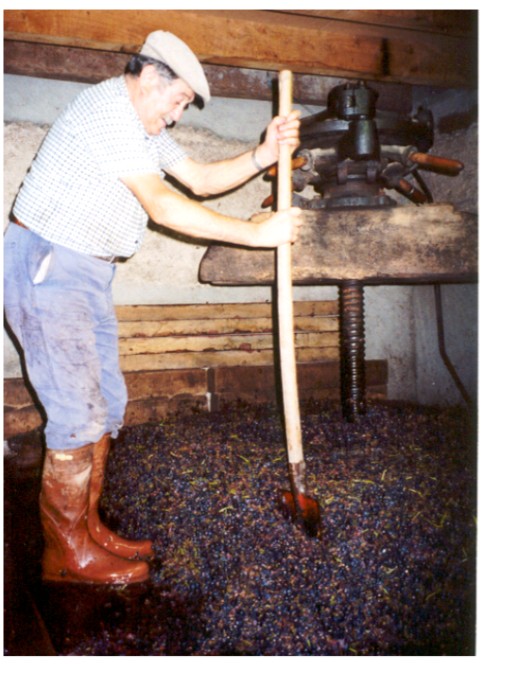

Roland Hugonin, 64, our village winemaker. His vineyard was passed down from his grandfather. |

"Well, I only know how to make Champagne," the man said.

"But I've got a friend who is a vigneron in Beaujolais and

I'll ask him to help you."

And he did.

"The quality of my wine improved by fifty percent," Roland

says.

All over France other winemakers were having their Eureka! moments,

too.

Like Roland Hugonin, many of them had not been formally schooled in

wine-making, they had simply a followed tradition going back a thousand

years.

The idea of following tradition sounds desirable and nostalgic, lost to our

modern times. And in fact you can't trump it when it comes to cooking. My

wife Claude quickly admits that French cuisine was better in her grandmother's

day. Women did not hold outside jobs. Time was not an issue, and they were

prepared to spend hours cooking. The smallest details were carefully observed,

there was no such thing as canned or frozen. And the quality of natural ingredients

(chemical fertilizer was unknown) was at its highest.

Oddly enough, tradition proved to be the bane of modern wine-making. It had

to do with a simple concept: cleanness and paying attention to details. It

wasn't entirely the winemakers' fault. The wine merchants encouraged them

to follow tradition. And tradition called for them to make the wine in the

same barrels each year--barrels that had been washed but not scrubbed beforehand.

It was thought that the old wine, still coating the barrels, gave a better

taste to the new wine.

The grapes of our village. French wine has never

tasted better in history--though consumption is dropping. |

In retrospect, the error seems obvious. Anybody can run a simple test.

Leave a glass of wine sitting for a day or two and you quickly discover

that it doesn't smell as good. Leave it sitting for even longer and

it takes on a vinegary taste.

So what would happen if you poured new wine into a barrel coated with

old wine that had been sitting there for months? Yes, it would produce

a wine of inferior taste.

But French winemakers, at least many of them, didn't realize this until

about twenty years ago, when scientific methods were applied to wine-making

and laboratory techniques revealed the error.

Today many winemakers have shifted to easily-cleaned stainless steel

vats for the fermentation process, after which the wine is put into

well-scrubbed barrels for aging.

Shocked by this revelation, winemakers suddenly realized that they had to

reassess the other steps in wine-making which they had taken nonchalantly

as routine and not worth consideration--the old "we've-always-done-it-that-way"

syndrome. They realized that absolute cleanliness had to apply from the moment

the grapes were harvested until the wine was corked in the bottle. They also

had to pay attention to the smallest details of each step in the process.

So the wine of our village's Roland Hugonin has become quite drinkable. Our

area has never produced anything of higher quality than table wine. Why? That's

one of the mysteries of soil and sun. We sit on slopes overlooking a valley

formed by the Cher River. Good drainage and decent soil. But nobody will ever

suggest that we have wine on the level of a Burgundy with an AOC grading,

not to mention something like a Savigny-Lès-Beaune, one of Claude's

favorite wines, which our guide book describes as having a very good bouquet,

subtle, perfumed, and mellow. (We both prefer Burgundy to Bordeaux, no doubt

a heresy to many wine experts.)

Barrels outside our village winemaker's. After making wine for 1500

years, French winemakers discovered 20 years ago that scrubbing the barrels

before re-using them would give their wine a better taste. |

Yet, despite the unremarkable quality of the wine, our village was

born from the vineyard, as the French say. One big reason was that there

were plenty of churches in our area, and the churches needed a lot wine.

In 1095, the Lord of our village, Humbaud le Jeune, gave a vineyard

to the parish, "under the condition that the wine serve exclusively

for the Saint-Sacrifice [mass]."

It sounds like the Lord was a little suspicious of the priests. And

indeed, a couple of hundred years later one of them was still complaining

that the wine wasn't strong enough.

Just before the phylloxera hit in 1886, there were 1200 hectares (485

acres) of vines in our small area alone.

Phylloxera was the Black Death of wine-making. Nobody knows where it came

from, but it started in the south of France. Grape vines shriveled and died.

No treatment worked. It hit our village on May 24, 1886, when someone brought

a vine for grafting from the south. It was a disaster all over France. When

it hit here, our village was thriving, with 3,000 inhabitants. Today, we have

about the same number. Time just stopped.

A solution was found by importing American vines, which were resistant to

the disease. The phylloxera infested vines were destroyed and the American

vines planted. But this was an expensive proposition and though the village

was relatively wealthy, it was wealthy in land, not money. One by one, families

went under. There was a brief Renaissance after World War One, and it looked

as though the wine growers would recover.

But then the factories started pulling people from their farms. Slowly, over

the years, the vineyards disappeared (including the one on our farm), until

only Roland Hugonin was left, plus several others in the surrounding area.

Monsieur Hugonin has proved to be a wonderful keeper of the flame. He is passionate,

articulate, full of facts about his subject--also anecdotes. Ask him a question

and he says, "First, let me tell you an anecdote about this." And

off he goes on a witty flight that hedgehops over the vineyards and cellars

of France.

When friends and clients visit Roland Hugonin's wine cellar, they

get not only wine but also a witty and passionate dissertation on this

marvel of life. Hanging from the ceiling are his awards from

local tasting contests. "I used to wind up last or maybe eight or ninth," he says.

"Now I sometimes take first prize."

|

La Vendange

There is specific work to be done in wine growing which changes with the

months. November-December is the time the soil must be worked to protect the

vine from the cold of winter.

March is one of the most important, upon which much hangs. There is a saying

among wine growers: Taille tôt, taille tard, rien ne vaut la taille

de mars. (Prune early, prune late, nothing is better than to prune in

March.) How well you prune will determine the size and quality of your harvest.

And pruning is not easy. It's an art form which takes the equivalent of a

super green thumb. The last time I pruned one of our vines, it up and died

on me. Claude was not overly amused.

But nothing is more anticipated than the vendange, which takes place

from September 20 to early October, depending upon the region and the weather.

The translation of vendange is "grape-gathering." But that

sounds far too prosaic. It carries none of the emotion that falls like poetry

from French lips when they say "vendange." The French are

not a very smiling people, but they never say vendange with a frown.

It is a happy word.

How the vendange is carried out varies from region to region. Each

has its own traditional costumes. Even the baskets used to carry the grapes

are different. In Burgundy they use woven baskets; in Bordeaux, the baskets

are made from wood. One thing is the same: they all celebrate with plenty

of wine and food and dancing.

The vendange is sort of like the old barn-raising times in America,

when neighbors came from miles around to help build someone's barn. At Roland

Hugonin's last vendange 58 people showed up, some of them musicians

who travel around our region playing at fairs and feasts, to maintain a tradition

that goes back centuries.

|

What do you do before starting out on the vendange? Of course. You start off with "un p'tit coup." Roland's rosé is as good or better than a regional rosé

from Provence.

|

Arriving at the vineyard. Note their wooden shoes, called "sabots."

I remember as a kid being intrigued to learn that is where the word "sabotage"

came from. They threw their wooden shoes into the machinery to disable

it. |

New Wine in Old Bottles

Ironically, at the time wine began to get better, the French started drinking

less. The improvement in taste happened to coincide with cultural changes

that swept the country. Mainly, it had to do with the young. They began to

opt for Coca-Cola, which went well with another trend, heretofore unknown--eating les snacks. (The young French are paying the same price as their American

counterparts: They are getting fatter.) The average person's consumption of

wine dropped from 26.5 gallons a year in 1960 to 14.5 gallons now and is still

declining

Consumption has dropped among mature adults. There are growing health concerns

about the use of alcohol, which constitutes a major change in attitude, because

the French used to be in denial when it came to wine. They avoided thinking

of it as potentially dangerous alcohol and considered it as just a benign

accompaniment to their meals, even though, of course, they knew better, since

evidence of alcoholism was all around them. They have also discovered that

operating a computer becomes a bit of a problem after a long lunch bien

arrosé (well watered). The number of daily drinkers declined from

47 percent in 1980 to 24 percent today.

Nothing like a little traditional music to stir you up for the backbreaking

labor of harvesting grapes. |

How do me and my friends--older guys--feel about this decline in consumption?

Oh, it's really terri--well, wonderful! Since there is not much of a market

any longer for cheap wines, the French have given up the idea of quantity

and replaced it with quality. Vineyards in the south that used to produce

a lot of drinkable but unremarkable cheap wines have been abandoned or pulled

up and turned into prime real estate. The wine has got to be good or it won't

sell. Since it is all a matter of supply and demand, you can now find good

wines at cheaper prices. These are usually regional wines that don't travel

very well--certainly, they would have a nervous breakdown before making it

to the United States and never taste the same

After the ceremony, it comes down to this. The grapes are carefully

cut with pruning scissors and

then transferred from individual baskets to a larger one, which is emptied

into a barrel. |

Qualité/Prix

The French have never been ones to throw around their money. And searching

for a balance between quality and price has always been a part of buying wine.

What wine you buy depends upon the occasion, depends upon the people involved,

depends upon your budget. I am writing this on a Saturday morning. A friend

has invited us to dinner this evening, to meet several doctors who are friends

of theirs. This will be an above-average occasion, but nothing truly special.

I will report on what wines were served when I pick this up tomorrow morning.

Sunday - It was an agreeable evening, as it always is at Robert and

Odile's (see "The Model Surgeon"). The guests included a biologist,

a pharmacist, a doctor and his wife, a beautiful woman from Mauritania. You

can be sure that nothing out of the ordinary will happen at a dinner party

like this. Even at their most informal, the French are still more formal than

Americans. This sometimes leads to a certain blandness in the conversation,

since everybody steers clear of controversial subjects. On the other hand,

you don't go home and spend the night awake, telling yourself, "I should

have said this, when he (or she) said that." Robert made a piece of veal,

cooked four hours in a quart of vinegar with tarragon, as the main dish. When

he later asked me what I thought, I said, "Very good, though not quite

as good as Claude would have done it." He said, "You have put me

in an impossible competition, and I accept the compliment. Thank you."

Anyway, the wine. As an apéritif to go with foie gras on toasted bread,

Robert served a white Bordeaux sauvignon, a 1998 Château Les Sept Chênes,

Appellation Bordeaux Contrôllée. The wine was recommended by

the chef Paul Bocuse to Robert's wine club. Price $7. To go with the meal,

he served two different red Côte Roannaise, which is close to a Côtes

du Rhône, and comes from Renaison, about 70 miles from Lyon. The wine

is made by Robert Serol, and he is our preferred vigneron; we know him and

his wife and family. In fact, it was Claude who took Robert to Serol's to

buy this wine while I was in Cambodia. The Michelin 3-star restaurant, Troisgros,

is located in nearby Roanne, and Robert Serol has a deal with Pierre Troisgros

to produce a joint-labeled wine. It has an AOC. Again, we are talking quality

versus price. The Pierre Troisgros/Robert Serol bottle cost five dollars,

the other one three dollars. So Robert spent a total of $15 on his wine. For

simply an above-average dinner party, the wine was appropriate and enjoyed

by all. Similar wines were being served at similar dinners all over France

on Saturday night.

After the harvest, Roland Hugonin prepares his grapes for pressing. |

This emphasis on quality/price is not so much based on money as it

is on the chase. It's sort of like an Easter egg hunt. We have spotters

who phone us when a good regional wine shows up in one of the discount

chains.

When a good regional appears, the word goes out and you'll see Mercedes

and BMWs parked at the place where it is on sale. It is soon gone, maybe

not to reappear for several years.

Men have traditionally been responsible for the wine, but women are

now playing a more active role, of course humoring the men as they do.

I send Claude out on scouting expeditions. She has the kind of personality

that makes men want to help her choose a good wine.

Just the other day, for example, she was looking over the wines at

a shop and a guy walked up and recommended a Coteaux du Tricastin, which

carries an Appellation Contrôlée and comes from near Provence.

She bought a bottle and brought it home for a tasting. This was our Eureka! moment. It was quite good. She hopped back in the car

and went to buy two cases. It cost $2.30 a bottle.

Of course, this competition sometimes gets out of hand. My friend Max likes

to one-up everybody. We were sitting outside under the lime tree the other

day, and he was telling me about his success in renovating a friend's house,

installing the electricity, a bathroom, everything. I believed him.

In between chain-smoking one of his cheap Gitanes, he suddenly said, "I

found a Bordeaux, a regional without an AOC or anything, but really good."

He kissed his finger tips for emphasis. "Guess how much it cost?"

I wasn't going to play his game. I knew what was coming--something outrageous.

"I don't have a clue, Max," I said.

"A buck forty a bottle," he said. "Dix balles."

I stared at him.

"Well," he said, looking away, as he lit up. "I admit that

it was on sale as a loss leader to draw customers in."

Most French special occasions have a certain symetry--they start with

food and wine, and end the same way. We certainly could expect no less

of la vendange. "À la votre, Monsieur Hugonin!" |

Searching for Monsieur Moderation

Roland Hugonin is fond of saying: "I always try to drink with moderation.

But I can never find Monsieur Moderation, so I have to drink alone."

He is just kidding, of course. Although I had met Monsieur Hugonin only casually,

he and I shared a close friend, Louis Marceau--"P'tit Louis." A

handsome guy with a beautiful soul, beloved by Claude's father, Panou, and

everybody else in our neighborhood. He never got married, and there were whispers

of a sad tale of unrequited love. Whatever the cause, Louis Marceau had a

problem.

I was passing his house on a walk with my dog early one morning, and Louis

Marceau stopped me. "Zéline [giving my name the French pronunciation],

come in and have a drink." I entered his small, bachelor-in-disarray

house, and he proceeded to pour me a drink--a water glass full of eau de

vie, a clear brandy distilled from the residue of the wine grapes. He

was charming, irresistible, you had to love him. Since Louis Marceau had his

own vines, he made his own wine and eau de vie. From then on, I took

another route on my morning walk. He died at age 52.

So it is not a bad idea that the French have cut back on their consumption

of wine. Forty percent of their auto accidents are associated with alcohol.

I try not to get on the road after lunch for any distance. Still, even with

the cutback, the French remain the world's largest consumers of wine, drinking

920 million gallons a year, 16 percent of the world's total. I have a feeling

wine will be around for a long time.

As for Roland Hugonin, he is retiring. In order to qualify for his pension,

he must destroy a part of his vineyard, leaving enough vines to provide wine

only for the private consumption of himself and his friends. He thinks someone

else will take over to maintain the tradition.

Sadly, I don't believe it. But we are left with the hopeful thought that

somebody will, and the words of the poet Thomas Moore:

What though youth gave love and roses,

Age still leaves us friends and wine.

The Village Winemaker and I on May 15, 2001, at 10:30

a.m. Sipping wine on an empty stomach during a morning interview is pleasant,

but it definitely has a downside: I couldn't read my notes. Luckily, he

is such a vivid personality that I had no trouble remembering. |

|