Sos Kem and I were not in a terrific mood.

We were standing outside our Phnom Penh hotel, waiting in the muggy, predawn

darkness for the ride that would take us to the place upcountry where I believed

Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, and maybe a dozen more journalists, had been held

by the Khmer Rouge after they were captured in 1970.

Zalin Grant with ex-Khmer Rouge foreign minister, Ieng

Sary, and his wife. I believe they were responsible for the newsmen after

their capture in 1970, but he denies it. (Photo by Sos Kem--Feb 5, 2001) |

Sos and I were irritated because we thought the Pentagon had tried to

sabotage our trip.

"Maybe it's not what we think," I said to Sos. "Sure,

we've invaded their turf and they undoubtedly don't like it. But you can

never overestimate the Pentagon's propensity for screwing up because of

disorganization."

"Maybe," Sos Kem said.

I knew he didn't believe it.

Two days earlier, on Wednesday, we had met with the air force colonel

who commanded the Cambodia detachment of the Pentagon's missing-in-action

team.

We asked him if we could use his helicopter on Friday morning for a

trip upcountry where we believed the journalists had been held.

The site was 45 minutes away by helicopter but four and a half hours otherwise,

first by vehicle and then by water taxi up the Mekong River. And we were pressed

to get back to Phnom Penh as soon as possible, because we had an interview set

up on Monday with the former Khmer Rouge foreign minister, Ieng Sary.

"I think the helicopter is a good possibility," the officer said, " but let me phone tomorrow to confirm."

Until that point, it had been pretty much of a one-way street between the Pentagon team in Phnom Penh and us. The lieutenant colonel had provided me with a letter of introduction, as requested by the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff of Cambodia's armed forces. But I had turned over several important reports to the Defense Intelligence Agency guys who were operating as part of the team.

One of the reports pinpointed the possible location of the missing newsmen. This was information that the Pentagon team, with its staff of 455 and an annual budget of millions of dollars, had been unable to develop after nearly ten years in Cambodia.

When we didn't’t hear from the lieutenant colonel by noon the next day, we

assumed that we would be taking the helicopter. Why else would he wait so late

to tell us? After five p.m., the officer had his sergeant to phone Sos Kem and

inform him that the helicopter wouldn't be available, after all. No further

explanation. He didn't return my phone call.

That meant we had less than one hour, in Cambodian working terms, to set up

alternative transportation.

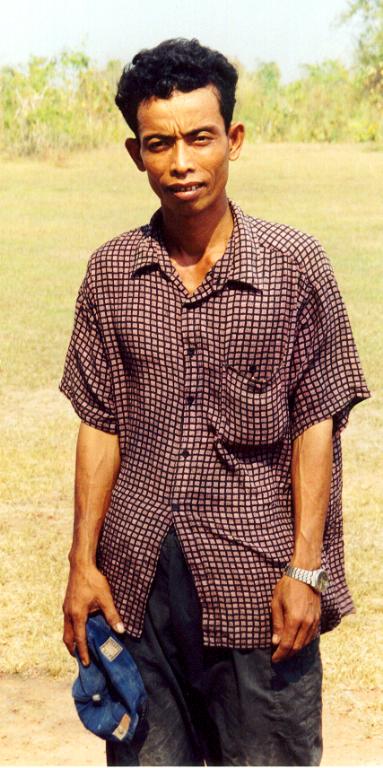

Sos Kem, a naturalized American, is the only Cambodian

to serve as a U.S. Foreign Service Officer. Sos is also a walking "No Smoking"

sign. |

|

"Maybe it was simply an act of discourtesy," I said. "He

obviously could have told us earlier."

"Sabotage," said Sos Kem.

I laughed.

What the hell. Nobody was going to sabotage us. We would do it one way

or another.

Before we linked up in Phnom Penh two weeks earlier, I had known Sos

Kem only through e-mail. He was a naturalized citizen and the only Cambodian

to serve as a U.S. Foreign Service Officer. Now retired, he had worked

at the American embassy in Bangkok and Phnom Penh.

Sos was tall for a Cambodian, about five-eleven, and in his late-sixties but

looked much younger, his hair just beginning to go gray. He was smart and charming--though

he had, I discovered, a few eccentricities.

Smoking, for instance. He sniffed the air suspiciously wherever we went. He

hated smoking with a passion I'd never encountered. One day, when he discovered

that the Belgium army de-mining team which stayed at our hotel was not only

smoking but doing marijuana, he looked as though he wanted to toss them

off the restaurant terrace. He allowed his wife to keep an altar with a Buddha

back in their Washington suburban home, but she could only burn incense when

he wasn't there, and then all the windows had to be opened and the house aired

out.

Luckily, I didn't smoke or burn incense. We got along fine.

The National Police colonel who was our liaison with the Cambodia MIA office

came roaring up in a white Japanese-made SUV. We piled in and headed north out

of Phnom Penh for Kompong Cham, a major city about 70 miles away. The colonel

had phoned ahead to reserve a water taxi to take us up the Mekong. But we had

to be there by 8 a.m.

If there was one change immediately noticeable since my last trip to Cambodia

nearly 30 years before, it was the ubiquity of mobile phones. Everybody seemed

to have one, including the water taxi driver, fortunately for us. (After I used

Sos Kem's phone, he would carefully wipe it off on his pants.) We honked our

way through the morning traffic and hit Route Seven, a decent blacktop in a

country where most of the roads were rutted and cratered.

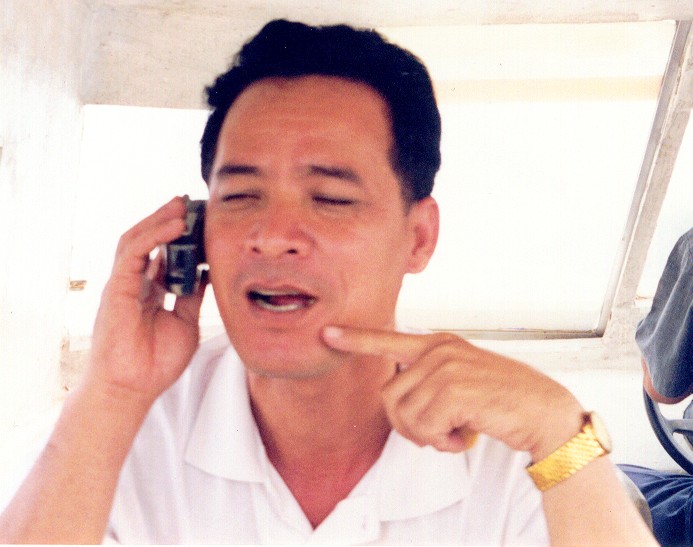

Colonel Chum Soyath, assigned by the Cambodian government

to serve as our liaison, also acts as the official liaison to the Pentagon's

missing-in-action team. Here we are in the middle of the Mekong, heading

upcountry, and he is talking on the phone to ex-Khmer Rouge foreign minister,

Ieng Sary. |

|

Houses on the banks of the Mekong River,without

running water or electricity, sprout antennas

of battery-powered TVs. Soap operas are popular.

|

Route Seven turned into the usual nightmare after Kompong Cham, though, which was why we had to shift to a water taxi. We barely made our eight a.m. deadline. The taxi driver was waiting for us impatiently as we pulled up at the ferry crossing. The colonel parked his SUV in the hotel lot across the street, and we scrambled down the bank to the boat--a fiberglass outboard, powered by a Yamaha 85.

There wasn't much traffic on the Mekong, the day was overcast and not too hot. The driver hit 30 miles an hour and didn't let up. We were passing flimsy huts that looked ready to slide off the high banks into the wide river. I was surprised that many of the crude houses sprouted TV antennas. This was post-genocidal rural Cambodia: no electricity or running water, no bathrooms--a 19th century standard of living, topped off by mobile phones and battery-powered TV.

The colonel's mobile phone rang. He asked the driver to stop the boat, to kill the engine noise so he could hear. It was Ieng Sary, the former Khmer Rouge foreign minister. Sary wanted to confirm our appointment for Monday. He also probably wanted to check on what we were doing. I knew he would be interested to hear of our destination.

Ieng Sary had picked the commander of the camp where the journalists were held.

How many people get to make a trip up the Mekong?" I said to Sos Kem. "This is better than a helicopter."

My irritation with the Pentagon team had faded. I had nothing against those

guys, and in fact didn't know anything about them until a month earlier, when

I began preparing for the trip to Phnom Penh and people started passing me information

over the Internet. I did not consider myself an MIA activist. But the missing

journalists were a piece of unfinished business in my life. I was one of the

few civilians who knew exactly how hard was the task facing the Pentagon team.

I had been there.

|

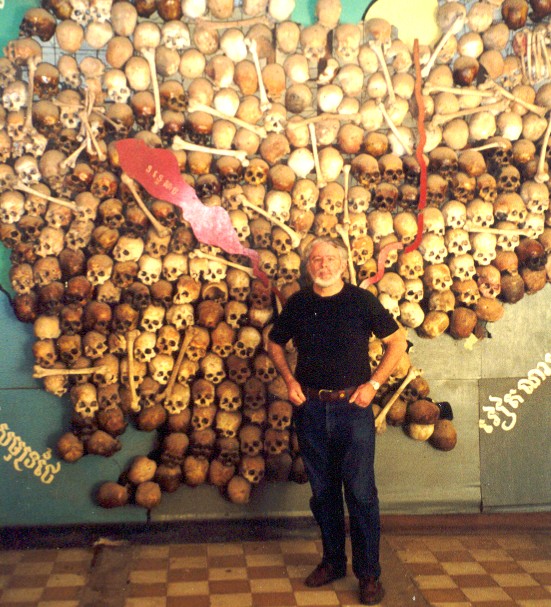

This is the obligatory photo for tourists visiting Phnom Penh.

It is the macabre equivalent of going to Paris and having yourself snapped

in front of the Eiffel Tower.

The purpose here is not a celebration of man's soaring spirit but as

a reminder of his sometimes dark and horrific nature.

Between 1975 and 1979, 1.7 million Cambodians died in what French writer

Jean Lacouture has called an act of "autogenocide."

This museum of genocide is found at the S-21 torture center--a former

French lycée--where 14,000 men, women, and children were tortured

and murdered.

|

NOTE

The piece above stops abruptly because it is part of a larger work, a book

to be called The War and I. The following article was written as a memo

to members of the old Cronkite committee. It describes what Sos Kem and I learned

during our trip to Cambodia in January and February 2001. Over the years, I

have received many queries about the missing journalists, particularly about

Sean Flynn. Sean Flynn was a handsome dashing war photographer and former movie

actor who was the son of a handsome dashing movie actor named Errol Flynn. Perhaps

the combination of all this and the fact that he was lost young has turned Sean

into a sort of cult figure for some people. To me, he was simply a friend and

fellow war journalist. Among the queries I've received, some have come from

people who wanted to make money by filming or writing about Flynn and Dana Stone.

Which is their undisputed right. As a writer, though, I feel compelled to issue

a reminder that the material collected during my private trip to Cambodia, as

reflected in the Cronkite memo, has been officially copyrighted with the U.S.

Registrar of Copyrights at the Library of Congress, in Washington, D.C. So has

a tape-recorded 3-hour interview I did with Sean Flynn a year before he was

captured, in which he talks about how he saw himself, as opposed to how others

saw him in retrospect. My work cannot be used or reproduced by any means without

written permission. In case there are a few people out there who don't understand

what this means, I'd be glad to introduce them to my longtime friend Melissa

Palmer, an American who works in Paris, a marvelous cook--and a great international

lawyer. Sorry for this rather blunt interruption. But if you knew what I know,

you would understand.

The Cronkite committee, established in late 1970, was made up of Walter Cronkite

of CBS, chairman; Peter Arnett of AP, secretary; Tom Wicker of the New York

Times, treasurer. The executive committee consisted of Barry Bingham Sr (deceased),

Otis Chandler, Richard Dudman (deceased), Osborn Elliott, Murray J. Gart, Katherine

Graham, David Halberstam, Ward Just, Frank McCulloch.

Here is the memo in its entirety.

THE CRONKITE MEMO

February 26, 2001

To: Walter Cronkite

From: Zalin Grant

Subj: Journalists Missing in Cambodia

From January 18 to February 13, 2001, my colleague Sos Kem and I conducted

an investigation in Cambodia concerning the approximately 17 international journalists

who disappeared in 1970, including three American citizens--Sean Flynn for Time

magazine, Dana Stone for CBS-TV News, and Terry Reynolds for UPI.

Sos Kem is a naturalized American citizen and the only Cambodian to serve as a U.S. Foreign Service officer. I spent five years in Vietnam as an army intelligence officer and then journalist, and later ran an investigation in 1970 and 1973 in Cambodia on the missing newsmen.

I have already provided much of the information in this report to the U.S. Defense Department's Joint Task Force--Full Accounting (JTF-FA), in a carefully hedged fashion, and my intention here is to lay out the same information in a more expanded and informal manner for the remaining committee members.

Summary

We established with reasonable certainty that the journalists were held at a Khmer Rouge camp near Kratie City from mid-1970 until early 1975, when they were executed and the camp was closed down and destroyed by the Khmer Rouge. We also established the possible gravesite of the journalists, which is several hundred meters from where they were held.

The camp was located at Grid Coordinates XU 154815, four kilometers east of Kratie City on Route 13, in the northwest corner of an abandoned airstrip. The area is easily identifiable on a 1:50,000 U.S. Army map, Sheet 6233 IV, Series L7016, 48P-XU. The gravesite is north of Route 13 and easily accessible from the road. The site has not been tilled or disturbed in the intervening years. There are no mines or other dangers in the area.

How and Where Were the Journalists Captured?

Most of the newsmen were captured within a two-day period in April 1970 at the same place--a longtime VC checkpoint on Route One in Svay Rieng province, a few miles from the Vietnam border. They were captured by elements of the Tay Ninh Provincial Security Battalion (Vietnam) and 9th VC/NVA Division. In addition, there were a few Khmer Rouge soldiers in the area.

A CIA-trained Vietnamese intelligence officer and I interviewed eyewitnesses to the journalists' capture in April and May 1970, several weeks after they were taken. The Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) team went over the same ground after the JTF-FA was established in 1992 and interviewed many of the same sources. Two years ago, the DIA team came up with an additional source--a Khmer Rouge squad member who was an eyewitness to their capture and initial disposition. The details of his account, as recorded in a DIA report that I have, coincided almost precisely on every point with the information the Vietnamese intelligence officer and I had collected in 1970.

What Happened to the Journalists?

They were almost immediately moved to the Kratie area, about 120 miles northeast

of Phnom Penh. An NVA lieutenant who defected saw two of six journalists being

held in a house near Kratie at the end of May 1970. The North Vietnamese was

interviewed and given a lie detector test by the U.S.525th Military

Intelligence Group in Saigon, which he passed. The JTF-FA did not have this

official 525th MI report. I gave it to them in Phnom Penh.

My 1973 Report to the Cronkite Committee

An eyewitness saw approximately ten of the journalists at the Khmer Rouge Camp (XU 154815) in mid-1972. He was a Cambodian who had long worked on rubber plantations in the Mimot-Chup area. The Khmer Rouge took him in 1972 to the XU camp for refresher training in rubber production and he later managed a rubber plantation for them, overseeing 455 workers. He defected because he wanted to join his family. I interviewed him extensively in Phnom Penh in April 1973. I considered him to be highly credible.

Thus I returned to Cambodia in January 2001 with the ultimate idea of checking out this report of the XU camp in Kratie. I told my colleague, Sos Kem, about the 1973 report in general terms but asked him not to read it until we were through with our work. I didn't want him inadvertently to nudge anybody into telling us what we wanted to hear by using specific details about the camp, and I wanted to make sure that he drew his own conclusions rather than be influenced by what I believed. Although Walter Cronkite put this file into the public record when he testified before a congressional committee in 1976, the JTF-FA did not have the report, nor did they know about the XU camp in Kratie.

My point of confusion was this: If the Vietnamese had captured and moved the journalists to Kratie, how did they wind up in Khmer Rouge hands? Pen Sovann answered the question.

Interview with Pen Sovann January 27, 2001

Pen Sovann was a Khmer Rouge propaganda officer who later defected to the Vietnamese

and was installed by them as the first prime minister after they drove the Pol

Pot forces out of Phnom Penh in January 1979. He also served as commanding general

of the Cambodian army. He later clashed with the Vietnamese and they threw him

in jail for eleven years. He is well known to U.S. government officials, and

has cooperated with the JTF-FA on finding the remains of U.S. military MIAs.

Pen Sovann said he learned from Ieng Sary and his wife Ieng (née Khieu) Thearith in July 1970 that the journalists were being held at the XU camp in Kratie. At the time, Sovann and the Sarys were at Khmer Rouge headquarters farther north, in Ratanakiri province. Ieng Sary later became the Khmer Rouge foreign minister, but at the time, according to Sovann, he and his wife (whose sister was married to Pol Pot) were in charge of intellectual affairs and thus the journalists fell under their responsibility.

Pen Sovann said the XU camp was an important liaison station with the Vietnamese where weapons were transferred to the Khmer Rouge. It was also used as a training center. As I understood him, he indicated that the Vietnamese effectively controlled the camp until after the 1970 Lon Nol coup, when they increasingly transferred control to the Khmer Rouge. Thus the Vietnamese did not transfer the journalists to Khmer control--they actually transferred the XU camp and everything that went with it to them.

This occurred in mid-1970 when the Khmers who went to Hanoi for training after

the end of the 1954 French war returned to Cambodia to join the Khmer Rouge.

Sovann said Ieng Sary was in charge of greeting and giving the Hanoi Khmers

their assignments, and that he assigned Prey Muth as the commander of the XU

camp. Prey Muth, whom Sovann knew personally, was originally from Takeo and

had been a schoolteacher in Phnom Penh at the time he joined the Khmer Rouge.

In addition to Khmer and Vietnamese, he spoke English and French.

|

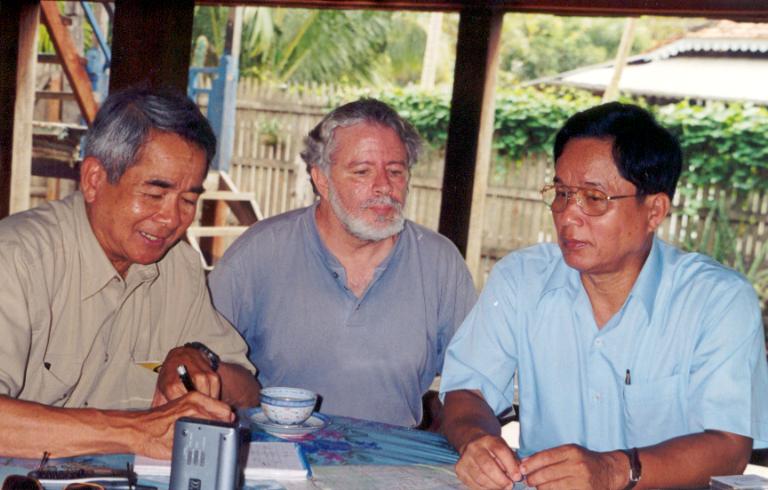

Photo - Left to Right:

Sos Kem, ZG, Pen Sovann

Pen Sovann, a former Khmer Rouge official, says the journalists were

held at the Kratie camp from 1970 until 1975 and then executed.

After Vietnam defeated Pol Pot forces in 1979, Pen Sovann became prime

minister of Cambodia and commanding general of the army.

|

Pen Sovann told us what he wanted to tell us and didn't go any further. He

said the XU camp was closed and the journalists were executed in 1975, when

the Pol Pot victory appeared imminent, and when Pol Pot began to purge and execute

the Hanoi Khmers. Prey Muth was executed in 1976.

I asked Pen Sovann why he hadn't disclosed his information about the journalists before. He said none of the Americans he had dealt with had asked about civilians, that they seemed only to be interested in military MIAs. He said he would have told them if they had asked.

After thinking about it, I decided that the matter was probably more complicated than that. Sovann asked me not to tell anyone what he said about the Sarys telling him about the newsmen. He hates Ieng Sary and his wife, who he believes ordered the execution of his older brother by having him buried alive. I don't think Pen Sovann was ready to reveal what he knew about the journalists while Ieng Sary and his wife were still leaders in the Khmer Rouge and undoubtedly able to have him assassinated. Now that they are under the Hun Sen government control (Ieng Sary and Hun Sen cut a deal in 1996), he is ready to settle old scores. He was too smart to think that I wouldn't reveal what he told me about the Sarys. In any case, I decided to see what I could get out of the Ieng Sarys themselves.

Interview with Ieng Sary and his wife Ieng (Khieu) Thearith February 5, 2001

LTG Pol Saroeun, chairman of the joint chiefs of staff of the Cambodian army, told Sos Kem that he would set up the interview for me with the Ieng Sarys but he was sure they wouldn't tell me anything. I didn't think they would either, especially if I went in and asked them directly about the journalists. They wanted to limit it to a half-hour but Sos argued for an hour, and that's what we got on tape, plus photos.

They started off by saying that his wife would translate from English in Khmer for him, because he had lost his English. When she saw that I was going to be a polite but aggressive interviewer (they were both visibly nervous about the interview), she told Sos that she couldn't keep up and that he should translate. He told me later that she had translated perfectly everything I'd said to that point, she just didn't want to do it. I then asked Ieng Sary a question directly in French and caught him off guard. He replied in French, and from then on we spoke a combination of French, English and Khmer.

Anyway, I got them to admit two things without their knowing why I was asking.

They confirmed that they were both in Ratanakiri province in July 1970, as Pen

Sovann said they were. Ieng Sary also admitted that he "greeted" the Hanoi Khmers

when they came back after the Lon Nol coup. But he said he didn't know Prey

Muth or anything about the journalists and the XU camp. He said, "Nuon Chea

will know about that."

Ieng Sary and his wife Khieu Thearith. Her sister, who

taught Sos Kem in the lycée, was married to the genocidal Pol Pot.

When I asked what subject she had taught him, Sos replied dryly: "Ethics."

She had a nervous breakdown, and Pol Pot divorced her.

I got Ieng Sary and his wife to admit to

a couple of facts without their knowing why I was asking. I didn't even

bother to bring up the missing journalists until the last ten minutes

of the hour-long interview. After we finished and were chatting informally,

she asked me for a printout of Part One of "The War and I," which I gave

her. I have a feeling she won't enjoy reading Part Two.

|

I believe it was as Pen Sovann said: The Ieng Sarys had responsibility in the

Khmer Rouge leadership for the journalists shortly after they were captured,

but then Sary became foreign minister, and it was probably Nuon Chea or Pol

Pot himself who ordered their execution after it appeared there would be no

value in holding them longer since they had won the war. In any event, Pol Pot

and the leadership knew exactly who and where the journalists were from the

beginning. Pen Sovann says the official line was that the journalists were CIA

agents but he didn't believe that and doesn't think the Ieng Sarys or anyone

else in the leadership believed it either.

Trip to Kratie and the XU Camp February 2, 2001

The police commissioner of Kratie had arranged, at my request, for me to interview two rice farmers from the village closest to the XU camp. I didn't like the way it started off because I had to give $50 to the police commissioner and ten dollars each to the two sources before I even talked to them. We had already visited the airstrip. I thought my 1973 source said the XU camp was in the northeast corner of the airstrip--and, indeed, we had found the remains of a camp there.

When the two sources told me that there was no Khmer camp in the northeast

corner of the airstrip, I argued with them and was ready to give up the interview

in disgust. In the spirit of proving me wrong, they said, no, that was the remains

of an old Japanese-built camp I had seen. The real Khmer Rouge XU camp, they

said, was in the northwest corner of the airstrip. It turned out that I was

confused. My 1973 source hadn't specified the location of the XU camp other

than to say it was at the edge of the airstrip. What he actually said was that

the journalists were held in a long narrow building in the "northeast corner

of the compound." Although only foundation remains are left, the camp was obviously

as my 1973 source described it, and the building had been where he said it was.

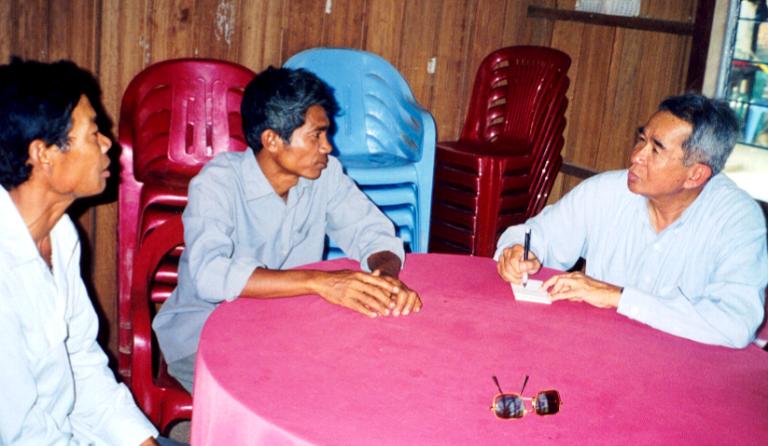

Sos Kem interviewing two farmers from the village closest

to the airstrip. They had firsthand knowledge of the camp where the journalists

were held. |

I asked to confirm the information about the XU camp with a village elder--someone

who wasn't a paid source and someone who wasn't expecting us.

Sos Kem is quite good at talking to all kinds of Cambodians--a little

to my surprise, I admit, since I thought he might be limited to Phnom

Penh-type people.

He did extensive interview work with refugees near the Vietnam border

in the '90s when he was assigned to the U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh.

Sos Kem confirmed through the village elder, 80, the details of the XU camp.

The elder said he did not join the Khmer Rouge but that he willingly cooperated

with them, and that both Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge soldiers used his home as

a billet. The Lon Nol government conceded the Kratie area to the Khmer Rouge

early on, and they hardly bothered to take security precautions. The 27 U.S.

military POWs who were repatriated at Loc Ninh, Vietnam, in 1973 after the cease-fire,

were grouped and held in the Kratie area. The preponderance of reports collected

by the DIA, CIA, and myself from 1970-2000 placed the journalists in the Kratie

area.

Alleged Gravesite

After we interviewed the village elder, Sos Kem stopped to chat informally with a group of men gathered in the social area under the stilted house. During the conversation, one of the men, Ban Peov, 39, volunteered the information that he had seen the bodies of ten or more people who were held and then executed at the XU camp during the period between 1973 and 1975. He could not pin down the date any closer.

Ban Peov saw the bodies from three long graves when they floated to the surface

during the rainy season (March-November). He was in the company of two Khmer

Rouge, one of whom later died in action, the other of natural causes. He was

between the age of 11 and 13 when he made the reported sighting. The Khmer Rouge

had come to put branches over the de-submerged remains, but didn't try to rebury

them.

Ban Peov says he saw the bodies of 10 or more people he believed to be "foreigners" who were held at the Kratie camp and executed between 1973-75. |

At first Ban Peov told us these were "foreigners" executed

by the Khmer Rouge. When we quizzed him closely, he backed off and said

that a Khmer Rouge cadre identified them as "intellectuals, important

people from Phnom Penh."

Whatever the case, the observation of the bodies obviously made an indelible

impression upon Ban Peov, for he led us without hesitation by motorbike

to the alleged site, which turned out to be approximately 200 meters north

and across Route 13 from the XU camp.

Ban Peov is a pleasant-natured rice farmer with seven years of schooling

and six children. Whether his information is correct or not, his sincerity

was unquestionable. He says he will be glad to cooperate with the JTF-FA

if any excavations are carried out.

Col. Chum Soyath of the POW/MIA Committee and Mr. Chong Seang Hak, police

commissioner of Kratie, were present during our interview, and can locate

the gravesite, which is easily accessible. It has been undisturbed in

the intervening years (it belongs to no one), and there are no mines or

other dangers in the area. I have passed on the coordinates of the gravesite

to the JTF-FA.

False Trails

Larry Humphrey was a U.S. Army deserter in Thailand who made his way to Cambodia.

Clyde McKay was one of two hijackers of a civilian freighter which he directed

to Sihanoukville. The Cambodians arrested both Americans after the Lon Nol coup

in 1970. They were first kept on a boat in the Mekong, but several American

antiwar activists passing through Phnom Penh from Hanoi protested their treatment,

and the government put them on loose house arrest.

Louise Stone--Dana Stone's wife--exchanged visits with them in Phnom Penh several times. They told her they wanted to join the Khmer Rouge as "freedom fighters." She told them about Dana Stone and Sean Flynn, and advised them to pretend to be journalists if they decided to escape their guards and leave for Khmer Rouge territory--which they did, in late 1970.

Reports shortly thereafter began popping up about two "journalists" being held in the area where Flynn and Stone disappeared. The DIA assumed they were Flynn and Stone. The two were executed after an escape attempt in February 1971. Their two Khmer killers later dug up their remains and tried to sell them to the Cambodian government for ten thousand dollars in gold. The government ran a sting operation and captured the men. They turned the remains over to the Americans but it appears the Central Identification Lab in Hawaii mislabeled them or for some reason never produced a conclusive report. One of the killers, I heard, is now mayor of a town in southern Cambodia.

British photographer Tim Page got the declassified DIA reports and traced Humphrey

and McKay to the general area of their burial site in 1991, and declared them

to be Flynn and Stone--case closed. The major--I'd almost say only--thing the

DIA team with the JTF-FA has done in regard to the journalists has been to prove

that Page's Flynn and Stone were actually Humphrey and McKay. I've got the DIA

report, and I talked to the DIA's Joe Fraley and Joel Patterson who ran the

investigation. They did good work and their conclusions are unassailable.

Recommendations

Ann Mills Griffiths of the National League of POW/MIA Families has been strongly behind our project from the beginning. I have known her for 30 years, and she is a longtime friend of Sos Kem. The Pentagon's JTF-FA professes to be happy that Sos Kem and I invaded their turf, as it were, and developed information--with a little luck that their staff of 455, with its annual budget of 55 million dollars, was unable to do after nearly ten years in Cambodia. Maybe so--and maybe there's a Santa, too.

Ann Griffiths has already made a strong push to have the JTF-FA excavate the possible gravesite. They have the personnel and equipment to do the job, and the site is easily accessible. If the JTF-FA drags its feet in this endeavor, Ann may need help in encouraging them to act. I told her I would try to rally the support of all of you, if it becomes necessary. And I'll let you know how it is going.

Notes

1. Our deal was that I would pay Sos Kem's full expenses and that he would

otherwise donate his time to the project. I hope to recuperate some of the costs

by writing about the trip. Therefore, I hope those of you who read this report

will maintain its confidentiality.

2. War Crimes Tribunal - There's a lot of talk about a war crimes trial for

the top leaders like Ieng Sary and Nuon Chea and Khieu Sampan. Although Hun

Sen and his government are bowing to international pressure and talking about

doing it, I don't think they are for the idea one bit. In fact, many people

still palpably fear the former Khmer Rouge leaders, including some in the government.

The government is going to try to stall the issue until it goes away or they

are all dead. However, they may get Ta Mok, Pol Pot's military commander, and

Duech, commander of the S-21 torture center--but I doubt even that.

3. We interviewed many more people than are listed in this account. This is

the gist of it.

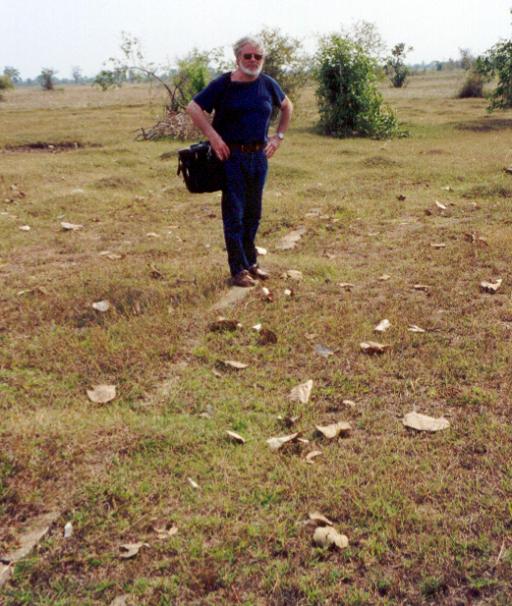

Zalin Grant standing on the foundation remains of the building where the captured

journalists were held in Cambodia from 1970 to 1975.

(Photo by Sos Kem— February 2, 2001) |

|