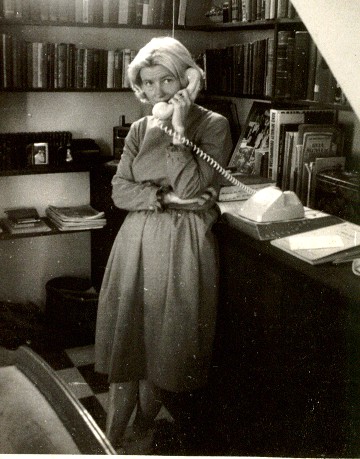

Claude in Spain at the time she was running a popular French restaurant. |

"Why did you stop including recipes with your Letters from a French

Village?" asked Henry, my old Paris friend and high-tech adviser,

when he was visiting us.

"I didn't really stop," I said. "It has been more like

a postponement. Doing a recipe takes me almost as long as writing a letter,

and I've been traveling quite a bit lately and just haven't had the time."

"Well, I think you should do it," Henry said. "It adds

something to your Letters."

I was considering what Henry said a few days later, when it suddenly

hit me: I already had some recipes that Claude had worked on years ago.

She did them in the late 1970s when we were in southern Spain, a few miles

up in the mountains from the Costa del Sol.

A friend of ours, Christine Goffin, had created a charming French restaurant

in the former stables of a Spanish farmhouse. La Chicharra had

a big fireplace in the main dining room and an outdoor patio overhung

with flowers. Christine's husband was transferred to Morocco for his work,

and she asked Claude if she would take over the restaurant for a couple

of years while she was gone.

Claude had always wanted to run a restaurant, and she jumped at the

chance. She turned La Chicharra into the most popular French restaurant

in the area. People drove their Rolls-Royces and Mercedes up from Marbella

to enjoy her wonder of a terrine, her steak au poivre, the best frites

in Spain.

During this period I had what I thought was a great idea. Claude would do a

cooking book but of a different kind than those being published. I would ask

her best friend in Spain, Mary Kennedy, an American freelance journalist for

the International Herald Tribune, to question Claude as they went over the recipes,

and I would tape-record their conversation. Mary Kennedy was one of the most

truly decent and generous persons we'd ever known. (She later died--much too

young--of a heart attack, and Claude was there to make the arrangements for

the family.) Mary was a connoisseur of French cheese and had certain specialties

she did well. But in fact Mary wasn't a very good cook. As I saw it, that worked

in her favor. She could ask Claude the kind of questions that many American

women would like to ask a successful French cook.

What a marvelous idea!

Claude didn't think so. She thought she was being asked to do the ABC's of

cooking. Instead, she wanted to do a book of recipes based on famous meals in

literature. This was a good idea too and later one done by somebody else. But

I knew if I got involved in that project, she would have me trying to correct

Moncrieff's translation of Proust, and I would have no time to do my own work.

So we hit an impasse. But I did get her to do a few sample recipes while being

interviewed by Mary Kennedy. They've never been published before, so I decided

why not?

French cooking basically breaks down into three elements. First, there is a

national core of dishes which practically every cook in the country knows how

to do. Then comes regional dishes, something maybe served in Normandy but not

in Provence, for example. Finally there is haute cuisine, more likely to be

found in restaurants than in private homes.

From my observations over the years, I had noted that a cook who didn't do

the national core of dishes very well was unlikely to succeed with the regional

dishes and certainly not with haute cuisine. To put it another way, if she couldn't

make a good salad or an omelette cooked to perfection, I suspected that she

wouldn't be able to handle a dish that called for sea urchins and foie gras.

So I wanted Claude to demonstrate how the national core dishes should be made,

starting with the simplest and moving progressively to the more complicated.

Making a salad sounds simple. But I can assure you, I've nibbled at quite a

few only out of politeness to my host. Ironically, the idea of having the cook

questioned by a straight man became the standard some years later for most cooking

programs on TV.

Sauce Vinaigrette

Claude: The sauce vinaigrette is our national salad dressing. The ingredients

are simple--salt, vinegar, oil, and pepper. But many cooks seem to develop a

mental block when they try to make it. The quality of the vinegar and the oil

is important. Pick up a supply of French wine vinegar, enough to fill a quart

bottle. After decanting into a clean bottle, add five small tarragon branches,

to give the wine vinegar a delicate perfume. Let it marinate for two weeks and

then pour though a filter into another bottle.

1 small pinch of salt

1 tablespoon of vinegar

1 pinch of pepper

3 tablespoons of oil

Dissolve a small pinch of salt into a tablespoon of wine vinegar by stirring

with a fork or a spoon. Add three tablespoons of oil and a large pinch of pepper

(or two complete turns of a pepper mill). Mix well. This is enough dressing

for four persons. Double the ratio for eight. Be careful to maintain the exact

proportions.

This is how Mary Kennedy, a freelance journalist originally from upstate New

York, did with a sauce vinaigrette:

Mary You said we can use any kind of oil and vinegar that is of good

quality. Does it have to be wine vinegar?

Claude Yes, it should be wine vinegar. The best comes from our city

of Orléans. It is imported to the United States. One should not have

any trouble finding it, particularly if you live near a city. The bottle should

read Procédé d'Orléans--made by the Orleans method.

Mary What kind of salad oil?

Claude Peanut and olive oil are the best. Peanut oil has no flavor and

should be used when you really want to taste the flavor of the vegetable you

are eating--the first spring lettuce, beets, rice, or potato salads. Olive oil--and

you should use a high-quality olive oil from Italy or Spain--is excellent when

you are preparing something such as a tomato salad, and it's especially good

when you use garlic. Two Mediterranean plants, we say, make a good wedding.

Mary Okay, I'm ready to try.

Claude Let's make the sauce vinaigrette directly in the salad bowl.

This is a trick my mother taught me, and it is solely for convenience. You can

make the vinaigrette in a separate container, if you wish, and pour it over

the salad at the last minute. One warning: Do not use a silver fork or spoon

to stir, because vinegar attacks silver.

Let's tilt the salad bowl a little and prepare the vinaigrette on one side.

First put in a pinch of salt, then a tablespoon of vinegar. Stir well with your

fork or spoon. Do this in the order I'm telling you, because salt doesn't dissolve

well in oil.

Mary I see.

Claude Now add three tablespoons of oil. Then put in a big pinch of

pepper. If you have a pepper mill, give it two complete turns.

Mary I keep stirring. Then what happens?

Claude Put some on your finger and taste it.

Mary But if I don't know how a good sauce vinaigrette is supposed to

taste, how do I know what I'm tasting for?

Claude You have a point. It's better that you follow my recipe for the

first couple of times. Then improvise to suit your taste. It should appeal to

your special palate. But be careful. We're dealing with small quantities. A

little added or taken away makes a subtle difference.

Mary It tastes strongly of pepper. The oil and vinegar are nicely blended.

Neither one seems to be dominant.

Claude The importance of the proportions cannot be emphasized enough.

You certainly don't want the vinegar to overwhelm your dressing. We have an

old proverb in France that says it takes four men to make a good salad dressing:

a miser for the salt, a wise man for the vinegar, a lunatic for the pepper,

and a profligate for the oil.

If you are serving fewer than three persons, simply take away a little of the

sauce after it is prepared. You want each leaf of your salad lightly coated

with dressing--but no more. Your salad should not be dripping.

Mary Kennedy in Spain at the time she and Claude were working on the

idea of doing a cookbook. (Right) Noël Kennedy, one of Mary's three

daughters (along with Kate and Elliot), visiting us on July 14, 2001.

|

Noël said to me at lunch one day, "You ought to get down on

your knees and kiss Claude's feet in appreciation for her being such a

good cook."

Noël is an American who teaches French to Spanish kids. We've

got some rather weird friends. |

Preparing Your Salad

Mary The sauce vinaigrettes I've done before tasted about like yours.

But they didn't come out that way when I served the salad. In fact, my salads

were sort of mushy and slick and unappetizing.

Claude Wait a minute, Mary. Tell me exactly how you make your salad.

Mary I wash the salad and dry it in paper towels.

Claude Oh, no. Don't dry your salads in paper towels. Use a clean kitchen

cloth if you don't have a salad basket. I use a salad dryer, which can easily

be found in the United States. It's a covered plastic bowl with a pull-string.

Put the salad in the bowl and pull the string a number of times. This spins

the salad, removing the water by centrifugal force.

Of course, you can easily find a wire salad basket if you prefer. Shake your

salad and leave it hanging for several hours until completely dry. Probably

half of all Frenchwomen still dry their salads the old-fashioned way--by putting

it in a clean kitchen towel, folding it like a knapsack, grasping the four corners,

and shaking vigorously till all water is removed. It's very important that the

salad be completely dry.

Mary Why?

Claude Because water on the salad dilutes the strength of the sauce

vinaigrette. As I said before, we are working with subtle flavors. Okay, then

what do you do?

Mary I cut my salad into the usual small pieces.

Claude Cut? Oh, Mary, never cut the lettuce or the leaves of any salad.

Break the leaves with your fingers. In France, we break the lettuce into pieces

four fingers in width and length. It doesn't matter if some leaves are larger

or smaller.

Mary After I prepare the salad dressing, I pour it over the top of the

salad, which I toss and place on the table for serving.

Claude I see the problem, Mary. Your procedure is wrong. Salads are

fragile, especially lettuce. The salad quickly begins to deteriorate in taste

after you pour the salad dressing over it. Above all, you want your salad to

be crisp and fresh when you eat it--not soggy and mushy. Here are the steps

you should follow:

Break and dry the leaves after washing. This can be done a few hours in advance

and the salad kept in a plastic bag. Then make the sauce vinaigrette--but not

more than an hour in advance of eating. Prepare the vinaigrette directly in

the salad bowl in which you will serve the salad. Then put the salad fork and

spoon face down and crossed like rifles over the vinaigrette. Now pour the salad

gently into the bowl and place it on the table.

Mary I don't toss it?

Claude Absolutely not. You'll do that at the table, at the moment you

are ready to serve it. In our best restaurants, the maître d'hôtel

brings the salad to the table at the last moment and prepares it in front of

you. Or as it used to be done in the nineteenth century, the elegant society

ladies would take off their diamond rings and toss it with their hands at the

table. I realize that most Americans eat their salad at the beginning of the

meal, but we usually eat ours after the main course, and I wish you would try

it this way while you are making French meals.

Mary Why do the French eat it in that order?

Claude It is said that it clears the palate. But I suspect that it is

simply a matter of custom. Why do Americans eat theirs first?

Mary Beats me.

Claude Anyway, put the salad near your plate at the table. When your

guests are ready for salad, then toss it. Many people, especially men, seem

to fumble with the salad fork and spoon. The important thing is to get them

to eat it quickly after you've mixed it with the sauce vinaigrette.

Mary What is the game French girls play when they toss the salad?

Claude Each leaf that falls from the bowl while they are tossing means

one year longer before they get married. If three leaves touch the table, they

won't get married for three years. It tends to make them careful when they are

tossing.

Mary I'll bet.

Claude By the way, in English you say "tossing." In French

we say "turning" or "moving." Either way, it is an important

procedure and something you should practice if you aren't adept at it. Take

a fork in one hand a spoon in the other and reach under the salad. Gently turn

it up and towards yourself in a flowing motion. Repeat this perhaps ten times

to make sure the sauce is well distributed.

Variations

I've given you the basic sauce vinaigrette. Here are a few variations:

Onion. When I buy the first lettuce of spring, I often add a few spring onions

to the vinaigrette. Finely chop the onions, including the green part, and put

it in the dressing. If you happen to like onions and can find the sweet Spanish

type or Vidalia, add an amount of onion to the vinaigrette any time you wish.

Mustard. Add one half of a teaspoon of Dijon mustard, which is imported from

France, to the vinegar of the sauce vinaigrette. Mix well. This is particular

good with winter salads, such as endives.

Garlic. Garlic and frizzy chicory have a love affair. Finely chop a small clove

of garlic and mash it well with a fork in the sauce vinaigrette. If you don't

want a strong taste of garlic, simply rub the sides of the salad bowl with a

clove of garlic and discard. A garlic vinaigrette goes well with a beet salad.

Dice the beets. Then mix the garlic vinaigrette and the beets an hour before

serving. Beets absorb vinegar, so you may have to add a little more before serving.

Also adjust for pepper and salt.

Lemon Substitute

Lemon juice can be substituted for vinegar in the sauce vinaigrette. If you

happen not to like vinegar, use lemon juice in the same proportion as I've listed

for vinegar, and adjust to taste.

Zalin After Claude read this, she and I had a little conversation.

Claude It's too long and boring.

Zalin We still disagree after all these years. I think some people will

read this and recognize their mistakes.

Claude Well, you should emphasize that Mary Kennedy and I were just

having a little fun.

Zalin So now it's you who wants to state the obvious. I think they can

figure that out. |