Robert was aflutter, nervous in that way a man gets when he thinks his wife

is about to do something foolish: I love her, but how will this make ME look?

Robert, I knew, was going to look like the lucky husband of a French model.

But Odile was a special kind of mannequin, and I understood his concern. I couldn't

help but smile, though, as he chattered on during Sunday lunch, before we left

for the fashion show, which was to be held at the exposition hall of a nearby

city.

Odile Langlois at home. The painting shows Odile operating on Manet's Olympia with the help of Robert, a work created by their friend Herman Braun-Vega. |

"I don't understand her," Robert kept saying. "Why does

she want to do this? Odile just doesn't give a damn what people think."

If anything, Odile's role as a model simply increased my admiration for

her. For in fact modeling is just her hobby. Her real job is a bit different--she's

one of the best general surgeons in our part of France.

When you consider that Odile began her medical training with a class

of 6000 and of the 625 who finally graduated to become doctors, only 25

were selected to become surgeons and of this number, only three were women--you

get the feeling that she has earned the right not to give a damn what

people think.

But giving a damn is what Odile is all about.

Her sister Françoise is a Catholic nun and I often say that Odile is

a nun too, a secular nun, a Mother Teresa with a scalpel. It's a description

that her three children, her husband, and my wife Claude--her close friend--say

is on the mark.

In an odd way, it was probably Sister Françoise who gave Odile the self-confidence

necessary to plow her way to the top of a male-dominated profession. Odile's

parents were members of the Resistance during World War Two. Her father had

escaped from a German prison camp, and her mother was arrested near the end

of the war when she was pregnant with Françoise. Prison conditions were

harsh and Françoise was born premature and sickly.

Because both parents worked it fell to Odile, who was born the following year

after war's end, to take care of her sickly sister as they were growing up.

Françoise was moved back a grade in order to be with Odile at all times,

since she found it impossible to ask the teacher for permission to go to the

restroom.

Françoise would whisper to Odile, and Odile would raise her hand: "My

sister requests permission to go pi-pi." By the age of seven Odile was

not only taking care of her sister but traveling around Paris on the métro

by herself.

Robert was wondering if it was proper for a surgeon to be

a model. My response: "Why not?" |

Odile's aunt was an operating room nurse during the French war in Indochina,

and Odile grew up hearing her mother and grandmother talk about this legendary

figure. Her aunt, Odile says, "seemed to me admirable, formidable."

At age fourteen, when French students then had to choose between majoring

in literature, math, or biology, Odile made her decision without thinking

about it.

It took a Bac (degree from the lycée) plus six years at medical

school to become a regular doctor. To become a surgeon, it was a Bac plus

thirteen. She became a titled surgeon in 1976, at a time when women were

making progress in France, yet still facing male hostility in medicine.

"Men thought women couldn't measure up to the hard work required,"

says Odile. "To put in a full day of operating and then to pull duty

surgeon that night performing emergency operations."

Instead of waiting to be assigned to an insignificant "woman's" post,

Odile knocked on the door of the chief of the surgical service at the hospital

where she hoped to work.

"I know you don't want women," Odile told him. "But I would

like to work in your service."

The chief was shocked by her boldness but impressed.

"Okay, I know you," he said. "You can have the position."

But this didn't mean she had suddenly become equal to the male surgeons.

"We women must never say we are tired. Men can say it but not us. When

we get pregnant we must never ask for favors. Above all you never ask to change

the schedule of duty surgeon."

Does such machismo still exist today?

"Yes. Women claimed equality. But we actually had to take it. Je m'en

fous."

Ah, maybe Robert is right, Odile really doesn't give a damn. At least for some

things.

It never bothered her, for instance, that many male patients were unable to

deal with the idea that a young woman was operating on them. She explained before

the operation what she was going to do, and they always nodded as though they

understood.

But after the operation came the inevitable question: "Where is the surgeon?"

"I am the surgeon."

A woman of humor and informality, Odile (rear) has an

easy working relationship with her surgical team. |

The patient would ignore her and turn to her male nurse to ask, "Doctor,

how did it go?" The male nurse, embarrassed, would look at Odile.

"Don't worry," she would tell him. "It's not important."

Although a practicing Catholic, Odile performed abortions early in her

career, when it became legal in France, because no other surgeon at the

hospital where she worked wanted to do it.

"For eight years," she says, "I did not take communion."

All in all, she considered it a positive experience in helping often

desperate women--sometimes wives who were pregnant, but not by their sterilized

husbands.

Instead of performing the abortion and moving on, as is usually the case with

doctors, Odile insisted that the women return in ten days for "post-operative

treatment." It was just a ploy to talk to them in calmer circumstances.

Some of them she sent to psychologists, others she put in touch with a priest.

When one man whose wife had ten children and four abortions demanded that she

remove the contraceptive IUD Odile had installed, Odile called him in and threatened

to sterilize him.

Since leaving the hospital near Paris, Odile has worked in the south, worked

in the north--and finally settled at the second largest hospital in the center

of France, which has 26 surgeons and 20,000 patients a year. She hopes to remain

here until the end of her career. (Of the 26 surgeons, three are women, the

other two gynecologists.)

It doesn't get any easier, she says. Often operating eight times a day, and

pulling emergency duty one weekend each month, she also shoulders a heavy administrative

load in her role as president of the hospital's medical board. She once had

to fight her way into a male-dominated profession. Now she has a decisive voice

in deciding which men will be hired by the hospital.

Nor does it get any easier for her on an emotional level. Odile has never developed

the hard carapace that protects many male surgeons. Not long ago she saved three

teenagers who were in an auto accident but the fourth and worst injured, a boy

of 16, died on the operating table.

Odile wept.

A Medical Interlude

Returning to the States several years ago, I happened to be watching a morning

television show hosted by Katie Couric. I was struck by the look in Couric's

eyes--the same look I'd seen in the eyes of young Americans in Vietnam after

a battle with heavy casualties. They called it the thousand-yard stare.

I asked my friends what had happened to her. Her husband Jay, only 42-years-old,

had recently died of colon cancer, they said. Since then Katie Couric has become

a leading advocate in the fight against colon cancer, even to the point of submitting

to a colon examination (called colonoscopy) on television, to try to relieve

people's fears about the procedure.

I have been very interested in Katie Couric's work, because colon cancer runs

in my family too. My dad, after surviving horrific combat in World War Two,

died at a relatively young age of the disease. So did his sister, my aunt. His

two half-brothers are colon-cancer survivors.

I have already had three colonoscopies, spaced over a number of years, all

performed in France. The French are some of the best in the world at preventing

colon cancer, with over a million colonoscopies carried out each year. In fact,

for overall health care, France is rated number one by the World Health Organization.

The United States? Thirty-Seventh. Think about that for a moment.

Odile knew that I usually had my examination done at a Paris clinic. But having

performed many colon cancer operations, she has her own ideas about how the

procedure should be carried out, and she suggested that I have it done at her

hospital. She wanted me to spend the night before the colonoscopy on her surgical

ward. Moreover, she insisted that I stay in bed at least four hours after the

examination.

This is a departure from the usual procedure, both here and in the States,

where it is carried out on an out-patient basis. But I remembered the last time

I'd had it done in Paris. Claude came to pick me up shortly after I had recovered

from the anesthesia, and we got caught up in one of those endless demonstrations

that go on in Paris, blocked in traffic for several hours. When I got home I

felt lousy. Odile meant to make sure that didn't happen to me again.

The first time I had it done I was a bit frightened. Hell, I admit it: more

than a bit. I was already middle-aged, and I was worried about what they might

find. When Andrée, my gastroenterologist, told me there was nothing,

I insisted that she tell me again, in five different ways.

I was still rattled when I started to leave. The nurses showed me photos taken

from the inside during the examination. I couldn't figure out what I was looking

at.

"Well, it's not your heart," one of them laughed.

Since then I've given a lot of thought about the procedure, so that I can try

to overcome the reluctance of friends to have it done. In fact, if you haven't

shown serious symptoms, abdominal pain or rectal bleeding for example, there

is almost nothing to worry about. (When my father complained to his GP about

abdominal pain, the doctor told him it was his "nerves" and made no

further examination.)

The problem starts with tiny growths called polyps which usually turn cancerous

over a number of years. If polyps are detected during the examination, the doctor

simply removes them. And that's that. The chances are about 90 percent that

the person will never develop the cancer, so long as periodic examinations are

continued. This is one of the most preventable of all cancers.

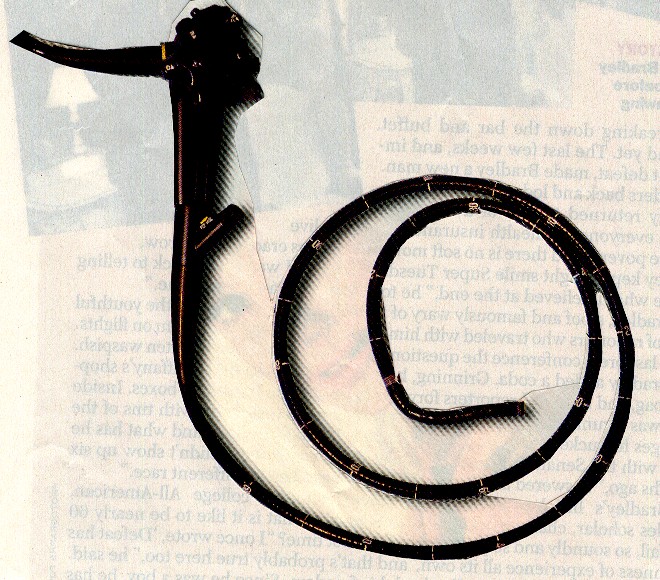

This is a "flexi-sig," the instrument inserted through

the rectum and into the colon. If the doctor finds any polyps, he snips

them out. The exam takes less than 20 minutes. |

The biggest problem with the colonoscopy is not the procedure itself,

which takes no more than 10 or 15 minutes and is painless under a short-lasting

general anesthesia. The problem is the psychology surrounding the exam.

For starters, most people don't like to talk about what is going on "down

there." And who relishes the idea of a small snake-like tube being

inserted into the lower third of the colon while the doctor looks at the

images produced on a computer screen?

There is also the matter of preparing for the examination. Which means

purging your system with an industrial-strength laxative. The laxative

powder is mixed with water. You drink two quarts (liters) over the space

of two hours in the evening starting about seven p.m. and two quarts the

next morning. Thus the examination is usually conducted in the early afternoon.

The clear liquid doesn't taste bad, doesn't taste good, just sort of

neutral. But you have to stick with it in order to finish it in the specified

time.

I find it is better to start earlier in the morning than later. I asked the

nurses to prepare the treatment for me to begin at six a.m., but they were changing

shifts at seven and didn't get around to it. That was my only complaint to Odile.

And you see, this is why she wanted me to stay overnight: you are close-by

to a you-know-what and alone to handle this bit of unpleasantness by yourself.

It marches through your system like Napoleon's army.

Such is my confidence in Odile that I didn't bother to ask who would be performing

the procedure. I knew she would choose the best. The week before I'd had my

blood test, an electrocardiogram, and chest X ray. Now that I had completed

the colon-cleansing treatment, I was ready.

They came for me at 2:10 p.m. and rolled me on a Gurney down to the basement,

where the operating suites were located. The team was waiting for me. The doctor

said hello and asked me several questions. "Why are you having this procedure

done?" Because colon cancer runs in the family. "When was the last

time you had it done?" Four years ago.

This is Odile and I just messing around--thank God! She came to the room as I was about to leave the hospital after my exam. I jumped back into the bed with my clothes on, and Claude took this snap. |

When I said, "Four years ago," the doctor said, "Parfait,"

and I knew I was in good hands. He was a Lebanese who had emigrated to

France twenty years ago, and we chatted a moment about the places we knew

in Beirut. Then I was asleep.

I awoke to the immensely reassuring words, "There was nothing. Come

back in five years."

I was back in the room on Odile's ward at 2:43 p.m. So 33 minutes had

elapsed from being rolled out of the room to being rolled back in, and

that included a few minutes of holding time outside the operating suite

where the procedure was done, as they monitored my vital signs to make

sure everything was okay.

I felt so well that I tried to leave before 6 p.m. But Odile had guessed

that I would try to do that. She ordered the nurses not to remove the

taped catheter from my right forearm--the insertion point for the anesthesia

drip--until exactly six.

Now, I have related this medical interlude for only one reason.

For you.

I'm telling it to you straight. From the moment you make the appointment until

it is over you are going to have some psychological worries. But it is just

a bump in the road. And we want it to be a long road.

Trust me on this. Go get it done.

The Fashion Show

Odile Langlois the Model

I was surprised by the size of the crowd. There must have been several thousand

people inside the exposition hall. Booths were set up to cover every conceivable

aspect of getting married, from buying a gown to planning a honeymoon on an

exotic island. Odile and the rest of the models were to show clothes that would

be chic for members of the bride's and bridegroom's families to wear.

Robert and I wandered around the hall. He was still uncertain about Odile's

role in the show, but both of us were pleasurably distracted by the stunning

array of pretty young women at the exposition. This being about marriage, there

was, of course, a higher percentage of girls than guys.

As a matter of fact, we were so intrigued by the whole affair that we arrived

late at where the fashion show was to take place. All the seats were taken and

people were crowding around the elevated platform at the end of the catwalk.

I had to elbow my way into the crowd to find a decent spot where I could take

photographs.

At three-fifteen the show began to the music of Orbison's "Pretty Woman."

The 18 large-size models began to appear, the audience applauded wildly. When

Odile arrived on the platform I raised my camera and yelled "Odile! Odile!"

as though I were a fashion photographer at a Paris showing of Dior.

Odile was radiant. She had a new hair style, and her makeup had been expertly

done by Marie-Neige, who is also a friend of Claude's. She was as confident

as any of the world's supermodels, if not exactly a size four.

Odile gave me a smile and a look that said, "Aren't we having a little

fun?" Even Robert had finally begun to relax.

The entire show went very well. And I was pleased that my friend Robert came

off looking so good.

Odile (right) and the other models parade as a group at the conclusion

of the show--to much applause. |

|

Free hairdos were offered at the

show. Whatever their size, the French

certainly have style. |

Recipe Six

Robert's Salted Pork and Lentils

Robert usually does the cooking since Odile has very little free time. He is

good in the kitchen, although I don't think he would describe himself as an

outstanding cook. But he is smart enough not to try to get too fancy. On the

day of the fashion show he made lunch for the two of us, and it was one of my

favorite dishes--a petit salé, salted pork, in this case cooked

with lentils. Salted pork is one of the basic French dishes which is known throughout

the country. For some reason, it doesn't seem to be widely available in the

United States. But you can make your own. Or as Elizabeth David advises, you

can use unsmoked bacon in its place.

|

| Left to Right - Claude, Robert and Odile at one of our

typical dinners.Odile doesn't smoke or drink, not even a drop of wine. Robert and I don't smoke either. As for drinking

wine, well, no comment--although we are drinking apple cider from Normandy at this particular dinner. |

If using salted pork, wash it carefully to remove the excess salt.

Place the pork in a pot and pour in enough water to cover it. Add a bay leaf, a sprig of thyme, one onion, a big carrot cut lengthwise in four slices, a clove of garlic, a small stalk of celery with its leaves, and two or three sprigs of parsley, including the stem.

Bring the water to a simmering point. When the scum starts rising, skim it off. Bring to the point of slowly boiling for an hour.

Rinse the lentils (80 grams person), drain, and put them in cold water. (Lentils should always be started in cold water.) Bring the lentils to the boiling point. Then strain the lentils and add them to the pot with the salted pork. Cook for 25 minutes more, tasting at intervals, for the lentils should not be overcooked. If possible use lentils du Puy.

Serve the pork surrounded by the lentils.

|