Louise Stone was a determined woman. She spoke quietly and appeared calm. But I knew she was roiled by an inner turmoil. There would never be another man for her but Dana—lumberjack, male model, gold prospector, merchant marine—and, finally, war photographer.

She thought he was invincible. It never occurred to her that something like this might happen. She was at a hotel in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, waiting for him to return from filming a battlefield scene for CBS. He and Time photographer Sean Flynn, son of actor Errol Flynn, were covering the story on motorbikes. They were captured on a road near the Vietnam border, April 6, 1970. Dana was wearing a braided necklace from Louise’s hair.

When I arrived in Saigon on April 19, 1970 to investigate Flynn and Stone’s capture, she hugged me tightly. Resting her head on my shoulder, she said, "I'm so glad to see you. You can do this, I know you can."

"Maybe I can figure out what happened to them," I said. "Beyond that, I'm not sure I can do anything."

"I've got to get Dana back," she said. "I'll do anything. Just tell me what I should do."

Yes, Louise would do anything. She was fearless. And that worried me. I could only stay a month or so to run the investigation, which Time and CBS had asked me to conduct, probably because I had done my military service in Vietnam as an army intelligence officer. Then I had to get back to my writing job at The New Republic in Washington.

"You've got to be careful," I told her. "All kinds of rumors are going to pop up. You can't go for them.”

Dana Stone’s Last Letter

From 1969 to March 1970 Louise and Dana, my companion Susan and I, had been on separate drives overland in VW campers from Singapore to Paris. We ran into each other once near Mount Everest but otherwise kept in touch by mailing letters in care of U.S. Embassies along the way. We all agreed before leaving Singapore that we were finished with the war and would never return. But when I reached Paris Dana’s last letter was waiting. They had gone back.

"Louise is here now, sitting with me at the 15th Aerial Port in Danang, waiting for flight 640 to Saigon, already 2 fucking hours late and it's raining. So there are NVA troops and trucks in the Ashau again. But the U.S. doesn't want to go in and the GVN won't. Ben Het had 7 arc lights around it two days ago and it looks as if the 4th will move east out of the Highlands to avoid getting involved. More and more Vn talking about how it would be to live under communism. . ."

No one should try to figure out what makes a couple’s relationship work. But if anybody wanted to give Dana and Louise a shot, theirs made for a Rubik’s Cube of psychology.

He was one of the most gregarious and upbeat guys I’d ever known, a devoted practical joker who couldn’t sit still for five minutes. She could read for hours without moving. His major was world curiosity; hers was art history. Both of them liked to live close to the ground, frugally, without pretension, the more physical hardship the better—and maybe that was the answer. Yet even that seemed a bit odd, since she was the daughter of a Mercedes-driving Kentucky doctor and he had attended boarding schools in Vermont.

Whatever the ingredients that went into it, their relationship worked: Dana and Louise were inseparable. She took the gold nugget a miner had given her during Dana’s prospecting days in California and turned it into a wedding band.

Their marriage was sometimes tumultuous. But out of that came a stronger love. She began to read to him as he worked, softening his anti-intellectual pose. Of Mice and Men made him cry. When I brought her a pirated copy from Taiwan of the just published Couples by John Updike, he wanted to read it first.

Looking for Dana

I tried to keep her mind off his capture by keeping her busy. I asked her to help me create bio sheets with photos for all the missing journalists. We passed them out to everybody involved in the war, even sent the flyers to the North Vietnamese at the Paris peace talks.

Then I asked her to contact various people while I ran the investigation with the help of a Vietnamese intelligence officer Nguyen Tri Tong. We learned that Dana and Sean had been captured by elements of the VC and NVA at a long-established communist checkpoint on a road near the Vietnam border.

|

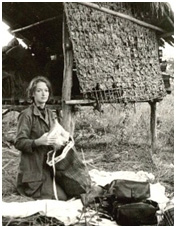

AP photographer Dana Stone

Vietnam 1968. |

|

|

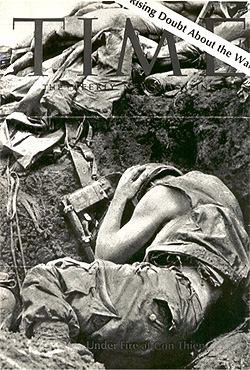

Dana Stone’s photo of Marine under rocket fire used as a Time cover—1966. |

|

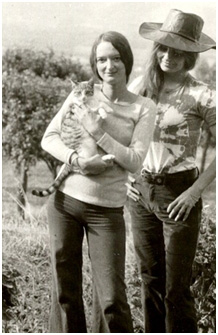

Louise Stone camping in Laos with Dana—1969. |

That seemed about all we could do at that point. So when I got ready to leave Saigon, I suggested that Louise return to Cambodia and pass out the biographical sheets of the missing journalists to military and civilian officials in Phnom Penh.

This proved to be a big mistake. Trying to save her husband, Louise fell into two adventures in Cambodia that led to the killing of two Americans and a Dutchman.

The Boat Hijacker

The first began three weeks before Dana disappeared, when Clyde McKay hijacked a military transport ship that was headed to Vietnam. He diverted the ship to Cambodia and arrived March 17, 1970. McKay and his fellow hijacker, Alvin Glatkowski, were treated as celebrities for a few hours. But next day the American-backed General Lon Nol overthrew Prince Sihanouk as head of state, and he promptly tossed them in jail, where they were joined by Larry Humphrey, an army deserter from Thailand.

McKay and Humphrey began planning to escape after they were later placed under loose guard in a hotel until their case could be resolved. Glatkowski, who had suffered a nervous breakdown, wasn’t included in the plot.

Louise talked her way past their guards and went to see McKay and Humphrey, thinking they might be able to help in some way with the missing journalists. She discovered that they considered themselves “revolutionaries” and wanted to join the North Vietnamese Army.

“I told them all about the journalists who were missing,” Louise wrote me. “When they said they planned to escape, I told them how easy it was for press people to get through Cambodian roadblocks, and suggested if they could get a car to try that.”

A few days later McKay and Humphrey escaped. Glatkowski turned himself in to the U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh. He eventually stood trial in California for treason, kidnapping and piracy, and was sentenced to ten years in prison.

Soon after McKay and Humphrey disappeared, Cambodian intelligence officials got in touch with Louise and told her they had picked up reports of two “journalists” who were seen in Kampong Cham Province.

“I realized that General In Tam and the Deuxieme Bureau of Kampong Cham did not know who these two Americans probably were,” Louise said, “and I thought it best not to tell them.”

Thus began the confusion about McKay and Humphrey which would last for the next 30 years. They claimed at first to be “revolutionaries” but when the Khmer Rouge didn’t buy that story they “admitted” they were journalists. Neither of them claimed to be Sean Flynn or Dana Stone. That was simply a mistaken assumption churned into the system by American newsmen and the Pentagon.

In fact, after McKay and Humphrey were killed by the Khmer Rouge in February 1971, the Pentagon ruled they were Flynn and Stone and declared the case closed. That remained the official U.S. position for the next 15 years, until a DIA agent collected evidence showing that a mistake had been made—it was McKay and Humphrey, not Flynn and Stone.

Later, Tim Page, a former photographer in Vietnam, went to Cambodia and declared that he had found Flynn’s remains. The Pentagon’s Central Identification Lab established through DNA testing in 2003 that Page had found McKay.

The Traveling Dutchman

Louise, of course, knew all the time it was McKay and Humphrey. And she quickly jumped to another project to save her husband. This one involved a young Dutch traveler named Johannes Duynisveld, who had been in Bolivia at the time of the CIA hunt for Che Guevara and considered himself a bit of a revolutionary, too.

Hans Duynisveld had entered Cambodia from Thailand near Siem Reap with the intention of visiting Angkor Wat. When he set out for the temples by foot the next day, June 19, 1970, he was wounded in a mortar attack and captured by the North Vietnamese. He was released August 24, 1970, along with two journalists.

The Honorary Dutch Consul in Phnom Penh, an Italian who spoke no Dutch, quickly arranged for him to fly from Bangkok to Singapore, where he was expected to continue his round-the-world trip. But Singapore refused him entry because of his hippie looks and lack of money and shipped him back to Bangkok.

At that point Duynisveld got in touch with a political officer at the U.S. Embassy in Bangkok and told him he had seen Dana Stone at the North Vietnamese field hospital where he was treated for his mortar wounds. Dana, he said, had been wounded by a Chinese grenade and needed medicine desperately. Duynisveld said his NVA captors had told him he could reveal the information about Stone and possibly help free him and six other journalists.

The story Duynisveld told was filled with such precise detail that the French ambassador to Phnom Penh and a number of seasoned American journalists later said they found Duynisveld very credible. The State Department got in touch with Louise and told her his story about Dana. She flew to Bangkok to meet with him. The first thing he said to her was, “Your husband is alive.” He identified Dana from a photo and described him to Louise’s satisfaction.

Louise was not a credulous person. After she graduated from Randolph-Macon College she traveled around the world. We had met plenty of guys like Hans Duynisveld. It was a time when anybody could hitch cheap transportation overland between Europe and Asia. And both of them being travelers, they got along well.

“When I was with Duynisveld I tended to believe him,” she wrote me. “When away, it all seemed so fantastic, so impossible. I expected maybe never to see him again, or that he would request money, or some kind of deal.”

But he didn’t. He told her if she would buy some medicine, just enough to replace what the NVA had used to treat Dana, he would take it to communist territory and bring out her husband.

The political officer at the Bangkok embassy, who I thought was probably CIA, met with Louise and Duynisveld and later said, “He seems to have no ulterior motives. He hasn’t tried to sell his information, and he’s possibly legitimate.”

Arthur Dommen, a respected journalist for the L.A. Times, thought so too. Dommen became head of the Committee to Protect Journalists in Phnom Penh, after numerous international journalists were killed or captured on Cambodia’s roads. It was the only way they could cover the war in Cambodia, since no helicopters or planes were available, as in Vietnam.

CBS also gave its full support to Duynisveld’s mission. After Duynisveld left for communist territory, CBS headquarters in New York asked Robert Lorentzen, who was involved in the mission, for a detailed report.

Lorentzen wrote an 11-page memo that ended with a question: “In summary, should Louise, and in turn CBS News, have supported the Dutchman’s attempt to return to the other side and gain release of Dana Stone? An unqualified ‘yes.’”

Lorentzen speculated about Duynisveld’s possible motives. “In the beginning the Dutchman may have just been looking for money,” he wrote, “but after more than two weeks of association with Louise Stone he could have been converted to her cause. Louise is a very honest, straight-forward, sincere woman and I doubt many people could spend two weeks with her and not want to go out and search for her husband. Two days with her in Phnom Penh and I had thoughts of returning to Saigon via road—to search for signs of Dana and Dutchman.”

At 7:00 a.m., Tuesday, September 15, 1970, Arthur Dommen picked up Duynisveld at his hotel and drove him to a ferry-crossing outside Phnom Penh. This was the route to communist controlled territory. Dommen had bought him a bicycle. Duynisveld gave Dommen letters to be mailed to his mother and girlfriend in the event of his death. Then he rode off.

No problem in my long investigation into the capture of Sean Flynn and Dana Stone gave me as much trouble as trying to sort out the truth about Duynisveld. As an intelligence officer and then as a journalist who had interviewed thousands of people, I had met all kinds of liars and deceivers.

But it took Duynisveld’s death for me to reach a conclusion about his story, which ended as incredibly as it began.

The Dutch Guerrilla

On his third day of biking to guerrilla territory, Duynisveld stopped when two shots were fired in his direction. The Khmer Rouge arrived and took him to a recently bombed village. He asked them about the missing journalists. They said they had no information. He continued to ask about the newsmen every day, in the manner of someone stopping a passerby on the street. Everybody said they knew nothing about it, the journalists were probably dead, and Duynisveld accepted what they told him without further question.

The rough life of the guerrillas didn’t bother Duynisveld. Even the nightly bombing failed to rattle him. When a cobra suddenly slithered from the jungle, the Cambodians ran in fear. Not Duynisveld. He caught the snake. He skinned and cooked it and shared the meal with them. The Khmer Rouge were impressed by this Dutchman.

Most important, as they saw it, he had a valuable talent. He was a good mechanic and handyman. After he fixed their motorbikes and radios, they took him to a broken-down jeep. If he could repair it, they said, it was his to drive. It took him two days but he got it running.

On November 26, 1970, they sent him to a training camp and gave him an AK-47 rifle. Later that day 40 Viet Cong soldiers came by to congratulate him. He had been inducted into the guerrilla army. The next day he went on his first operation. By early December he had become a hardened guerrilla fighter.

On December 19, 1970, Johannes Duynisveld and his Khmer Rouge unit walked into an ambush laid by South Vietnamese troops near the Cambodia-Vietnam border. Duynisveld was killed instantly by small-arms fire.

Duynisveld had kept detailed journals during his travels. With the help of the State Department, I got the diary he had kept during his first captivity as well as the one he wrote until two days before his death. They indicated that he had made up the story about seeing Dana Stone. He had pulled the names of the journalists from an article published in a French-language paper in Phnom Penh shortly after he was released in August.

His motivation seemed to involve a girlfriend in Holland who had jilted him. He described the broken engagement as the worst thing that had ever happened to him. In looking for the newsmen, he thought he might gain some publicity that would impress and make her reconsider. After he became a guerrilla, he wrote:

"I can’t get to sleep for the first couple of hours, so then I think about Marian. If she hadn't broken our engagement, I wouldn't be here. But, well, I'm here anyway. So I have to make of it what I can." He hoped she would say: "'Yes, Hans, I have made a mistake and I want to make up with you and let's start over.'”

I traveled to Holland to talk to his parents, to neighbors, to anybody who had known him. Everybody’s take was the same. Hans Duynisveld was a good-natured young man, poorly educated and naïve, but well liked for his generosity in helping the neighborhood children.

The Duynisveld affair and his death pitched Louise into despair. I began thinking about how I could get her to leave the war—before she got killed or maybe someone else did too. My worry for her was constant. But she wasn’t ready to give up.

Intel Agent

Louise was becoming an accomplished intelligence agent. She had won the confidence of the Cambodian Deuxieme Bureau. They routinely showed her the intelligence reports they had picked up. U.S. Military Intelligence presented a tougher problem. But she began to cultivate the younger enlisted agents in the 525th MI Group in Saigon. Soon, she was calling them “my boys.”

Her boys secretly gave her classified documents concerning prisoners of war. One of their sources was a North Vietnamese defector who claimed to have seen six journalists in Cambodia. She asked the head of MI for permission to talk to the source. He turned her down. She then wrote to General Creighton Abrams, commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, and he ordered Military Intelligence to let her interrogate the source.

Her interrogation, which lasted three hours, would have shamed many career intelligence officers. It was conducted professionally and her report was written better that dozens of classified DIA documents I’d read. She was careful not to suggest the information she received was anything but from a North Vietnamese source of unknown credibility who had, however, already passed a lie detector test.

The source’s claims coincided with the information the South Vietnamese intelligence officer and I had collected shortly after the journalists disappeared. The source had seen six journalists outside Kratie City in May 1970 and his description of one of them fit Sean Flynn. Louise had done good work and it left her optimistic. She believed Dana would be eventually freed.

Spain

This was a good moment, I thought, to get her out of Indochina. My worry for her had continued to grow. But how to do it without making it sound like I was suggesting she should give up? I sweated over the letter, it took me a long time to write. She had put in so much effort and actual risk to her life to help Dana. I told her she had done all she could right now and would have to wait for changing developments to do more.

We asked her to come to the south of Spain where I and my wife, Claude, had settled. Reluctantly, she finally agreed. Claude found her a small house in an orange grove 300 meters from where we lived, in the hills above Malaga. Her radio was always on and tuned to BBC News. She had a bag packed and was ready to leave minutes after she heard he had been released.

|

Louise Stone (left) and my wife Claude in Spain—1973. |

|

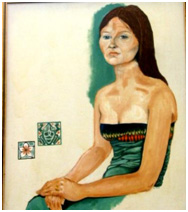

Louise had studied art and painting. She was talented at handicrafts such as book binding and jewelry-making. At first she kept busy and even resumed painting. But when she did Claude’s portrait everybody realized that she had painted her own ineffable sadness into Claude’s face.

Slowly, she began to withdraw and was seldom seen in public. Only visits by young John Steinbeck’s companion, Crystal, and Dana’s brother, Tom, seemed to cheer her up.

One day when I went to see my British friend George Sturrock at the second-hand bookshop in Torremolinos, Louise happened to be there looking for something she hadn’t already read. I walked over and stood beside her, so close that we were almost touching. She said nothing.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

She turned in surprise. “Oh, I didn’t see you. Something is wrong with my peripheral vision.”

I later read that the loss of peripheral vision was one of the early signs of multiple sclerosis.

After her disease was diagnosed, she returned to her home in Kentucky. She withdrew from most social contact, as the MS grew progressively worse, and was unable to write. She died in March 2000, at the age of nearly 60.

|

When Louise did my wife's portrait, she painted her own sadness onto Claude's face. |

A lot of wives of U.S. military prisoners of war in Vietnam had tried to help bring about the release of their husbands. But no one had done more than Louise Stone. I was right. Dana was the only man for her. And I believe she died from a broken heart as much as anything else.

|