By Zalin Grant

1. “The Yankees Are Coming!”

I was born and raised in the first town in the South to secede from the Union. Our people had played a big role in starting the Civil War. One of our lawyers had drawn up the Articles of Secession. And in early 1865 General William T. Sherman was out to make my hometown of Cheraw, South Carolina pay for what it had done.

Sherman had fooled everybody. Charleston, on the coast, had been under siege for four years and stood as the South’s symbol of rebellion. Sherman was believed to harbor a special hatred for both the state and the city. A Charleston belle had jilted him when he had served as an artillery lieutenant at Fort Moultrie, South Carolina, at the start of his career. Or so it was said.

Surely, Sherman would be itching to destroy Charleston after he left Georgia. Everybody believed it. So they fled with their most valuable possessions. Cheraw (chu-raw), which was named for a Cherokee tribe, was a favorite destination because it could be reached by train and seemed like a suitably out-of-the-way hiding place. It was located mid-state, near the border between South and North Carolina.

Suddenly, this town of four thousand became the hiding place for the huge cannons that had successfully defended Charleston. Train cars filled with food and ammunition, with paintings and carpets, wagonloads of wine, arrived every day.

Then came the astounding news. Sherman wasn’t going to attack Charleston, after all.

He was going to attack Cheraw!

|

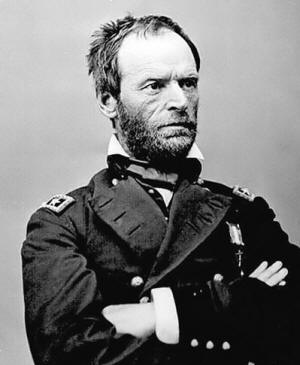

| General Sherman was a living devil to us growing up in the 1950s. |

He had turned from Savannah and marched toward Columbia, the capital at mid-state. That put him on a direct path to my hometown, 70 miles away. He intended to cross the Pee Dee River at Cheraw and ravage North Carolina and then Virginia.

The cry went up: “The Yankees are coming!”

When his troops attacked Georgia they had destroyed homes and towns almost in a routine way, without much passion. Their attitude changed when they entered South Carolina.

“In our march through South Carolina every man seemed to think he had a free hand to any kind of property he could put the torch to,” one of Sherman’s soldiers wrote. “South Carolina paid the dearest penalty of any state in the Confederacy, considering the short time the Union Army was in the state.”

On March 2, 1865, Sherman received a dispatch from General Oliver Otis Howard, his 17th Corps commander, telling him his troops were just a short distance from Cheraw. Their objective was to capture the river bridge.

As they approached Cheraw from the west they ran into heavy fire. The Confederates were trying to buy time while their troops soaked the bridge with turpentine. They retreated at the last minute and succeeded in burning the bridge. This meant Sherman had to layover in Cheraw until his engineers could arrange a makeshift crossing.

On Friday, March 3, 1865, Sherman, accompanied only by his staff, entered Cheraw in a drizzling rain. He liked what he saw. He ordered guards placed around the town’s many lovely houses. His men needed a break. This was a good place to give them a couple of days of rest. He set up his headquarters four blocks from where I lived.

Generals O.O. Howard and Francis P. Blair had already taken over one of the town’s most luxurious mansions. They invited Sherman to lunch. Blair had confiscated eight wagonloads of Madeira wine that had been shipped from Charleston cellars. He spread a dozen bottles on the table with the bountiful food.

Sherman called it, “The finest Madeira I ever tasted.”

The lunch in Cheraw was to stand as Sherman’s only victory celebration. Under the influence of the Madeira, one of his generals jumped up with a violin and began to play and sing. Another recited the doggerel he had written, called “Sherman’s March to the Sea.”

Sherman claimed never to have taken part in the looting carried out by his men. But after such a fine lunch he could not resist. Blair showed him some exquisite carpets they had confiscated, and Sherman told his orderly to take them. They were made into saddle bags and blankets and a rug for his tent.

Sherman captured enough food and supplies in Cheraw to fill every wagon of Howard’s 17th Corps and part of Blair’s 15th Corps. His troops didn’t need to forage for food, but they did, carting off everything they found, sometimes burning it. More of Sherman’s troops passed through Cheraw than any town in the South.

So much ammunition and explosives were found that he ordered it to be hauled away and buried in a ravine outside town. A guard was posted to keep anyone from smoking. But the site was too volatile. A massive explosion suddenly hit the town like an earthquake, breaking windows and killing several people.

Sherman believed rebel troops had set it off. In a fury, he threatened to burn every building in the town. He calmed down after his staff persuaded him it had been an accident.

On Saturday, March 4, 1865, Sherman gathered his troops for a celebration. Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration was taking place in Washington. Sherman ordered that the 20 huge cannons which came from Charleston be lined up on the field and overloaded with gunpowder.

Abraham Lincoln made one of the most memorable speeches in American history:

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

Sherman made a calculation of the time Lincoln would probably finish his address. He set that as the moment to fire the overloaded cannons one by one. The explosions provided a tremendous salute to the president, while at the same time destroying the big guns, a symbol of the defeated Confederacy.

After the celebration Sherman’s troops headed to the Cash plantation outside Cheraw. Colonel EBC Cash was on their target list, and they intended to kill or capture him. Cash was the largest plantation owner in our area, with 200 slaves and 8,000 acres. He had commanded the 8th S.C. Volunteers at the first battle of Manassas, where he captured a Yankee congressman, and helped defeat a Union brigade commander named William T. Sherman.

But Ellerbe Cash was nowhere to be found.

Dr. John Bachman, minister of the Charleston Lutheran Church, had accepted Colonel Cash’s invitation to take refuge on his plantation. Bachman had given the invocation at the Secession Convention in Charleston in 1860, and his friends feared that he was on Sherman’s reprisal list. He was a well-known naturalist who had worked with John J. Audubon.

When news came that Sherman was headed to Cheraw, Bachman volunteered to stay with the women at the plantation while Cash and the other men hid in the swamp. Bachman’s account of what happened on that March day in 1865 was included in the memoirs of Jefferson Davis.

|

| Rev. John Bachman was a naturalist and founder of Newberry College in SC. |

Union Troops arrived at the Cash plantation in different groups. They filled all the plantation's carriages with plunder from the Big House. Smoke houses were emptied, every chicken stolen. The blacks had put on their best clothes in anticipation of greeting their liberators. But the Union troops beat and robbed some of them and stole their clothes and shoes. They tricked black women, promising them silk dresses they had taken from whites, and then raped them.

Sherman had given orders not to burn occupied houses. So the troops drove residents away and then lit the houses with turpentine-soaked cotton. By evening the whole area was ablaze. Several hundred troops gathered at the Cash plantation, waiting for his house to go up. They cheered when a torch was put to an outbuilding and the fire began to spread.

A Union captain suddenly appeared and climbed to the roof of the main house. Bachman and the women passed him wet blankets. He called on his company to douse the flames using water from a nearby well—which, to Bachman’s surprise, they cheerfully did.

The house was saved but Bachman was taken to the back of a stable and threatened with death if he didn’t reveal where the money was buried. The Federals said they had heard that Cash had a hundred thousand dollars in gold and silver on the plantation. When Bachman said he didn’t know anything about it, a lieutenant kicked him to the ground.

“How would you like to have both of your arms cut off?” the lieutenant asked.

He brought his sword down on Bachman’s left arm, breaking it.

Bachman’s daughter rushed from the house to his side. “You dare not murder my father,” she said. “He has been a minister in the same church for fifty years, and God has always protected him.”

“Do you believe in a God?” the lieutenant said. “I don’t believe in a God, a heaven nor a hell.” He made her strip to see if she was hiding any valuables under her hoop skirt.

Incidents like this were taking place all over Sherman’s march through South Carolina. Of course not all Union troops were set on punishing the state. Doctor E.P. Burton, surgeon of the Seventh Illinois Regiment, left an account of his tour of Cheraw on Sunday, March 5, 1865.

“Cheraw was a very pretty town of some three or four thousand inhabitants,” he wrote, as he stopped off at St David’s Episcopal Church. But when he returned to the town later in the evening, he found that all the stores had been burned. “Vast clouds of dense smoke were arising from burning buildings and hung around the town in a mournful grandeur.”

As he left town with the troops next morning, Burton wrote, “I am getting about satiated with burning.”

After Sherman crossed the Pee Dee and drove into North Carolina, he ordered the burning and pillaging stopped. The state was damaged, swaths of pine trees were torched, and Fayetteville suffered. But North Carolina and Virginia escaped the kind of destruction that took place in South Carolina. Sherman had accomplished what he set out to do.

He had crushed the Cradle of Rebellion.

The war ended 35 days after he left Cheraw. General U.S. Grant met with General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox in Virginia to accept the surrender.

2. The Lost Cause

Cheraw had capitulated. But in the minds of the town, it did not surrender.

The South would rise again, everybody declared. My teachers admonished me if I referred to the Civil War. It was the War Between the States. It had nothing to do with slavery. The war was about State’s Rights. We had been treated in a manner both malicious and unconstitutional. General Sherman was a living devil to us. He had fired our town and ransacked our library.

As Cheraw was the first town to go to war, it also became the first in the South to erect a monument to the Confederate fallen. The dedication took place on May 10, 1867. This was an act of stubborn defiance. The town was still under the bayonet-rule of Federal troops when the monument was raised right under the eyes of Yankee soldiers who thought it was just another burial plot.

Every Tenth of May, with my schoolmates, I marched to the monument, which stood in the tree-shaded cemetery of St David’s Episcopal Church. This was our hallowed ground. The church, built in 1769, had been used as a British hospital during the Revolutionary War.

We gathered at our school for the mile-long march. We boys wore our Sunday best and the girls, dressed in white, carried red roses to sprinkle on the graves. We marched to St David’s behind the mournful sound of muffled drums. A color guard bearing the shot-tattered flag of the Eighth South Carolina Volunteers and the Stars and Bars of the Confederacy led us on.

When we reached the cemetery, speakers, honored guests, and a choral group took their places around the white marble obelisk, which bore the words: “Brave heroes slumber here. Loved, and honored, though unknown.”

|

St David's Episcopal Church--Cheraw SC.

(Photo David McCall--2009) |

The ceremony was highly charged. The speakers emphasized the heroic triumphs of our soldiers and their tragic deaths. The choral group sang the lovely and touching songs from the Old South. Girls openly cried, boys held to a manful welling up.

The black students from the nearby segregated high school marched with us. They brought up the rear. They were not allowed to enter the cemetery. They stood outside, also dressed in white, watching the ceremony from behind the fence.

“Wait a minute!” Wallace Terry said, when I told him this story. “You mean Cheraw forced the black students to honor the Confederate soldiers who’d tried to keep them in slavery? This is crazy!”

“I wouldn’t say ‘forced’ them to attend, Wally,” I said. “Everybody, white and black, got a half-day holiday from school the next day if they took part. That was the point for kids whatever their color, you know how everybody likes to get out of school.”

“I still can’t believe this,” Wally said.

Wally Terry was an African-American journalist for The Washington Post and Time. We were long-time colleagues and friends. We liked to compare notes on the Civil War.

“Well, that was Cheraw when I was growing up,” I said. “The march was discontinued in 1961, two years after I graduated.”

Wally just shook his head, finding it hard to believe. He had not grown up in the South. He asked me to retell my story every time we saw each other. And every time he would look at me and shake his head in disbelief.

But it was true.

|

Janice Terry, wife of Wallace Terry, at the oldest Confederate monument in the South. (Cheraw SC--2006) |

|