By Zalin Grant

This was Monday October 12, 1964. Mary Pinchot Meyer, who’d had a private relationship with President John F. Kennedy for nearly two years until his murder eleven months earlier, was walking on the 4300 block of the old Chesapeake & Ohio canal towpath in Washington, D.C. The towpath area, which bordered the Potomac River, was used as an unofficial recreation park for fishing and jogging. It was a short distance from the Georgetown section of D.C. where Mary lived at 1523 34th Street NW. She was two days shy of turning 44 years old.

On this clear and chilly October day, someone accosted Mary Meyer on the towpath at about 12:20 p.m. and shot her twice within 10 seconds with a .38 caliber pistol. The first shot was directed at her head, one and a half inches to the front of her left ear. The gun was held no more than six inches away because an autopsy revealed that the entrance point of the bullet was encircled by a dark halo of powder burns.

The first bullet traveled from left to right and struck the right side of the skull, then ricocheted back to where it was found in the brain. The second bullet entered over her right shoulder blade and traveled down through the chest cavity, piercing the right lung and the aorta, the heart’s biggest blood vessel. The second shot also came from no more than six inches away, for it too was encircled by a dark halo of powder burns.

According to Willie J. Wade, a D.C. homicide detective I interviewed, the first shot would have produced blowback and caused blood and brain matter to spew on the shooter. Although Wade did not investigate the Meyer murder, he had plenty of experience with similar killings. He told me she would have gone down immediately and died. The second shot was just to make sure. Such a precision-clocked murder sounded to him, he said, like it was carried out by a professional

|

| Police examine the body of Mary Meyer - Oct 12, 1964.. |

The Presumed Killer

Raymond Crump, Jr, age 25, an African American, was taken by police when he was found in the canal towpath area a few minutes after Mary Meyer was killed. A witness said he saw a black man near the body of Ms. Meyer shortly after he heard the two shots. He identified the man he saw as being five-eight and 185 pounds. Crump was five foot five and a half inches tall and weighed 145 pounds.

The D.C. police took Ray Crump into custody and he was charged with the first degree murder of Mary Meyer. As the trial revealed, there was no physical evidence—no blood, no hairs, no fibers—nothing that linked Crump to her murder. No eyewitness claimed to have seen the killing. The gun was never found.

Alfred Hantman, the assistant U.S. Attorney charged with prosecuting the case, told the judge and jury on the first morning of the trial in July 1965:

“This case in all its aspects is a classic textbook case in circumstantial evidence.”

Actually it was a classic textbook case on how to frame a black man for a murder he didn’t commit—something that had already taken place more than a few times in American history.

And the frame-up would have succeeded had it not been for the presence of an African American lawyer by the name of Dovey Roundtree.

Dovey Roundtree, then 51, was one tough lady. This was not obvious when you talked to her. She was polite, soft-spoken, with a mischievous sense of humor, easy to laugh at herself.

Born April 17, 1914 in Charlotte, NC, she had climbed to success with extraordinary grace and determination. After graduating from Spelman College in Atlanta, she served as a captain in the U.S. Army Women Auxiliary Corps (WACs) during World War Two.

At war’s end she got married, moved to Washington, and attended law school at Howard University. Then she went to work with a partner, Julius W. Robertson.

“There were several black women lawyers around the country and several in Washington,” she said. “But none was doing trial work and that’s what I wanted to do.”

In one of her proudest moments, she helped end segregation on Interstate bus travel, winning a case in 1955 involving a black WAC who was forced to give up her seat to a white Marine.

After Mary Meyer’s murder a minister phoned and asked her to meet with Ray Crump’s mother and a delegation from their neighborhood.

“By this time I’d represented many people charged with murder and I was happy to protect their legal rights,” she said. “But there was never any doubt in my mind when a man or woman was actually guilty, and I didn’t let it plague me. I was doing my job as a lawyer.

“At this point, though, I was neutral about whether Crump was guilty or not because I hadn’t seen him.”

When she went to D.C. jail next day, she immediately had misgivings. She found him exceedingly unimpressive. As small as Sammy Davis Jr. and not very intelligent, he was a poor student in school and mumbled when he talked.

Yet he was pleasant enough as a person and not aggressive. He had a construction job and she imagined that he took part of his check home and used the rest to get drunk. She knew the type.

Although she didn’t describe him to me in these terms, I got the impression that Dovey Roundtree thought Ray Crump was not a criminal but simply a low-grade screw-up who was in the wrong place that day.

But his mother was sobbing and asking for her help, and the neighborhood delegation said Ray was a good boy who was married and had five children, and they believed he was being railroaded by the white establishment.

The police were saying that Crump had tried to pull Mary Meyer, who was five-six and 127 pounds, off the canal towpath to rape her. When she struggled with him, he shot her in the head and she grabbed a tree to resist. He pulled her from the tree and dragged her 22 feet away and shot her again when she continued trying to escape.

Dovey had her doubts after seeing him. He didn’t appear to have the proclivities for such an act and didn’t even look capable of dragging a woman who was nearly as big as he was anywhere.

Her doubts were reinforced when she discovered that the prosecutors had skipped the usual preliminary hearing and rushed him to the grand jury and on to trial.

“If I hadn’t been interested in taking his case,” she said, “that got me interested. At the preliminary hearing I would have been able to ask questions, to bring out matters that might have caused the judge stop and consider the circumstances under which he was arrested.”

She was tough in questioning Crump about what he had been doing on the towpath. He told police he had been fishing and had fallen in the water. But he didn’t want to tell her what he had really been doing and she had to pull it out of him.

He had missed the truck that would take him to his morning construction job, he told her finally, and he decided to stop by the home of a girlfriend to see if she was interested in doing something.

The girl had a car and they bought a six-pack of beer and a small bottle of gin and drove to the park, where they had sex. That had happened before, same girl, same place. He drank so much that he fell asleep and the girl took her car and went home and left to him to get back by trolley.

Dovey knew this might make a good alibi if she could find the girl. But she also knew it would squeeze the soul of his poor mother if this came out at trial. When Ray told her he didn’t want to involve the girl she decided not to push it further.

She had dealt with hundreds of black criminals who would walk up to you and put a bullet in your head without blinking, but her gut instinct said he was not one of them. He was telling the truth, within the parameters, of course, of a certain amount of lying.

Mary Meyer

Of all the women alleged in future years to have been involved with Jack Kennedy, Mary Meyer came the closest to matching the social and intellectual credentials of Jacqueline Kennedy—or perhaps exceeding them.

She was beautiful and witty and full of life—an artist with short blonde hair and wonderful lively eyes—who was noted for her abstract paintings.

A niece of Gifford Pinchot, a Pennsylvania governor and the nation’s first conservationist under Teddy Roosevelt, Mary Pinchot attended Vassar, then worked as a journalist, and married Cord Meyer, Jr. A Yale graduate and World War Two Marine, Meyer was an aspiring writer who would become a CIA officer specializing in media propaganda and disinformation.

The Kennedys and Meyers lived near each other in Georgetown when Jack served in the Senate, and they became friends. Jackie often took walks with Mary along the canal towpath.

Mary and Cord were divorced in 1958. But both continued as friends of the Kennedys.

According to an account by Mary’s confidant James Truitt, a Washington Post vice president, Jack asked Mary to stay with him after she attended a White House social function in December 1961. She declined.

As was later learned, JFK was under pressure at this time from the FBI to end his affair with Judith Campbell Exner, a friend of Frank Sinatra who acted as a go-between for the Mafia.

The following month, in January 1962, when apparently JFK broke off with Exner, he phoned Mary and tried again to get her to join him, saying “I’ll send a car for you.”

This time she gave in. She was 42 years old, a beautiful woman who was known to like sex and adventure. A free spirit, many called her. And unlike Judith Exner, she didn’t have any national security issues that might upset J. Edgar Hoover.

Their relationship rose above the quickie philandering that was reportedly of prime interest to JFK. When Jackie was not in Washington, they usually had drinks and dinner alone, but sometimes with one or more of his aides, who would excuse themselves after dinner. They met regularly, often two or three times a week. She began to serve as his hostess at small parties when Jackie was away.

On one occasion she brought six marijuana joints and JFK smoked one of them awkwardly, commenting that it wasn’t the same as cocaine and he would try to get her some coke. But it was unlikely they did drugs again, although there was later press speculation that she had introduced him to LSD, since she knew Timothy Leary and he had given her the drug.

Mary told her confidant, however, that she was under no illusions. She didn’t think he would ever leave Jackie, and she accepted the relationship for what it was.

Did Jackie know? She never indicated she did. But then again that wasn’t Jackie’s style.

30 Years After JFK’s Death

The Mary Meyer case had always fascinated me and in 1993 I decided to take a close look. It seemed enough time had passed that I could conduct a quiet investigation without calling attention to myself or raising the ire of people still concerned with protecting JFK’s image and legacy. I chose November 1993, the 30th anniversary of his death, to start my work.

I got a copy of the trial transcript and studied it closely. I talked to various people involved in the case, and walked the towpath where she was killed. I followed the police investigation and collected documents.

Then on November 3, 1993 I had a long interview with Dovey Roundtree at her Washington office, although I decided not to write my article at that time.

Dovey Roundtree was truly a remarkable human being and I was pleased to see that years later, when she was in her 90’s, she finally began to receive the recognition and praise that she deserved, with a book about her and a television series roughly based on her life, and honored by Michelle Obama. Her Wikipedia entry laid out her career but couldn’t quite touch all the adversities she’d had to overcome to get there.

Dovey thought that there was something in the Meyer case she could never get at. “I felt I was against a big force of the government.” She believed it led to the CIA.

I had no idea about that. But it was clear from my research that the Washington establishment had joined together to oppose the possibility that there might have been another motive for Mary Meyer’s murder besides attempted rape.

Many of these people from government and the media knew each other well. They went to the same Ivy League schools, lived the same lifestyles, and often had dinner parties to exchange gossip. Many of them were enthralled by the idea of Camelot.

Their attitude toward the Meyer murder I found surprising—if not, in some cases, downright suspicious.

Only a day or two after Crump was arrested, the Washington Post had editorialized about the case in a strange and most unprofessional way. As the Post saw it, there was no question about it: Ray Crump was the killer.

Dovey called the Post and asked if they had information about Crump’s guilt that wasn’t available to her. The Post said no, they had nothing that wasn’t generally known to the police.

She heard that Ben Bradlee, the Washington Newsweek Bureau chief, was also trumpeting his belief that Crump was the killer and that it was an open and shut case.

Years later, in a book interview with Brian Lamb, Bradlee said that he never knew JFK and Mary were having an affair until after her murder.

Mary Meyer’s sister, Antoinette (Tony) Pinchot, had married Ben Bradlee, and they lived not far away. Mary used a converted garage edging their property as her studio. Bradlee, along with a Georgetown pharmacist, had gone to the morgue to identify Meyer’s body.

The prosecutor scheduled Bradlee as the first witness, thinking in part, no doubt, that this well-regarded journalist and known friend of JFK would make a good impression on the jury and help build his case.

But Dovey Roundtree wasn’t the least intimidated by the Washington Post or Ben Bradlee, and the way she handled him was the first indication that this wasn’t going to be the open and shut case that the Washington establishment expected.

The following exchange appears in the trial transcript, page 47:

Dovey – Mr. Bradlee, I have just one question.

Bradlee – Yes, ma’am.

Dovey – Do you have any personal, independent knowledge regarding the causes of the death of your sister-in-law? Do you know how she met her death? Do you know who caused it?

Bradlee – Well, I saw a bullet hole in her head.

Dovey – Do you know who caused this to be?

Bradlee - No, I don’t.

Dovey – You have no further information regarding the occurrences leading up to her death?

Bradlee – No, I do not.

Dovey – Thank you, sir. I have no further questions, Your Honor.

There was only one important witness in the case, a black 24-year-old Esso gas station employee named Henry Wiggins. He had been sent from his service station to try to start a stalled auto on Canal Road, across from the towpath, which was concealed from the road by a three-foot high brick fence.

When he got out of his truck, Wiggins said that he heard a woman scream. Then he heard a shot. He ran across the road to stand on the fence so that he could see on the towpath. Within seconds of the first shot he heard another shot.

The Witness Who Saw Too Much

Dovey told me that the black shoes did it for her—and, she thought, for the jury, too. It certainly did it for me when I read the transcript.

There are two things any interviewer, whether media or legal, must be on the alert for: 1) The witness who lies to cover up. 2) The witness who lies to make his information appear to be more than he actually saw.

Wiggins was the second type. He was the source of the first media reports that claimed a witness had seen Mary Meyer struggling with a black man before she was shot. That was later changed to a witness who had seen a black man standing over the body of Mary Meyer after she was shot.

Dovey spent more time with Wiggins than any other witness. She slowly and patiently went to work on him, always politely, taking him through it to dig out every detail he could remember.

It turned out that Wiggins was no closer than 35 to 40 yards from the black man he said he saw. Actually, he said, he only glimpsed him for 30 seconds. But he gave the police a detailed description of what the man was wearing, including that he wore black shoes. It looked like the description was written for him by a policeman after Crump was taken into custody.

It also turned out that the black man was not “standing over Mary Meyer’s body,” as press reports indicated. He was standing behind the body. The head was facing in the other direction where the bullets had entered the body.

It looked as though the black man had just walked up from the rear on the towpath and was staring in surprise at the body. When the black man saw that Wiggins was looking at him, he turned and walked away.

The man was probably Crump who went into a panic when he realized he might be pegged as the killer. But Wiggins’ testimony was filled with so many soft spots that I began to doubt that he even heard the screams of the woman—just the two shots. At the time he said he heard screams he would have been at least 50 yards away and noisy trucks and cars were passing by.

The prosecution was still attempting to build their case that Crump shot Meyer in the head and then she grabbed a tree and held on to it. He pulled her away and dragged her 22 feet and shot her again when she wouldn’t quit trying to escape.

Here is the way it appears in the trial transcript, page 78.

The prosecutor Alfred Hantman is talking to the assistant coroner who pronounced Meyer dead at the scene and who performed the autopsy later that day.

Question – In your opinion, Doctor, could an individual who experienced such a gunshot wound to the head move thereafter a distance of, say, 20 to 22 feet?

Answer – Yes.

If you would like to see the effect of a .38 caliber gunshot to the head like Mary Meyer experienced, click http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nguyen.jpg

Probably the most famous photo of the Vietnam War, taken by Eddie Adams, it shows Vietnamese Gen. Nguyen Loan executing a Viet Cong. The gun he holds is a .38 caliber revolver, the same type that killed Mary. He shoots the VC in the head at almost the same distance and same place as Mary Meyer was shot, though on the opposite side of the head.

The biggest problem the prosecution had was finding the gun. Crump was apprehended within 20 minutes or so after Meyer was killed. The gun was crucial to the case. It didn’t matter whether it belonged to Crump or not, they could always pin it on him, one way or another. The killer didn’t have much time to hide it, so where was it?

The police launched probably the biggest gun hunt in Washington history. They scoured the area. They walked four abreast over every inch of ground where Crump could have walked. They used scuba divers to explore the adjoining canal. When they didn’t find it, they emptied the canal and dug up the muck and mud. They probed the Potomac.

No gun. And no one had ever seen Ray Crump with a gun in his life.

On the day Dovey Roundtree was to present her defense of Crump she wore a pink-and-white striped seersucker dress, with white earrings and white shoes.

She began by calling three witnesses who testified that Ray Crump was known in his neighborhood as a good guy. The only exhibit she used was Ray Crump himself, in all his insignificance, to let the jury take a good look at him.

Then she rested her case.

Alfred Hantman, the prosecutor, was astounded. He asked the judge if they could approach the bench. The judge called them forward.

“Never in my wildest dreams did I think Mrs. Roundtree would rest,” Hantman said.

“You try your case your way and I’ll try it my way,” Dovey said.

Crump was acquitted.

Dovey told him her fee for the trial was one dollar. She insisted that Crump give it to her himself, and she signed a receipt. Then she arranged for him to hide in another state because she thought his life was in danger. She thought her own safety was also at risk. But it wouldn’t be the first time and she wasn’t running.

She believed the real killer was still out there, and the people behind him would stop at nothing.

“I think the word went out,” Dovey said. “Mary Meyer has got to go. When that happens you are just as good as dead. And Crump was the perfect patsy.”

|

Dovey Rountree in 1994. |

|

Camelot Reborn

Two months before Mary was killed, in August 1964, Bobby Kennedy gave a moving tribute at the Democratic Convention in honor of his late brother. It was considered one of the most touching speeches in American history. At the time he was still serving as attorney general under Lyndon Johnson. But the next month he resigned and announced that he was running for the Senate in New York against Republican Kenneth Keating. Keating was popular and everybody thought it would be a close race.

Bobby was being called a carpetbagger, and the slightest misstep could cause him to lose in New York. Although no one could predict what the future held, it was widely assumed that if he won the Senate race it would put him on the path to follow his brother to the White House.

Camelot would be reborn.

Even if it wasn’t known by the general public, Mary’s relationship with JFK was gossip among the elite of the Washington press corps. It was also known that she had become friendly with Bobby after JFK’s death, and since Mary was known to be very generous in her relationships, no one knew how to define “friendly” in this case.

She was keeping a diary, that was known too, and she had confided what she was doing to Ann and James Truitt. Truitt was an experienced and respected journalist, a former bureau chief for both Time and Newsweek. He later said that he kept notes about what Mary told him and his wife.

Backing Into Obstruction Of Justice

It didn't seem to occur to Tony Bradlee and Ann Truitt who were involved in finding and destroying Mary's diary immediately after her death that they might be committing an act of obstruction of justice. They were operating from emotions that were perfectly understandable--blood kin and close friend.

Mary had told Ann Truitt that if she died she would like the diary destroyed, and Ann called Tony Bradlee and told her where Mary kept the journal. People often left orders for their papers to be destroyed on their death and this was carried out—which was fine and legal, when they died of natural causes.

In this case, however, Mary’s diary constituted potential evidence in an on-going murder investigation. Perhaps she had left information that could be used to track down her killer and to stop him from killing other people.

Of course one person certainly knew, and undoubtedly didn’t care, that they were obstructing justice. That was James Angleton, a man so hated and feared by people both in and out of government that William Colby, a former head of CIA, told me in a tape-recorded interview that his firing of Angleton was one of the best things he had done as CIA director.

Angleton was head of CIA counterintelligence and was married to Mary’s closest friend at Vassar. He was a family friend who often invited her two sons for an outing. But apparently Mary didn’t trust him because she told her friends she thought he was tapping her phone, and she suspected someone had entered her house undetected.

Various stories were told about who was involved in finding and destroying the diary. One of the early ones had Ben and Tony Bradlee and Cord Meyer and James Angleton going to Mary’s home together to try to find it. Ann Truitt supposedly phoned Angleton and Tony Bradlee from Tokyo where her husband was based as a journalist and told them where the diary was hidden.

As time went on, the story changed.

|

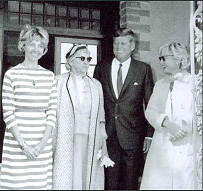

Tony Bradlee (left) and Mary Meyer with their mother and JFK. |

|

Ben Bradlee would probably be remembered as one of America’s finest editors, especially for his work on Watergate. But he came up wobbly in his accounts of what happened to the diary. I had no first-hand knowledge of what he said but relied on quotes provided by others, particularly as found in the Wikipedia entry on Mary Meyer.

According to Bradlee, he and Tony went to Mary’s home the morning after she was killed. The door was locked and they opened it with their key. But when they entered they were surprised to find James Angleton of the CIA, who said he too was looking for the diary. But they were unable to find it at that point.

Again, according to Bradlee, they later came upon Angleton at Mary’s studio near their home trying to pick the padlock on the door. He was still looking for the diary but Tony, acting on info given her by Ann Truitt, found it. They passed it to Angleton, who told them he took it to CIA headquarters and burned it.

But they learned that Angleton had not destroyed it. So Tony got it back from Angleton and burned it in front of Ann Truitt.

One might speculate—although Bradlee didn’t—that Angleton made a copy of the diary and gave the original to Bradlee’s wife for her to destroy, so he wouldn’t later get hit with a rap for obstruction of justice.

According to reports, the diary included the information James Truitt later released and several love letters JFK wrote to Mary.

In early 1963, before the JFK assassination, Philip Graham, the owner and publisher of the Washington Post, mentioned Kennedy’s affair with Mary at a meeting of publishers in Arizona. Graham was already in the throes of the mental illness that led to his suicide in August 1963.

When Graham mentioned the affair, James Truitt quickly intervened and got him off the stage before he said anything more about it. The information obviously had come from Truitt, which probably didn’t sit well with Bradlee and Mary’s sister, Tony.

In any case, Bradlee and Truitt clashed after Mary’s death and their relations became so strained that Bradlee finally forced him out of his job as Post vice president by claiming that he was mentally incompetent. Truitt was given a financial settlement but required to sign an agreement that he would never write “anything derogatory” about the Washington Post.

Truitt moved to Mexico and began trying to get the information from Mary’s diary published. Nobody would touch it. Even the National Enquirer, the scandal tabloid, at first refused to use the material. But when it appeared that Judith Campbell Exner would publish the story about her affair with JFK, the Enquirer went with Truitt’s story. It appeared in early 1976 and was picked up by the mainstream media.

James Truitt committed suicide in November 1981. His wife at the time, not Ann, alleged that his papers and copies of the material from Mary’s diary had been stolen by a CIA officer.

Back Then Journalists Didn’t Tell

I was aware of JFK’s affairs in 1967 long before it became public, though I don’t remember hearing specifically about Mary. I was working as Time magazine’s junior White House correspondent, filling in for Hugh Sidey, usually when he didn’t want to make the drudge trips to LBJ’s Texas ranch.

Hugh Sidey and other top journalists such as Peter Lisagor and Merriman Smith knew about Kennedy’s affairs. Nobody talked about whether JFK was right or wrong. It was just insider stuff, gossip with a chuckle. There were a couple of stories, too, about LBJ’s approach to women which drew laughter.

Back then, nobody in the White House press corps would dream of writing about the infidelities or foibles of a president unless it clearly affected his job. Congressmen were fair game, but not the president.

But Mary Meyer’s death cast a different light on the matter. There was another reason for her death, I believed, that had nothing to do with the black man.

First, there was the way she was killed, execution style. What woman would let someone get six inches from her head without a fight? There were joggers on the path that day and maybe a jogger coming from behind wouldn’t have attracted attention. Or maybe someone she knew pretended to accidentally bump into her on the towpath.

However it happened, I agreed with Dovey Roundtree. It wasn’t Crump.

And what was the reason she was killed? Washington was a political town. It wasn’t difficult to speculate. But I would leave that to others.

At the end of my investigation, I went to the D.C. office where the physical evidence in murder cases was stored. Her murder was a cold case. But some cold cases were solved decades later.

I asked to see Mary’s bloody sweater. Technology was changing. One day the sweater might be tested for DNA under the new methods being developed. Dovey would still be on the case. I knew she wanted to find out who really killed Mary.

The property office told me the sweater, along with everything else concerning the death of Mary Meyer, had mysteriously disappeared.

To tell the truth, I wasn’t much surprised.

|