Vann Nath hears screams of torture every night. He is in a room shackled to an iron bar with 20 other prisoners. He’s at the end of the line. Guards arrive. They slowly begin to unfasten the prisoners until they get to him. They tie his hands behind his back and push him out the door. The other prisoners are herded into a truck. They are driven to the killing fields outside Phnom Penh and beaten to death with shovels and hoes.

"How long have you been painting pictures?" a guard asks.

This might be a trick question, Vann Nath thinks. He answers cautiously: "Since 1965."

"Do you draw beautiful pictures?"

"Not really."

Vann Nath, who is 32, studied art as a youth and opened a small commercial art business in a provincial town. He specialized in drawing colorful movie billboards and did occasional private portraits. He is modest about his talent and clear about being a commercial artist.

He is non-political. He comes from a very poor, fatherless family. He sells noodle soup as a kid to help keep his kin together. After the Khmer Rouge take over the country in 1975, his art business is shuttered and he is ordered to join a peasant commune. He works hard, trying never to draw attention to him or his family.

Vann Nath is a faceless member of the Revolution, which is led by the faceless Angkar—The Organization. He’s nothing more than a worker bee. But on December 29, 1977 he is suddenly arrested and taken to Toul Sleng.

Why?

He has no idea. Like more than a million dead Cambodians, he will never know and will remain bewildered to this day. Cambodia is undergoing what French writer Jean Lacouture later calls “auto-genocide,” something never seen before in history, a people destroying itself for no known reason, except this:

The Organization Orders It.

The guards escort Vann Nath to another building where a man awaits. He sits on a sofa. Thin, late thirties, unsmiling, he’s called Duch. He is chief of Toul Sleng, a former French lycée, which the Khmer Rouge have turned into their torture center in Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital.

|

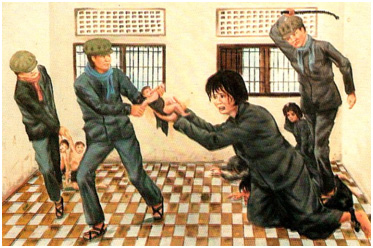

The Khmer Rouge's torture center, called Toul Sleng or S-21, is now a museum that houses many of Vann Nath's paintings, which bear witness to the Cambodian Genocide. |

Duch has read the personal file Vann Nath was ordered to write like everyone who enters Toul Sleng. Duch knows he is an artist. The guards bring a large photograph of Pol Pot. They place it in front of him.

"Do you know why you've been brought here?" Duch asks.

"No," Vann Nath says.

"Listen carefully," Duch says. "I want a clear, correct, and noble reproduction of this photograph. Can you do that?"

"I cannot guarantee it. I haven't painted for nearly three years. But I will do my best."

Vann Nath is assigned to the workroom where a sculptor is making cement busts of Pol Pot. He spends his days painting Pol Pot pictures, which are taken away and distributed.

Fourteen thousand Cambodians will die at Toul Sleng. Only seven will survive. Vann Nath is one of them.

23 Years Later

As Vann Nath and I talk, I feel an odd connection to his experience. He tells me that when he arrived at Toul Sleng most of the people brought in to be tortured and killed were Khmer Rouge from the eastern zone. Pol Pot had turned against them. Unknown to Vann Nath, these were the Khmer Rouge who had captured my future wife Claude, a freelance journalist, and held her for a week in 1970. It was their screams he heard every night.

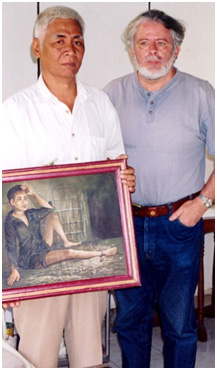

|

With Vann Nath, holding his self-portrait, the only one of his genocide paintings he chose to keep. Phnom Penh—2001. |

I also realized I knew something Vann Nath probably didn’t know about the quirk of fate that had saved him, which I had learned from two high-ranking members of The Organization—Ieng Sary and his wife Thirith. They told me what had happened to Pol Pot in early 1978, not long after Vann Nath was arrested.

Ieng Sary was the Khmer Rouge foreign minister. Thirith was the sister of Pol Pot’s first wife. I was the last journalist to interview them before they were charged seven years later, in 2008, with war crimes. On orders of the government, they were escorted to the Interior Ministry for the meeting with me and my colleague Sos Kem.

When Duch showed him the photo, Vann Nath didn’t realize it was Pol Pot. Like almost all Cambodians, he had never heard of Pol Pot or seen any likeness of him. Duch told him to guess who the man was. Vann Nath guessed Khieu Samphan. He was the public face of the Khmer Rouge and its supposed leader. Duch and the guards burst out laughing.

Pol Pot had always remained in the shadows. This was the mystery I tried to unravel when I interviewed former Khmer Rouge officials on my two trips to Cambodia after the war. How did Pol Pot become leader of the Genocide?

Pol Pot was soft-spoken, soft-faced, smiling. The Khmer Rouge I talked to said he wasn’t as intelligent as Ieng Sary or his wife. Thirith was the first Cambodian woman to graduate from a university. She spoke English and French.

Other high-ranking former Khmer Rouge officials described Pol Pot as a physical coward. They said he never mixed with regular guerrillas, he seemed afraid to get close to them. He refused to reveal his name until after the Khmer Rouge won in 1975, and then continued to maintain a shadowy presence.

|

Ieng Sary, Khmer Rouge foreign minister, and wife Thirith. They were later charged with war crimes. Photo by Sos Kem--2001. |

|

|

|

Thirith—ex-KR told me—enjoyed seeing people buried alive.

(Photo-ZG) |

|

I asked Ieng Sary about the Pol Pot mystery. He seemed amazed himself. He said his former brother-in-law had gathered power shrewdly, almost without contention. Then he enforced it with his one-legged military commander, Ta Mok, who was not political but very efficient at killing anyone who opposed “Brother Number One.”

"But why did he start killing so many people," I asked.

"It was a matter of strategy," Thirith said.

"No! No!" her husband quickly interjected, touching her thigh to stop her from speaking further. "It wasn't strategy. It was because Pol Pot didn't want to ask the help of any foreigners, he wanted Cambodians to be self-sufficient. Pol Pot didn't start out with the idea of killing so many. He started by going after those he considered traitors. Then it didn't stop."

But I knew Thirith had blurted out the truth. It was in fact a strategy—to create a new society by killing off the old. Total ignorance and complete docility was to be the starting point, an empty slate upon which they intended to write their lunatic ideas about abolishing money and establishing an agrarian Utopia. Ieng Sary and his wife were complicit in the Genocide though they tried to deny it. They had the blood of untold thousands on their hands.

|

A Band of Murderous Brothers. Pol Pot far right. Ieng Sary 3rd left. Khieu Samphan 2nd left. Nuon Chea not pictured. Pol Pot executed the rest—1973. |

"At the end he began to think he could do no wrong," Ieng Sary said. "He acted like a king."

They described to me the Mao-like busts Pol Pot ordered made of himself, not long after Vann Nath was arrested, in early 1978, one year before the Vietnamese invaded and overthrew the Khmer Rouge regime. They said that Pol Pot’s Chinese adviser, a super Rasputin sent by Mao himself, had convinced him that he should establish a personality cult like the Chinese leader.

That was why Duch started looking for a sculptor and a painter. The sculptor he found easily. And then a commercial artist was brought to Toul Sleng. Vann Nath did not know it but he had been saved by Pol Pot’s Mao-inspired megalomania.

After the war, Vann Nath was shown an execution list dated February 16, 1978, signed by Duch. His name was on the list but underlined in red with the notation “Keep.” Everybody else had been killed that day.

When he read the list, Vann Nath said, “I felt as weak as though my body had no bones.”

After the Vietnamese drove out the Khmer Rouge in 1979, Vann Nath was united with his wife but learned that their two young sons had died of starvation. Toul Sleng was turned into a museum the next year, and he returned to Phnom Penh to bear witness to the horror he had seen.

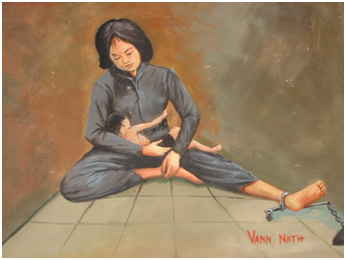

|

The deepest horror was the way Khmer Rouge ripped babies away from mothers and crushed their skulls.

(Vann Nath—Genocide Museum) |

As my interview with Ieng Sary and Thirith came to a close, I was ready to ask what I had planned as my last question. I wanted to give them a chance to see Vann Nath’s work.

“Have you ever been to the Genocide Museum at S-21?”

"No," they answered together.

"Would you like for me to arrange a private visit? I think I can set it up for you. I'll be your escort."

They laughed nervously. They knew I had good enough contacts with the Cambodia government to arrange that. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have been sitting for this interview, which was not voluntary on their part.

"No, we don't want to go,” they said. “We just want all Cambodians to love each other."

EPILOGUE 2009

In the next few years after he was freed, Vann Nath confronted several of the Khmer Rouge that he suspected had been involved in his arrest. But his most dramatic moment came when he saw Huy, former chief of security at Toul Sleng.

“It took me 15 minutes to compose myself,” Vann Nath recalled in his memoirs. “What could I say to the person I had been more afraid of than a tiger? Now suddenly he was standing right in front of me.”

Vann Nath walked up to Huy and stared him in the eye. He said, “You are Brother Huy aren’t you?” Huy turned and spoke to him in a gentle manner, pretending not to recognize him. Vann Nath told him who he was. As Huy began to lie, he challenged him aggressively on every point. Slowly, Vann Nath began to see what a weak and insignificant man Huy really was, the very personification of the so-called banality of evil.

He turned the conversation to his paintings in the museum, which Huy said he had seen. “Are they exaggerated?” Vann Nath asked.

“No, they are not exaggerated,” Huy said. “There were scenes more brutal than that.”

“Did you see the picture of the prison guards pulling a baby away from his mother? What did you and your men do with the babies?

“Uh, we took them out to kill them.”

Vann Nath shouted in shock: “You killed those babies? Oh my God!”

He had always thought they had spared the children. This overwhelmed even his worst nightmares about the Genocide. With nothing further to say, Vann Nath walked away, unsteady on his feet, and never saw Huy again.

Those kinds of confrontations took place all over Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge killers claimed they had been victims themselves. They said they would have been killed if they disobeyed The Organization’s orders. In fact, more than a dozen guards at Toul Sleng were executed.

Duch told Steve Heder, a Cambodia specialist, that he realized near the end that the logic of the revolution meant that he himself would eventually be executed, so he began to ignore his duties and pass the time reading novels in his office.

This was one of the reasons why I believed ten years ago—and still believe today—that none of the remaining members of The Organization would be punished by a war crimes tribunal. The part of Cambodia’s population that suffered through the Genocide had not been able to come to grips with it. They were still stunned by what happened.

How does one come to grips with insanity? They asked me what I thought the Genocide meant, looking for an answer from an outsider. I had no answer.

Many of them wanted revenge and wished to see the remaining members of The Organization punished. But few of them wanted to take it further. Too many people were implicated—in one way or another, the whole country, including Hun Sen, present leader of Cambodia. Some of them were ready to accept that the killers had also been victims.

Duch was an easy target. He was not a high-level member of The Organization but a clog in the killing machine. Since his crimes were well documented, he was likely to spend the rest of his life in prison. But he was not nearly as important to understanding what happened as Ieng Sary and Nuon Chea and Kieu Samphan.

Youk Chang and the Documentation Center of Cambodia unquestionably deserved, in my opinion, a Nobel Prize for their courage and tireless work over many years to bring members of The Organization to justice. But I feared that was unlikely to happen.

Pol Pot never expressed any regret or remorse. He and his killer-in-chief Ta Mok died in their sleep. Probably, I thought, so would Ieng Sary and Thirith and Nuon Chea and Kieu Samphan. It followed the logic of an insane revolution.

At the end of our breakfast interview, Vann Nath told me he never wanted to do another painting about the Genocide. He was sick of thinking about violence and brutality and death. He said he would show me the last two paintings he had kept from his genocide period. We went to his roof-top patio where he worked. He brought out his self-portrait which he said he would never sell. The other was his portrait of Mother and Child of the Genocide.

It is a heart-wrenching portrait. But it doesn’t belong on my office wall. It belongs where it will be seen by many people to remind us that someplace in the world, at any hour, The Organization still exists.

|

Vann Nath's "Mother and Child of the Genocide." One of the last paintings from his genocide period. (ca. 1980). |

Notes:

1. Vann Nath’s memoir: A CAMBODIAN PRISON PORTRAIT: One Year in the Khmer Rouge’s S-21 (White Lotus Press - Bangkok:1998)

2. Google “vann nath paintings” for further information.

3. For sales information about Vann Nath’s “Mother and Child of the Genocide” click on Collectibles in the top menu or http://pythiapress.com/vann-nath/painting.htm |