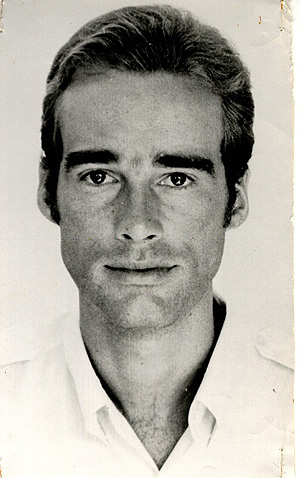

Sean and Errol Flynn had only one thing in common. Both were uncommonly handsome. At six-two, blond, hazel eyes, Sean was considered by many to be le plus beau. Like his father he attracted women. Unlike his father he didn’t chase skirts. Neither was he a boozer or a brawler.

In fact, Sean was reserved, especially around women, and always polite. He never fully escaped the middle-class values instilled in him by his mother—Lili Damita, a former French actress, whom Sean loved but sometimes found a bit too much of a mother-hen. Since his battling parents divorced when he was born in 1941, he barely knew his father until his teenage years. Then his most memorable son/dad experience came when Errol stole his recent LA girlfriend who was 14 years old.

Sean’s personality seemed to disappoint many people. They wanted him to be more like his dad. It seemed to go better with the story of the war photographer who was ready to take it over the top. After all, he was also a sort of movie star like Errol Flynn and had played “Son of Captain Blood.” Some people were even ready to embellish stories about Sean to make him sound more like they wanted him to be.

This was what Sean had fought against his whole life. He didn’t want to be known as a copy of Errol Flynn. And he chose the only way he knew to prove that he wasn’t—he went to war. His dad was pretend-brave in war movies with fake explosions. Sean was brave in a real war with explosions that blew off heads and legs. Vietnam was Flynn taking on Flynn.

Sean and I played the war game. Photographers in the field clicked photos of each other in case the other guy got killed and they could make some money off it. Macabre as it might sound to outsiders, we all took it as an in-joke. A photographer snapped your picture when you weren’t looking. You turned and stared him in the eyes. Both of you smiled.

Sean and I had our version. We were the same age, born within six weeks of each other. He took photos of me. I reciprocated—with a tape recorder. He never liked talking about himself. But we decided to have a long tape-recorded conversation on February 21, 1969 at his apartment in Saigon.

As we both understood, I would never use it—unless, of course, something happened to him. And I didn’t. But here it is 40 years later.

|

Sean Flynn arrived in Saigon at age 25. |

|

When I was fifteen I got sent to a prep school in New Jersey. It depressed me. I didn't like the Brooks Brothers atmosphere. So much of this is easier now because I can relate to it in a more sophisticated vocabulary. I'm trying to think back to what I felt then.

The only thing I knew then was that I didn't want to go to Princeton. My prep school, Lawrenceville, was a feeder for Princeton. I didn't want to go to an Ivy League school. Get a business degree, work on Wall Street, marry a socially acceptable girl. It just wasn’t there.

The summer I got out of prep school actor George Hamilton phoned me in Palm Beach. I'd known George since we were kids messing around on the beach. He had a role in a movie they were making at Fort Lauderdale, called "Where the Boys Are." He introduced me to the producer, Joe Pasternak.

Pasternak says, "Hey, I know your old man, kid. I think we can do something for you in this film."

So I did a walk-on, that's what it amounted to, I threw a football. As a result of the publicity the producer who'd done the original version of "Captain Blood," the film that made my father famous in 1935, gave me a call and said, "Look, how would like to do a real film? I've got this great idea—‘Son of Captain Blood.’"

I realized if I did this I would be doing "Son of Zorro" and all the rest. But the financial side of it was attractive. My mother was never lavish with her money. I got an education and clothes and stuff like that. But I didn't get a tremendous allowance like some of my friends. Not that I necessarily wanted the money. But the movie sounded like a good way of becoming independent.

It was what I was waiting for because I didn't really want to go to college. To placate the guys at home, I agreed to go to school one year before I did the film. I went to Duke for a semester.

Duke was a beautiful place. But my grades weren't very good. So it was sort of a mutual thing when I withdrew. And it was weird, because at Duke I suddenly found myself president of my freshman class. This was very strange for me. I was getting out of my depth. I don't enjoy being the center of attention or having to lead.

So I dropped out and went to California, to get ready for the film. I did a little fencing with stunt men, took voice lessons. This went on for six months. I enjoyed the work but I soon wanted to get out of California. Perhaps I'm a conservative at heart, but I had to get out. Out of that smog and away from those freeways.

Everybody I met was extremely cynical and knew everything. To them, screwing a girl had nothing to do with love. Even liking a girl was a kind of therapy. Life just didn't have much meaning. And I was trying to get away. My mother is a very generous person with her attention. I felt smothered, I guess, by her generosity.

What can I say? I was a bit like a hick coming to the big city. I met quite a few young actors. The scene gyrated between Palm Springs and Hollywood to Malibu. I fooled around, but I wasn't interested in it. I'm not the gregarious type. I don't make friends easily.

At nineteen, I felt very ill at ease and out of place.

•

The director of “Son of Captain Blood” was a Spaniard who spoke no English, little French, and Flynn couldn’t talk to him. But he was patient with his young American actor. Sean liked him. The movie went well, it made money, and even Time gave it a good review.

None of the other of his ten movies fared as well, except for “Stop Train 349,” with Jose Ferrer, which went to the Berlin Film Festival. Sean was paid $30,000 per film. When he had saved enough to live okay in his family’s Paris apartment, he started turning down offers for further film deals.

Many years later my wife and I happened to see one of his movies on French television. We were both surprised. He showed signs of real talent that could have evolved if he’d stuck with it.

•

The war was going on and I was curious. I’d bought a Leica in Spain but I hadn't done any work as a photographer. I spoke to the people at Paris-Match and asked if they would be interested in any pictures I might take in Vietnam. I thought perhaps I could do better than one of their staff people—little did I know!—because I was an American.

They said, "Yeah, let's do it."

But it wasn't for the reasons I gave. They were interested in Sean Flynn, son of Errol Flynn, at war. I caught a taxi at the Saigon airport and gave the address I'd got from the Paris-Match guy. The driver takes a look at it and says, "You sure you want to go there?" I said yes.

So he takes me there. I've got a couple of suitcases, an attaché case, a camera, and a tennis racket. I get out the cab and turn around to see this gaping hole of a wrecked hotel. This was early 1966 and the Viet Cong had blown it up a few weeks earlier.

The American press office in Saigon didn't want to accredit me. They said the letter I had from Paris-Match wasn't sufficient. I got a girl in France to send me some Paris-Match letterhead stationery, and I wrote my own letter, which was accepted.

I heard there was going to be a big operation in the Central Highlands called “Masher-White Wing.” I caught a flight to the press center the First Cavalry Division had set up in tents. I didn't know fuck-all about what to do.

Somebody said, "If you want to go where the fighting is you just hang around the medevacs and they're going in to pick up the wounded."

I found the medical evacuation helicopters and saw people like Eddie Adams of AP and Johnny Apple of the New York Times. We waited around about an hour or so and the pilots started to crank up and we all piled in.

Christ, we landed in one of the hottest actions of the war! South Vietnamese troops were coming up with armored personnel carriers on one side. The North Vietnamese were on the other side. We were in the middle. And they were shooting it out.

All the photos I took were bad—underexposed. But I was glad to be in Vietnam. Maybe it was proving something, I don't know. A lot gets lost in perspective, a lot of old personal battles. After you get the shit scared out of you a few times, it's easy to look back and forget what was actually going on in your mind.

You see, the movies were obviously something I didn't like. I won't say I wasn't interested. But I always felt—I don't mind fighting my father. But I realized I was fighting him on his own turf. It came down to that. I was in a false situation.

But I felt at home in Vietnam. I found out right away that I liked the—it’s hard to say you like war. But I liked the excitement. I felt my strength would be my ability to function under fire, in this case to perform as a photographer.

•

I met Flynn a few days after he arrived in Saigon. He came to the Time bureau in the Continental Hotel. Here was this handsome guy who looked more like a soldier than most officers. He was wearing green army fatigues with a combat harness. Dangling from the harness were four M-26 grenades.

Time reporter Jim Wilde, whose name was an understatement, practically started jumping up and down when he saw Flynn.

“What do you think you’re doing, doctor?” Wilde demanded, pointing to his grenades.

The safety lever of the grenades was not taped. Even in combat soldiers kept their grenades taped. If not, in case of a serious bump or accident, the safety pin might be jerked out and the grenade would explode, killing everybody around.

Flynn looked stunned. He didn’t have a clue as to why Wilde was upset and yelling at him. As he later told me, when he arrived in Vietnam he didn’t know the difference between a major and a colonel. A compliant doctor had kept him out of the draft with an imaginary knee problem. He learned fast, though, by spending most of his time in the field.

•

I went with the Green Berets to establish a new camp. We walked all day. We were supposed to reach water but couldn't find any, so we turned back. The VC had watched us go out. While we were gone they set up an ambush. And when we came back down the path it hit the fan.

The VC had a light machine gun and a couple of AKs sitting right in the middle of the trail. I was the eighth guy back. Couple of guys in front were killed with the first burst, others wounded. I hit the dirt. I could practically feel the muzzle flash of the machine gun.

We fought our way out. But the men were pretty testy after that. In the next several days, we caught a sniper who had shot into a church filled with refugees. He had wounded a little girl. |