"Zalin, I like the war letters you write," my Paris friend Henry

is saying. "But they are décalé, don't really fit in

this section. Why don't you create a different page for them on your website?"

"Yes, you're right," I say. "I thought I would be writing just one and

it wouldn't matter in the context. So now there are three. I'll leave them

here for the moment and then maybe move them later."

Note to the reader: As Henry says, this war stuff doesn't really

fit with the other material which is solely about France, and this letter

might not be of interest to you, so my advice is to skip it. My style, my

language, and my attitude change when I return to the former war zone, and

this might be disconcerting to readers who prefer the French Letters. I feel

like I am putting on my old war correspondent's clothes. (If only I could

fit into them!) This is a report I prepared for circulation on my recent Cambodia

trip, addressed to Ann Mills Griffiths, Director of the National League of

POW/MIA Families, in Washington, D.C..

This is the view from the hotel where Sos Kem and I

and the Pentagon team stayed during the investigation into the missing

journalists in Kratie, Cambodia, which looks like an old French colonial

outpost. |

Ann is an old friend and colleague on this issue, but in no way responsible

for my report.

In fact, I financed the project entirely, except for an unsolicited

personal contribution by Murray Gart, the former chief of the Time-Life

News Service, who originally asked me to undertake the investigation

in 1970.

Several guys familiar with my work have warned me that I have revealed the

area where the newsmen are probably buried, and are worried that with the

increased tourism in the Kratie area, some adventuresome souls might attempt

their own excavations. I would strongly recommend against it. There are still

plenty of unrepentant bad guys from the war who now know exactly what we are

doing and who probably don't like it. For this reason I have included an excerpt

from my coming book that doesn't appear in the report I sent Ann Griffiths.

It describes my encounter with two Canadian schoolteachers who were riding

bikes from Stung Treng to Phnom Penh. The book is to be called The War

and I: A 30-Year Search for Sean Flynn, Dana Stone, and Other Missing Newsmen.

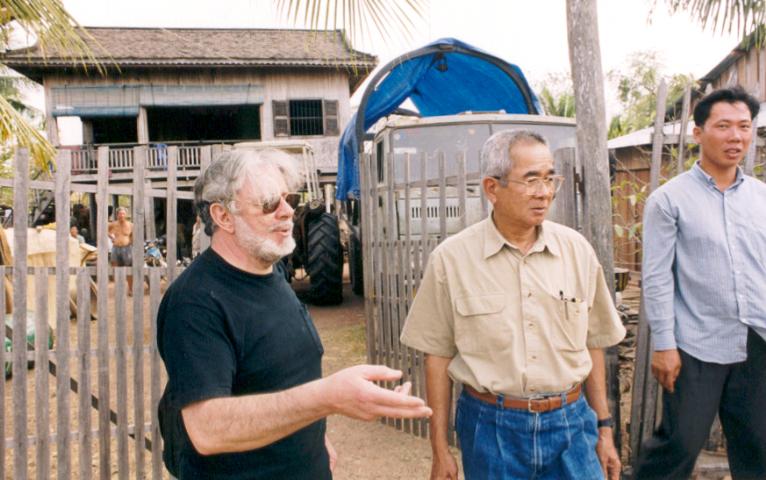

Sos Kem and I spent our days searching for sources we

could turn over to the Pentagon team, so they could make their own investigation

into the missing journalists. We found them. |

|

| Sos Kem works his magic. In private, he has a warts-and-all

take on his fellow native Cambodians. But he treats everybody with courtesy and respect, no matter what their station in

life. Which is why he is so good as an interviewer. Note the teapot in the middle. He refused to drink it

after I told him I thought that was why we were getting sick--drinking unpurified water in tea. He's not

that courteous! |

CAMBODIA REPORT-02

This is an account of my trip to Cambodia from February 8 through February

26, 2002, as part of an ongoing investigation into the capture of approximately

17 international journalists--including three American citizens--in 1970.

As you know, I have been involved in investigating the disappearance of the

newsmen since April 1970, when I was asked to return to S.E. Asia by Time

Magazine and CBS. Sean Flynn, on assignment for Time, and Dana Stone, on assignment

for CBS, were among the missing. In 1973 I made a second trip to Cambodia

at the request of a committee of journalists headed by Walter Cronkite of

CBS; and I returned again in January-February 2001 to do further work, along

with my Cambodian-American colleague, Sos Kem.

OVERVIEW

From 1970, I believed that a group of the newsmen, approximately 10 or 12,

including Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, were moved from their place of capture

on Route One north toward the Mekong River town of Kratie. My belief was based

not only on my independent investigation but also on reports from the Defense

Intelligence Agency, the State Department, and the U.S. 525th Military Intelligence

Group in Vietnam. I was further persuaded in 1973, when I picked up an eyewitness

report from a Cambodian detained in a Khmer Rouge camp outside Kratie who

said he had seen ten newsmen in mid-1972. This information was supported by

a 525th MI report based on a North Vietnamese officer who said he had seen

two of six newsmen being held in a house in Kratie in 1971. The eyewitness

was given and passed a lie-detector test.

During the period 1970-1975, when I was most active in investigating the

newsmen's capture, I received the cooperation of the Pentagon and the State

Department. I met numerous times with officials who were responsible for the

POW/MIA issue, and we freely exchanged information. Walter Cronkite placed

into the public record all the information we as journalists had collected

in 1976, when he testified before a U.S. congressional subcommittee.

After 1975 I noted a lessening of official interest in the question. I did

not find this surprising, since the Pol Pot regime had closed off Cambodia.

What I did find surprising, though, was the Defense Intelligence Agency's

unilateral decision to declare that the Khmer Rouge had executed Sean Flynn

and Dana Stone in 1971, without offering the least credible evidence. I was

almost certain that this was not true, and that the DIA was confusing reports

about the execution of Humphrey and McKay, two defectors to the Khmer Rouge,

with Flynn and Stone. However, this remained the DIA's official position for

15 years or more, until investigators working under the newly formed Joint

Task Force-Full Accounting established with reasonable certainty that a mistake

had indeed been made by confusing Humphrey and McKay with Flynn and Stone.

With such a prevailing attitude and a lack of official interest in the missing

newsmen, I realized that I would have my work cut out for me if I were to

persuade the Pentagon to reopen the investigation, after my trip to Cambodia

in January-February 2001, when I was able to confirm the physical information

on the Khmer Rouge camp provided by my 1973 source and also to establish the

location of a possible gravesite.

Nevertheless, with the help of concerned individuals, both within and outside

the government, we were able to get the Pentagon investigation reopened. It

was scheduled for October 2001. The October investigation was canceled and

rescheduled for February 2002.

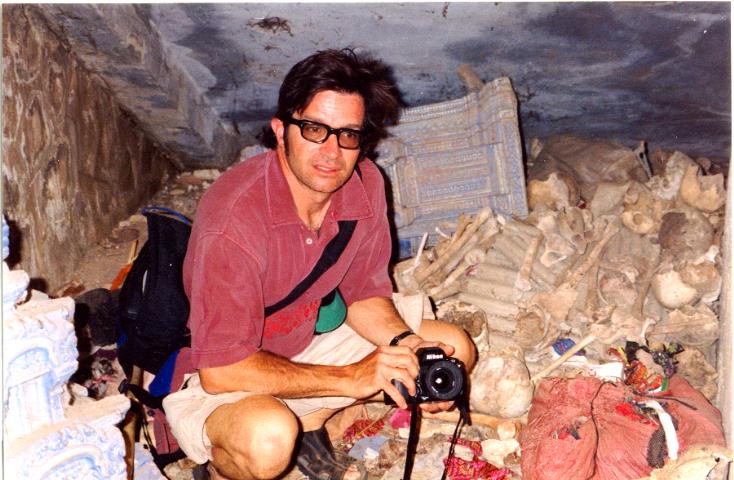

This is Richard Linnett, freelance journalist. If you've

got a better candidate for the quintessential New Yorker, let me know.

This guy has everything: the look, the accent, the attitude, the humor,

the intelligence, and the je ne sais quoi that I really don't want to

know. Here he is sitting in a Buddhist wat next to our hotel, in a storeroom

that contains the bones of victims of the Cambodian genocide. He asked

me to pose with a skull, said it would make a wonderful photo. What I

told him should not have been overheard by anyone but a sailor. Despite

a rocky start, we wound up having a lot of fun together. |

RESULTS

February 9, 2002 - Saturday - We have breakfast at the Intercontinental Hotel

with General Pol Saroeun, Gen. Saphin, Sieng Lapress of the Foreign Ministry,

and Col. Soyath of the Cambodian MIA office. I have asked Sos Kem to set up

this breakfast as a sort of courtesy call on the Cambodian officials before

we get started. Gen. Saroeun tells Col. Soyath to phone the police commissioner

in Kratie and order him to meet us and act as our guide and facilitator.

February 11-Monday - Sos Kem and I arrive by water taxi in Kratie.

We immediately begin to try to develop leads that might confirm and expand

the information we collected the year before.

February 12-Tuesday- The Kratie police commissioner picks us up after

breakfast. We return to the village Kapo, where we spent time last year. The

villagers greet us as though it had been only yesterday. It is polite to drink

the tea they offer. But I tell Sos Kem I have figured out why we got sick

last year: the Cambodians don't bring their tea to a boil. I pretend to drink

my cup but he doesn't touch his.

February 13-Wednesday-Richard Linnett, a journalist who arrived in Kratie

with us, tells me that Marine Col. Neil Fox, the JTF deputy commander, and

Air Force LTC Mike Dembroski, the Cambodia detachment commander, are at our

hotel and would like to meet me. They apparently are checking out the hotel

for the arrival of the JTF team. We go for soft drinks at a nearby restaurant.

Fox explains that the JTF team will run an investigation and if a determination

is made that the matter of the missing newsmen should be pursued, perhaps

a test dig will be made. He emphasizes that this is a test dig and not an

excavation. He says, "Zalin, we are all on the same team. We are all working

together." After our drink, they chopper back to Phnom Penh.

February 14-Thursday - Sos Kem and I begin to develop important information

from several sources. One is a Cambodian restaurant owner who served as a

liaison with the Vietnamese during the war and who can lead us to other sources.

INSERT FROM BOOK

Richard meets two Canadian schoolteachers, attractive, especially the blonde,

both thirty. They teach English in Taiwan. He invites them for a drink at

the Riverview. I stop by as I return from sending an e-mail at an NGO that

has the only Internet connection in Kratie. The two women have flown to Cambodia

with their bicycles, gone north above Kratie by boat to Strung Treng, and

now have begun to pedal south toward Phnom Penh. It sounds like a great and

unusual adventure, and they are obviously having fun.

"Look," I say, "I don't want to spoil your trip, but I'd like to give you

a little advice. I know that women like privacy when they go pi-pi. But don't

step off the road to do this. Especially don't do it when no farmers are around

and nobody is working the fields."

I remember what Adrian told me. He is a retired Dutch army colonel who runs

a program to collect and destroy weapons in Cambodia. They have collected

50 thousand so far. "Only three million to go," Adrian says wryly.

"I tell them," Adrian says, talking about the guys who work with him. "'Piss

on the road.' But they don't listen. They step off into the bushes. And bang!

They've just lost a leg or their life."

"Cambodia is one of the most heavily mined countries in the world," I tell

the two schoolteachers. "The UN-sponsored Belgian Army de-mining team says

that the country won't be free of mines for 80 years, at the rate they're

going. Remember, nobody wakes up in the morning and says, 'Well, I think I'll

go step on a landmine today.' But look around you."

Instead, they look at me--like I'm crazy. Who is this guy?

"Oh, don't mind Zalin," Richard says. "He's an old dude, a little conservative

now."

"Yes, I agree," I say. "But I spent few years in the Vietnam War, and I'm

still standing. A lot of that was luck. But something else was involved, too."

We drop the subject and begin to talk about traveling. I tell them about

my yearlong drive overland in a VW camper, first from Singapore through Malaysia

and Thailand to Laos, then back to Singapore, ship to Sri Lanka, and then

India, Nepal, Kashmir, and a push on to Paris. Susan and I were thrown into

a horrific cholera quarantine camp for two weeks (despite our valid shots),

after we crossed the Afghan border into Iran, one of the worst experiences

of my life and especially for Susan, who had to face the leering Iranian secret

police.

The teachers begin to look at me in a new light, and question me about the

trip. Travelers develop a trust for each other. If you want to know what to

do, where to stay, how to get by the cheapest way, you talk to another traveler

who has been there. I can see them thinking about what I said earlier. Some

of their effervescence has disappeared.

Maybe I have spoiled their bike trip. Maybe I have saved their lives. Maybe

both. Who knows?

Later Sos Kem says: "Those girls are really courageous, aren't they?"

"No," I say. "They are really adventuresome. My definition of courage is

understanding fully the risks--and then taking them, if you believe it necessary

or worth the possible consequences. They don't understand the risks, it's

all abstract to them. If you see somebody get their legs and arms blown off,

it changes your whole attitude, sort of concentrates your mind."

ENDS BOOK INSERT

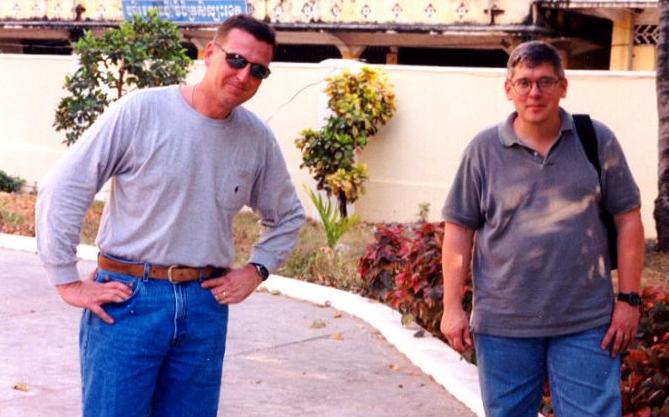

| Col. Neil Fox, (white shirt above), deputy commander

of the JTF, and Major David Combs (to Fox's right), beginning a "test

dig" at a reported gravesite of the missing journalists. Fox was later

quoted in a news story as saying they had made an "extensive" dig and

no further action was warranted. On the right you can see what they did.

A couple of feet to the left of the trench could have been the burial

site of 50 bodies for all they knew. |

|

February 15-Friday - The advance party for the JTF team arrives by

Russian-made transport helicopter, loaded with supplies and equipment. They

are surprised to find Richard Linnett waiting for them, snapping photos. One

of the team members says, jokingly, "Are you the infamous journalist we've

been hearing about, the pushy guy who is pushing for this operation?" Linnett

tells them that he is a journalist but probably not the "infamous" journalist

they are referring to. The advance party brings a couple of truckloads of

supplies--including their microwave oven, two-burner stove, bottled water,

lockers filled with food, equipment for the operation--and sets up in the

hallway of the Sante Pheap (Peace) Hotel, which is on the main street overlooking

the Mekong.

February 16-Saturday - The main party arrives by helicopter around

11 a.m. The team commander and the investigation team ask to meet with me.

We set up in a circle outside the hotel on the red folding chairs they have

brought. The investigation team says they are going "to start from scratch"

on this investigation. They would like to ask me about my background and would

like for me to tell them how I can prove the newsmen were moved to the Kratie

area.

I notice that one of them holds a notebook containing files I have already

provided the JTF and also a copy of an article that appears on my website

which goes into detail about my background. Still, I try to cooperate fully,

explaining that I did my military service as an Army Intelligence Officer,

that I was, for a time before the buildup in 1965, head of army intelligence

operations in I Corps; that after my discharge I became a journalist in Vietnam

for Time and later The New Republic, and spent a total of five years in the

war.

I am surprised that they say they are going "to start from scratch" on this

investigation. How can they start from scratch after 32 years have elapsed?

I try to point out in a non-contentious way that my analysis of where the

journalists were held is not simply based on the information I have collected,

but also on the information that their own organization has collected--that

in fact I have with me an interview the DIA Stony Beach team did in 1998 with

a Khmer Rouge eyewitness to the newsmen's capture, which follows in near perfect

detail the eyewitness reports I wrote in 1970. They want to know where they

can find my reports. I tell them that Walter Cronkite made these reports part

of the public record in 1976--which comes as news to them.

I offer to turn over all the sources Sos Kem and I developed in Kratie last

year and the ones we have developed so far this week. I emphasize that I believe

this is their investigation, not mine, and I am phasing myself out. In fact,

Sos Kem is leaving the next day, Sunday, for Phnom Penh. I also offer to show

them the possible gravesite area and introduce them to the sources Saturday

afternoon, which I do.

February 17-Sunday - The Stony Beach investigators begin to follow-up

and re-interview the leads Sos Kem and I have developed.

Some people, when they hear "intelligence," or "CIA," or "DIA" mentioned,

get the impression that esoteric techniques are being put into play, something

that ordinary people cannot understand or do. But in this case, the Stony

Beach team is doing only what tens of thousands of civilian women and men

do every day in jobs where normal interviewing techniques are used, whether

it involves job interviews, college admission interviews, bank or credit interviews,

or interviews conducted by journalists. The point of this interview is to

elicit information quickly by using a non-aggressive approach to establish

rapport and to put the interview subject at ease. In this case, the only special

technique needed is a cultural sensitivity to Asians in general and to Cambodians

in particular. That is why I have depended upon the light-handed approach

used by Sos Kem and have tried to keep myself in the background.

Now I am hearing from our sources that they find the Stony Beach team intimidating.

Four of the members speak Khmer to varying degrees. According to my sources,

none of them speaks it well enough to be operating without a native Cambodian

speaker. These are farm folk out here and it is even difficult sometimes for

Sos Kem to understand them. I realize I've got to have a translator. Sos Kem

left this morning. Richard Linnett spots a cherubic-faced nineteen year-old

kid who speaks English fairly well and, as we learn later, is serving as a

part-time pimp for some of the JTF team. His name is Poun, and I think he'll

do okay.

One of our most interesting sources of last year was a rice farmer named

Ban Poev. What he said, and what I wrote, is that he saw around ten bodies

of persons he believes were kept at the Khmer Rouge camp, about 300 meters

away, where I believe the newsmen were held. Ban Poev said to Sos Kem and

me that he was told by two Khmer Rouge that these were "intellectuals, important

people from Phnom Penh." This was, of course, a key point, and Sos Kem went

over it a number of times with Ban Poev, and we came away convinced this is

what he had heard and seen.

Now I hear that Ban Poev, under Stony Beach grilling, has backed off from

his "intellectuals, important people from Phnom Penh" statement and denied

that he ever said it. I'm not surprised. I'm more surprised that he hasn't

denied that he even talked to us last year, considering the techniques the

DIA team is using. Another source, Ry, a low-level security cadre, whom Sos

Kem and I believe has lied to us and knows much more than he is telling, is

completely avoiding Stony Beach team.

Interestingly enough, the Stony Beach team tells me they also believe Ban

Poev is truthfully relating what he saw, and say they like him.

I hear that Col. Fox has examined the area from the air and concluded that

the depressions Ban Poev told us was the possible gravesite are B-52 craters

turned into buffalo wallows. As Fox later says, this doesn't mean someone

isn't buried there, since it would actually be less work to bury someone in

a hole already dug.

Tom Munroe (left) and Joe Fraley of the U.S. Defense Intelligence

Agency.

We had a "full and frank exchange of views," as the diplomats say,

one evening at the Riverview Restaurant in Kratie, on the modus operandi

of the DIA--just male posturing, really. |

|

February 18-Monday - I am working in my room with a computer I have

rented from "Save the Children," an NGO. I have the largest room in the hotel

where the JTF is staying. When I arrived, I was put into a smaller room but

Sos Kem spotted this room and I told the hotel manager that I wanted it. It

was $5 more, $20 as opposed to $15. The manager, a tall, young sensitive-looking

Cambodian, says, "I am sorry, Mr. Grant. The pilot of the JTF has reserved

this room. I say, "Fuck the pilot. He won't be here until the end of the week

and I'm ready to rent it now." The manager says, "I see your point, Mr. Grant."

I hear a knock on the door around eight a.m. I wrap a sarong around me and

answer. It is Col. Fox. He peers into my room, clearly surprised by its size.

"A change of plans," he says. We are going to do a test dig on your site.

Do you want to come along?" "I certainly do," I say. "But I didn't arrange

for a car today, so I don't have transportation." "Maybe you can come with

us," Fox says.

In a few minutes Col. Fox returns. He says, "We're leaving now. You can go

with us." I have to close down the computer. I leave quickly, without hat

or bottle of water. The van awaiting us is empty. It is only Fox and I. When

we are underway, he gives me another little homily on how they are doing the

best they can, how we are all on the same team.

I like Neil Fox. Not "like" in the real terms of like, because I don't really

know him. Nor do I think he really "likes" me. But Richard Linnett and I agree

that he is acting like a professional, in trying to handle two potential loose

cannons; he is doing his best. He doesn't look like a Chesty Puller Marine.

He is of medium height, not fat, glasses, low-keyed, more like an understanding

schoolteacher who cheerfully expects a certain number of his students to flunk,

perhaps us among them.

I tell Neil Fox that I am dismayed by the Stony Beach attitude that they

are going "to start over from scratch." I say that these reports are already

on record. Why don't they have them? I say, "You guys are intimidating the

Cambodians. You pull up in your rented vans and jump out like a SWAT team.

You all look military with your short haircuts and look-alike clothes." Fox

doesn't agree--or disagree. He says something to the effect that he sees my

point. He is not going to be drawn into an argument.

I learn that Richard Linnett the journalist has been taken by helicopter

to another site where a search is underway for military remains. Linnett is

in the hands of LTC Dembroski, while Fox is handling me. Good thinking: Kill

two birds with one stone--rather, one day.

The test dig involves two sites, chosen on the basis of what Ban Poev has

said. Sergeant First Class Greg Parmele, the assistant team leader, explains

the reasoning behind their choice. I barely listen. I know this is the best

I am going to get from them--take it or leave it. I'll take it.

One team of Cambodians starts to make a trench about a half-meter wide, one-meter

deep, for perhaps six meters. It's hard going. Everybody works. Col. Fox joins

in the sifting of soil and rocks. Major David Combs, the team leader, a muscular

guy with an oval patch of hair on the top of his shaved head, takes part in

the digging. I "like" Combs too, a quiet guy, former enlisted man and ranger.

The digging is so hard that they order a second team of diggers from the Cambodian

farmer and his wife that Sos Kem and I have developed as sources.

I came without a hat and without water. I feel like I am developing a heat

stroke. I plead that I must talk to the Cambodian farmer's wife about a source

who is supposed to show up later. The farmer leads Sgt Chuuk and me to his

house. A JTF van pulls up. I ask Chuuk to tell him to take me to my hotel,

where I'll find a car and return.

I can hardly make it to the shower. I have lunch at the Riverview Restaurant

and then ask them to fill a thermos bucket with iced Cokes and water bottles.

I return to the site. The team is about to leave in a van, en route by helicopter

to a military remains site. Nothing has been found. Which means this: Nothing

is there--or maybe something is there, six inches away on either side where

the trench has been made. I pass the Cokes to the team, and thank them for

their effort. Only Col. Fox refuses.

I call Col. Fox aside and say, "I know you are not interested in excavating

the termite hill site which has been identified by a source. Do you mind if

I do it?" I seem to have caught Fox by surprise. He says, "No, go ahead."

It is not that I think I will find something. It is just that I won't feel

satisfied if I leave Cambodia without taking every shot that I can.

I stop by and talk to the farmer's wife, Narine. I arrange for her to have

a team do the excavation on Wednesday. When we first met and Sos Kem was talking

to her husband and she was taking a submissive position, I noticed her body

language, and I told Sos that we should talk to her, not to her husband, who

I thought was nice but not a very bright light. Sos did so and sent her his

ten-dollar radio by Richard when he left. She immediately wrote him a thank-you

note, and our relationship was cemented. Narine has ten years of education

and was trained by the U.N. to be an elections observer, now trains other

women to do the same. She is a Cambodian feminist.

In the evening I invite the Cambodian officers assigned as liaison to the

JTF team for dinner at the Riverview. It is a long dinner, lots of beer, very

cheerful, only Richard Linnett and I and them. They understand what I am doing,

and one of the officers takes me aside at the end of the dinner. "We don't

care if you dig up the whole province," he says. "But don't cause trouble

between us and the JTF. We will have to work with them after you leave." "Agreed,"

I say.

So we decide to do our own excavation. Richard wants

to have t-shirts made and call it the Z Task Force. But Maj. Combs humorously

tells him that is not correct military terminology, it must be Task Force

Z. When I tell them Richard is my personal minesweeper, walking backward

in front of me in the fields, taking photos, they get a laugh from that. |

|

This is Narine, 55, my chief of staff for the excavation. She

hired the diggers, prepared the food, and kept a gimlet-eye on the workers,

including her husband.

When her husband once sat in "my" chair at their house,

she said something that caused him to shoot out of it like a rocket. |

Poun, 19, my translator, is sitting directly in front

of me. He's still in high school and says he is lousy in math, science,

and physics but good in language and literature. I said, "You sound like

a natural journalist to me." So that is what he says he wants to be. I've

asked Richard to stay in touch with him, and maybe we can help him. |

February 19-Tuesday - In the afternoon I drive out to see Narine,

to make sure the operation is on for tomorrow morning. I had asked her

to get six diggers. Now I ask for ten. I figure the whole thing will

cost me a little over a hundred dollars. Let's splurge.

Richard Linnett arrives on his rented red Honda motorbike, the kind

Sean Flynn and Dana Stone were riding when they disappeared. Linnett

has turned out to be an asset to what I am trying to do. He gets along

well with the Cambodians. I tell him that Narine has agreed to be my

chief of staff. He congratulates her. She giggles like a teenager.

The JTF van pulls up. I can see Col. Fox sighing. They are on our heels

again, waiting for Ry, our source who is avoiding them. I tell Fox the

Cambodian liaison officers don't care if we dig up the province, so

long as we don't cause trouble with the Americans. I say, "I told them

it is straight with you." He says, "Yes, it is straight."

In the evening, Linnett and I are sitting with some enlisted men from the

recovery team. We mention what we are doing, and they soon leave, finished

with their meal. Not ten minutes later the Stony Beach team, plus Major Combs

and his assistant Greg, arrive and take seats at our table. This doesn't seem

like an accident. They are looking for us--or rather, for me.

I say I am pleased that they have accepted me on this mission, and I know

it must not be easy for them to have a journalist and outsider intruding in

their business.

Tom Munroe, a warrant officer who works as an analyst for Dickie Hites, says,

"Oh we like journalists more than lawyers about this much." He holds his thumb

and index together with a space of about one-tenth of an inch. The others

laugh. To my front are Greg Parmele, Tom Munroe, and Joe Fraley. To my right

are Major Combs and the youngest member of the Stony Beach team.

I have my doubts about some lawyers and even some journalists--but I don't

go about insulting them to their face, and Munroe has clearly intended this

as an insult. He is particularly outspoken in the conversation that ensues.

It becomes an argument. I don't tell them what I really think--that they are

intimidating the Cambodian sources, that they don't speak Khmer well enough

to operate without a native speaker.

I formulate my argument in more general terms. "How long are you guys going

to take to wrap up Cambodia?" I ask. "At the rate you are moving, I think

you'll be here for at least 20 more years. If you really threw yourself into

this job, you could close it out very soon, because the Cambodians are giving

you more help than anybody in S.E. Asia." I make it very clear that I think

they are not pursuing their job with appropriate vigor and concentrated focus,

that they are spending too much time in Hawaii and not enough in Cambodia.

The work here calls for a lot of shoe leather and perseverance, not just devoting

two or three days to running down leads on one case and then making a hop

skip and a jump to another case--and then speeding back to the beaches of

Hawaii.

"Why is the Cambodia detachment based in Bangkok, not here?" I ask. "Why

is Sgt Chuuk, a Khmer speaker, sitting around Bangkok?"

"It is a logistics hub for the whole S.E. Asia operation," they say.

"Fuck logistics," I say. "You don't need a lieutenant colonel

and Chuuk doing that. You can get two sergeants to handle that."

We are getting into areas that neither they nor I really know about--budget

considerations, Pentagon allocations. Voices are raised. It is getting out

of hand. We both begin to back off.

They tell me, "As far as we are concerned, your mission has been a success,

because you have opened sources to us that has led us to all kind of things."

I'm rather shocked by this, although I know it to be true. I am surprised

that they would admit it. Still, I'm not ready to back down despite the compliment.

I tell them that the American public is fed up with this attitude of "Continue

to Investigate," which is the last line of every DIA report and is simply

a catchall cover-your-ass. Get on with it and reach some conclusions. Not

every case is going to be resolved, but take every case to the end and then

ask Ann Mills Griffiths to call the family members in and you explain what

you have done.

Major Combs, the team leader, has not said anything during this argument.

Suddenly he gets up and says, "Let me get out of the line of fire." He is

partially blocking my vision of Joe Fraley, who is opposing me vociferously.

Combs takes a seat to my left. Fraley tells me what a hardship it has been

for him and his family to take the Phnom Penh assignment. I have had dinner

with him and his wife Lisa, I know better. Bullshit, I say, you took the assignment,

now do the job, get up here by water taxi like Sos Kem and I have done, costs

ten bucks and six hours of your time.

They admit that I have made certain valid points. And I admit that I don't

know all the problems they are facing in terms of budget constraints and Pentagon

matters. What I don't say, but they know I am leaving unspoken, is that I

still don't think they are doing an adequate job. The overall organization

of the JTF looks fine. This is a case of the tail wagging the dog. Everything

depends upon the Stony Beach guys, and they just aren't up to it. I've always

had great respect for enlisted men. But where are the officers involved in

the intelligence collection effort? The JTF has got a bunch of former sergeants

running their entire show.

For the first time, Major Combs speaks up: "Off the record, I can tell you

that changes are going to be made. The new command doesn't necessarily think

like the old command."

This can go on all night. I break it off. Tom Munroe comes to me as I am

leaving and apologizes for some of the things he has said. We shake hands.

I apologize for raising my voice and using an expletive that begins with F.

Major Combs also shakes my hand and bids me good night. This is a polite formality.

I realize that when the Stony Beach team arrived in Kratie they didn't like

me. But it was nothing personal on their part. Now it is.

February 20-Wednesday - The excavation comes off as scheduled. Among the

ten diggers are Ban Poev and the elusive Ry, neither of whom I had requested.

They all have a good time. I have prepared water bottles, sliced apples, water

melon, and other fruit for a 20-minute break after the first two hours of

digging-a little better than the JTF team treated them, working them straight

through the noonday heat. We find something that Ban Poev and others claim

is highly decomposed bone matter, the type they find when they dig up the

graves of their ancestors. I don't know. I show it to the JTF anthropologist

when I return to the hotel. He believes it is organic material and what they

thought as bone fragments is wood. He says he will put it into their system

for final analysis. He seems a decent and earnest worker, and I have no expertise

myself on this subject and thus no grounds to argue. I thank him for his time.

I will run my own DNA tests in Europe.

February 21-Thursday - The JTF team is leaving, in two waves of helicopter

transport. I sit in the hotel lobby talking to Major Combs. He tells me that

the Stony Beach team has developed two separate eyewitness sources that place

at least seven Caucasians in Kratie City either in 1973 or 1975. "Really?"

I say. I am not surprised. Although I turned over all my sources to the Stony

Beach team, they have somehow forgot to tell me about this. I wonder what

will happen to the information. "Continue to Investigate"? Two of my sources,

which the Stony Beach team also interviewed, confirmed that "foreigners" were

held in the Toul Sleng-like lycee in Kratie, about two miles from the original

camp where I believe the newsmen were held. So foreigners were held in Kratie,

probably after the end of the Vietnam War. This is the weight of the evidence.

I believe they were newsmen, but they could be military. What is the Pentagon

going to do?

I tell Major Combs about the report I did on the probable death of Newsweek

reporter Alexander Shimkin in Quang Tri Province, Vietnam, in 1972. I think

I had his gravesite fairly well pinpointed. Tom Munroe and Joe Fraley walk

into the hotel. They are just minutes away from being lifted out by helicopter.

Combs tells them quietly to make a photocopy of my report. Munroe looks at

Fraley and asks him if he wants to do it. Fraley says no. So they both go

to photocopy it. They return after a few minutes and give me the original.

Their demeanor is not one of happy campers.

February 22-Friday - I leave Kratie for Phnom Penh by water taxi, six hours

down the Mekong, ten bucks, nice way to get a suntan. I was developing good

source information up till the last minute. I wonder if it will ever reach

the Stony Beach team.

February 26-Tuesday - I arrive back in Paris.

February 27-Wednesday - I write Ann Mills Griffiths and tell her

I will soon send her a report on my trip to Cambodia. She replies quickly,

as follows:

Zalin: Glad you're back safely and I really look forward to your detailed

account since you write them in an unvarnished way that is very informative.

Thanks again, and I hope you're not too disappointed at not having been able

to recover the remains of your colleagues. I don't think that this endeavor

is the end of it, however. Take care. Ann

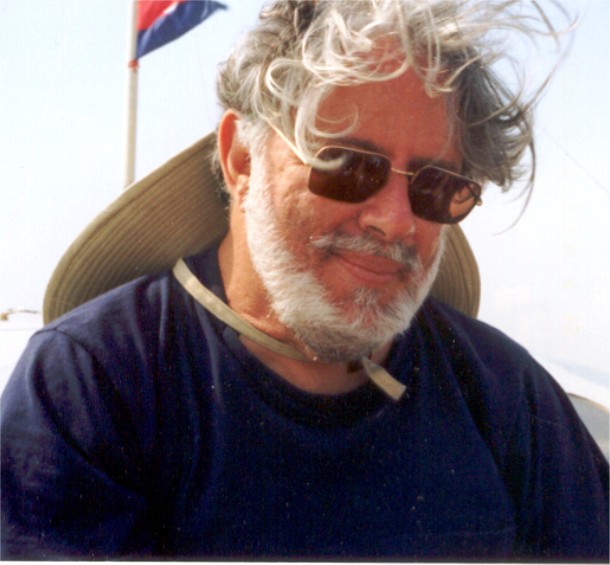

On the Mekong River, February 22, 2002. Leaving Kratie and heading

to Phnom Penh and then Paris. Will I go back? I don't want to. But I never

say never. (Photo by Richard Linnett) |

|