I can't remember the first time I did it. What comes to mind is the wonderful

sensuousness I felt, it was everything I thought it would be. Actually it was

more. I didn't realize I would like it so much and would develop a powerful

craving that will surely follow me to the grave.

Oh, I'm not talking about that first time! Of course I remember the first time

I did that. It happened on the front seat of my secondhand black Plymouth,

Wednesday evening, June 19, 19--well, just a few weeks ago, it seems. No, I'm

talking about the first time I ate a French oyster. Maybe it happened on my

first trip to France--yes, now I remember. That would put it exactly ten years

after I had the other first time. So I can celebrate a double anniversary this

year--my 35th and 45th.

|

Thierry Sorlut, 35, (left) is teaching me to be an oysterman.

His great-grandfather started the family business.

|

If it's true that oysters are an aphrodisiac, as many people think, I

would be in detention right now, because during the winter I eat dozens

upon dozens.

I get them from my friend, Thierry Sorlut, who drives five hours from

the Atlantic coast every weekend and sets up his stand in a nearby town,

bringing a truckload of oysters just plucked from the water the day before.

But this is not a story of an aphrodisiac, it's about a delicious act

of cannibalism, for the oyster is the only animal eaten alive by human

animals around the world.

And this is where a guy like Thierry Sorlut comes in. The French are strict

about insuring that their oysters are safe. But if you buy at a big supermarket,

especially during the hectic market period of Christmas/New Year's, when 40

percent of the year's oysters are sold, you may wind up with little animals

that are about to exhaust their life cycle. If stored properly, an oyster can

live around 17 days after being removed from the water. But who wants that?

That's why I like to know my oysterman. This is something I picked up from

my wife Claude. Like every good French cook, she makes it a point of getting

to know her butcher and fish vender. If you put the relationship on a friendly

personal basis, you'll have more confidence in what you are eating and often

wind up with something better than a faceless customer gets. She certainly does.

Thierry Sorlut tossing a net to his dad before hopping aboard

their boat to begin a day's hard work as an oysterman. |

Thierry's village is on the island of Oléron, just off the Atlantic

coast. Oléron is the number one oyster producer in France. Number two

is the Bay of Arcachon, not far from Bordeaux, which happens to be where we

vacation every summer. There was an old formula that you could only eat oysters

during months which contain the letter "r," effectively putting May,

June, July and August off limits. But that has changed and now they can be eaten

year round. Cultivators have learned to manipulate the reproduction cycle. Some

even practice sterilization by genetic modification, although my summer oysterwoman

tells me that the technique is forbidden on the Bay of Arcachon, where producers

make much of their money selling freshly hatched oysters to other cultivators

around the country.

The oyster has sex only with itself, it's hermaphroditic. (Not only are you

eating a live animal but also a hermaphrodite!) Actually, an oyster is essentially

a water filtration machine. It has no brain or propulsion capability. It can

sift about two gallons of water (8 liters) an hour looking for nutrients such

as plankton. And here is the key point to oyster cultivation. It can also absorb

pollutants, and toxic metals like mercury, lead, and cadmium are especially

dangerous. But professional cultivators like Thierry Sorlut are acutely aware

of the danger and they are constantly testing the water to make sure it is pollutant-free.

I had a fantasy about becoming an oyster cultivator, until Thierry started

telling me what is involved. It's hard physical labor, dawn to dusk work. For

this reason, a lot of the younger members of oyster-raising families are fleeing

to the cities and finding jobs that involve trolling a computer.

The first step begins with the newborn oyster, which is just a speck. The Romans,

who began cultivating oysters two thousand years ago, noted that newborn oysters

attach themselves to some object in order to grow. So a support system for their

growth is the main element of the oysterman's parc, which in this case

means oyster bed or enclosure. Depending on the region, the support system is

made of iron rods, tiles, or plastic tubes. It doesn't much matter. Oysters

will attach themselves to an old rusty bike tossed into the sea.

Oysters grow for 18 months on a support system and often

stick together. Now they are separated and prepared for the second step.

That's Thierry at a younger age helping his mom. |

After the oysters are taken from the support system and sorted by size, they

are placed once again on tables in the water for another few months or a year.

An oyster is ready for the market between two and three years of age. The next

to last step is called affinage, which means "refining" the

oysters in an enclosed basin, which gives them a good taste. The final step

is the purification process, which takes place in an artificial basin. The oysters

must stay in this strictly controlled clean water for a minimum of 24 hours.

That is when Thierry plucks them from the water and brings them to our market.

The oysters are sorted by size and age and given a number. I like the number

1 or 2's, which are on the fat side.

Oyster cultivation involves a lot of heavy lifting. This is Thierry's father. |

Now that Thierry has brought us fresh, tasty oysters, some of the best

in France, all we've got to do is flip them open in two seconds and enjoy

them, right?

Unfortunately, it is not that easy.

Opening oysters is a craft that demands practice. At my first New Year's

Eve celebration after we moved from Spain to France, I was charged with

preparing over 200 oysters for the party.

Claude and her friend Annie kept darting into the kitchen to tell me

what a lousy job I was doing. Finally, after hearing my job report six

times, I said, "It's obvious that you two know more about this than

I do, so please be my guests."

I poured myself a glass of white wine and walked out of the kitchen,

leaving them with 18 dozen oysters to open. That was the last criticism

I heard about my skills with an oyster knife.

Actually, I was doing a lousy job. When I wasn't stabbing myself,

I was leaving enough broken shell mixed with the oyster to provide the

partygoer with a calcium supplement enough for a month.

I'm opening oysters at our vacation place on the Bay of Arcachon.

This is a trick my friend Pierre Muller taught me. He has got a little

plastic box, looks like a soap container, and you put the oyster inside,

pull the top down, then insert the knife in the side where the valve muscle

is located, and twist upward. You don't risk stabbing yourself. I eat

oysters in July and August too--neither one an "r" month.

|

|

|

| Oysters are divided into two parts--the top, which is flat, and the

bottom, which is curved. The two parts are held together by a muscle. Insert

the blade into the side where the muscle is located and cut it. Here is the

way the professionals do it. Hold the oyster with the flat part up and the widest

end pointing forward. That puts you into the position to cut the muscle by inserting

the blade, moving it back and forth, and twisting up to remove the top. Don't

try this without a glove or other protection. I'm pretty good at it now, but

every time I get a little over confident and forego the protection, I wind up

punching a hole in my hand. |

My favorite way to eat oysters is by opening them one by one, leaning over

the kitchen sink, at 7:30 in the morning. I leave the oysters covered overnight

on the outside sill of the kitchen window and they are nice and cool. This of

course is not an ideal hour for drinking white wine with the oysters, and once

when Claude saw me clearing my palate afterward with a gulp of Diet Pepsi, she

practically screamed: "You barbarian!" "Chaque américain

son goût," I replied.

If you are on a trip to France and not very familiar with oysters, you might

not want to go to the trouble of preparing them yourself. I suggest that you

find a good Paris bistro that has a seafood stand outside. These stands are

manned by écaillers, professionals who prepare seafood platters

for the bistro, shivering in the cold. You can fully trust them.

And don't forget, when you eat your first oyster in France, write down the

date. Then, unlike me, you will always be able to remember this first time,

too.

The Foie Gras Imperative

Oysters are one of two special treats most often found on French tables at

Christmas and New Year celebrations. But not all French like oysters. Practically

every one of them, though, likes the other holiday treat--foie gras. This

simply means "fat liver," duck or goose, cut into slices and eaten

with bread or toast. And of course accompanied by wine. Foie gras used to have

an aura of elitism about it, but production costs have dropped and it has become

popular with all segments of French society.

|

| Veronique in the boutique next to her home where she sells freshly-made

foie gras that contains no preservatives. |

As it turns out, one of the first and major foie gras producers in our

region lives only a twenty-minutes' walk from our house. Veronique Affray.

I've known her and her husband for years. In fact, we have a deal with

them whereby they give us a year's worth of foie gras and other things

in exchange for cutting and baling our hay for their cows. It's a convenient

way of keeping the fields around our place clean.Now this sounds like it would be the easiest interview in the world, doesn't

it? I know Veronique. And she lives right down the road.

It took me six months to do it. First, I was trying to finish a book and didn't

want to break my rhythm, to stop writing about war to write about foie gras.

Then after I finished the book, I ran into conflicts with Claude's schedule.

She went to Spain. Then to Portugal. Then back to Spain.

Finally, I said, "I'll talk to Veronique by myself. I don't need you.

I want to get this Letter done."

"You don't know anything about foie gras," Claude said. "You'll

need me."

"What do you mean? I've been eating foie gras for years. I can tell the

difference between the good and the mediocre."

"I don't mean that," she said. "You don't know the different

kinds and the precise steps of its production. You'll need me at least the first

time you talk to her."

"Then let's do it," I said. "This is taking far too long."

"Okay," she said. "Tomorrow morning before I leave for Paris."

Actually, the delay had a more subtle reason than just a conflict in schedules.

Although we didn't admit it, we were both reluctant to talk to Veronique. I

said that we've known her for years, which is true in a superficial sense but

not really in the sense of "knowing" someone. She and her husband

are always busy, a blur of action and hard work, and our exchanges had been

on the level of Bonjour, ça va?" "Oui, ça va. Et vous?" In

fact, like other people around here, we referred to them as Monsieur and Madame Canard.

Farmers often work by instinct and are passionate but not very articulate

in describing what they do. French farmers particularly speak in proverbs about

when to plant and when to harvest, based on the phases of the moon, the weather,

and other semi-superstitious things that generally prove accurate. We were under

the impression that Veronique and her husband had just started a foie gras business

as a subsidiary to their farm of cattle and sheep, and were sort of amateurs

who learned to do it.

How wrong we were!

Veronique is preparing for the key step in the production of foie gras--the force-feeding of the ducks. |

Veronique's husband has nothing to do with the foie gras business. This

has been her deal from the beginning. And she's not an amateur who made

good but a trained professional.

Besides that, she is quite articulate and gives a vivid and detailed

description of how foie gras is produced.

It gets even better. Veronique has shown extraordinary courage and initiative

in establishing her business.

Veronique grew up in a nearby city. Her family had a metalwork business. As

a young girl, she wanted to be a career military officer or a farmer. Why? She

can't explain it. It was always one of the two. She decided on raising goats

and making cheese. She was taking a course but didn't much like it. A fellow

student was learning foie gras production, and Veronique got interested. She

signed up and took 200 hours of formal instruction, then spent a year as an

intern learning by experience. It was there that she met her future husband.

She was 21 when she finished her course. She heard about a farm on a small

river outside our village that was for sale. She got a loan from Crédit

Agricole France and bought the farm. She moved in and immediately started her

foie gras business.

This was high audacity for several reasons. A young girl, an outsider to boot,

taking over a farm by herself? And starting a foie gras business? It was unheard

of, this is the center of France. Foie gras is mostly produced in the southwest,

the Périgord, and the northeast, in Alsace. She was the first producer

in our region.

She soon won over the skeptics with her hard work and professionalism. People

started showing up at her farm, asking to buy from her directly. She also began

selling through shops, and eventually opened a boutique in a city with several

other women, specializing in farm products that are fresh and contain no preservatives.

Veronique's husband, Aimé, in the saddle of his tractor,

where he spends much of his days. He's cutting our hay in August. |

Veronique orders 400 ducks a year. They used to cost $4 each, but because

artificial insemination techniques have been developed the cost has dropped

to $2.50, lowering the price of foie gras and making it more accessible

to the general public.

The one-day old ducklings come by mail. Veronique keeps them in a temperature-controlled

shelter for a month and a half. Then they are allowed outside but kept

separate from the older ducks.

At three and a half months the gavage--stuffing--of the duck to

create a fat liver begins. It lasts 18 days. Veronique uses moist corn.

She starts little by little, forcing the corn into the duck's stomach,

until she reaches the stage where she is feeding each one twice a day,

more than two pounds (a kilo) of corn. She hopes to produce a liver that

weighs at least a pound, or half kilo.

I was surprised by the amount of corn used in the daily stuffing, also by the

size of the liver. A pound? Gee, that's a big liver coming from a small duck.

The gavage of course is the controversial part of foie gras production.

That some people criticize the process doesn't seem to bother Veronique, this

is her business. She points out that a sick or unhealthy duck, or one not properly

cared for, won't produce the size and quality of the desired product no matter

how much it is stuffed.

I carried a vague misconception about foie gras production. I thought it was

done just for the liver. But while that is the most profitable part of the business,

the entire duck is processed and sold, including the magret, or breast,

which, in another act that might not find favor with some French purists, I

like to barbecue.

Claude and I never try to proselytize our tastes. People who oppose foie gras

or who are vegetarians are always welcome at our home. We always have plenty

of fresh vegetables and fruits, so there is never any problem whipping up an

alternative meal for anyone. But--hmmm--how we enjoy foie gras If you love it

too, drink a toast to us during the holidays.

Veronique force feeds the ducks corn twice a day, reaching

two pounds a day over 18 days. This enlarges the liver. It is then cooked,

seasoned, and vacuum packed for sale. |

The Foie Gras Dissenter

Deborah Palmer is an art history professor at the American University of Paris

and a graduate of the Ecole du Louvre. She is one of our closest friends, an

American who has spent most of her life in Europe. Deborah is an animal rights

advocate, but she is against people who try to force their beliefs on others.

She believes that society is slowly evolving in the way it regards animals and

the kinds of food that should be eaten.

"If you live in the Arctic of course you need to wear fur," Deborah

says. "But why kill minks for a coat in Paris or New York?"

When she was a kid, Deborah had a goose named Amélie. She became uncomfortable

eating Amélie's compatriots and finally stopped. Then she subscribed

to an animal magazine, and read an article about foie gras which was a shocker.

It said the ducks lived in a permanent state of nausea. (I didn't observe any

reluctance of the ducks to undergo the gavage.)

"I don't run around telling people they shouldn't eat foie gras,"

Deborah says. "My mom cries about the process but still eats it. I quit."

When Deborah visits, I tell Claude, "Let her eat radish, with buttered

bread, the way the French like it. I'll take care of the foie gras"

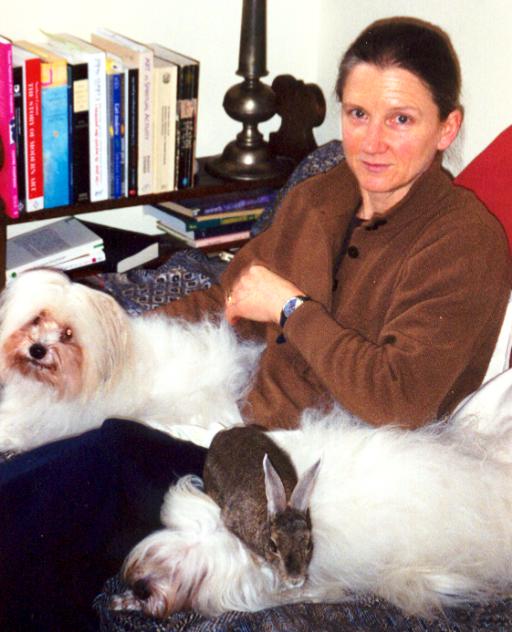

|

Deborah Palmer and her brood at her Paris apartment.

Prudence is a wild rabbit that Deborah found in a field and turned

into a pet. She is writing a book about the experience.

I've never heard of a wild rabbit being tamed and Deborah doesn't

use that word to describe her, but Prudence, now 14, is remarkably housebroken

and loves to play with the dogs.

I had a few pointed words for Prudence after she ate my telephone

wires, leaving me without a phone for a month. But I gave her a carrot

and we made up. |

Good Neighbors

Robert Frost is always quoted as saying "good fences make good neighbors,"

which is a distortion of the actual poem. I like Hesiod's quote much better:

"A bad neighbor is a misfortune, as much as a good one is a great blessing."

The holiday season reminds me that we have always had "great blessings."

From Spain to France, our neighbors have been some of the nicest people in the

world. The French stir a certain ambivalence in some American minds--and vice

versa in French minds. I have to admit, an American bureaucrat can sometimes

seem like the soul of compassion compared to his French equivalent. And the

attitude of Paris shopkeepers that the customer should say hello first and act

honored to give up his money is still a bit irritating.

But, really, we have always been surrounded by neighbors of warmth and generosity

and integrity. And I'd like to honor a couple of them during this season.

Monsieur Lucien Pierre and his wife Suzanne are our closest

neighbors in every way. They have been married 53 years, and were childhood

sweethearts.We could walk out of our front

door on five minutes notice and not return for a month, and we wouldn't

have the slightest worry about our house or our animals. They would take

care of everything. The trust between us is absolute.

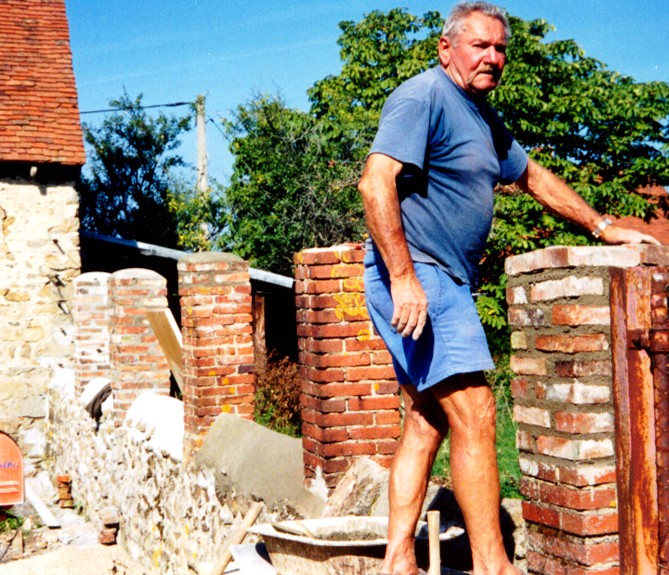

Here Monsieur Pierre is rebuilding our barnyard fence,

which he volunteered to do, as he does so many things.. |

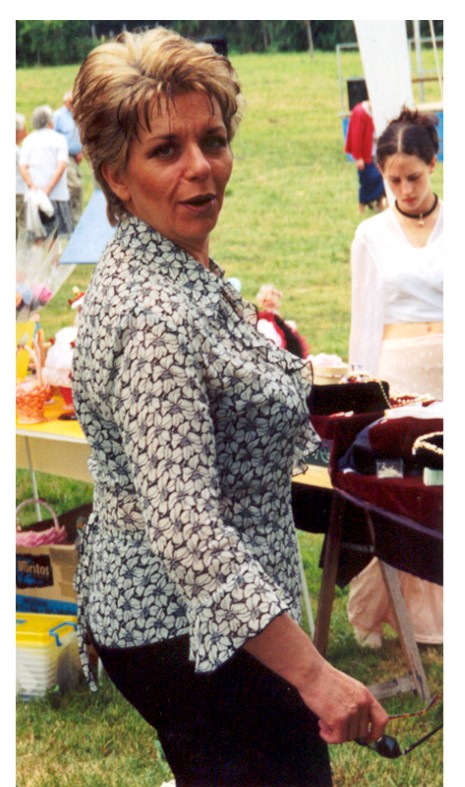

Chantal and her husband Gilles and son Maxime live around

the corner from us. I was overjoyed to learn

she is a coiffeuse domestique--a hair stylist who

makes house calls. No more waiting an hour or

two in the

village barber shop, listening to guys

talk about prostate problems, hunting,

and who

drinks too much. Chantal is the only haircutter

I've ever known

who actually does what you ask

her to do. Her good-neighbor price is not bad

either--$14 to do my hair and beard. |

|

This was taken at our home on New Year's Day. Between Christmas and

today I had

eaten 10 dozen oysters. We are going to start with foie gras for lunch.

|

|