A weird wedding? Is that what I am in for? I'm wondering.

French weddings traditionally are staid affairs. The wedding vows have been

set by the government since Napoleonic times and no deviations are brooked.

There are no skydiving marriages, no marriages at a nudist colony, or in the

snow. You get hitched at town hall, in the mayor's office, by the mayor himself

or his deputy--or you don't get hitched at all. That's the law. Afterward, you

can have a church wedding if you wish, and the state doesn't care, but you aren't

married unless you do the mayor first.

Yet I've heard that the young French are finding ways to lighten it up a bit.

They can't change the vows, or the march to the mayor's office, but they can

change the ambience--sort of like tarting up Marianne, the symbol of France--to

make the occasion a little more fun. This is what I've come to check out. As

I drive to the village where the wedding is to be held, a car pulls out in front

of me. The rear of the car looks a llittle strange. I flag down the driver and

ask him to let me take a photo, which he laughingly obliges.

The bridegroom is a pompier, a fireman, and that's what the dummy

on the back of the car represents. The pompiers are the most highly

respected group in France, even more so than firemen in America, if that's

possible. In case of an emergency you call the pompiers first,

dial 18, and they'll be right there. Even little girls dream of growing

up to be a pompier.

The bride is a hair stylist. The two of them live outside Paris, but

both are from the village of Saint Sauvier--300 inhabitants--not far from

where we live. There is something else about this wedding--well, not really

weird, but a little unusual. Her mother is the secretary to the mayor's

office. His mother is the deputy mayor.

She is going to marry them.

|

|

| The bridegroom's mother, Yolande, who is the deputy mayor of Saint

Sauvier--and Marianne, the symbol of France. Both of them wear the sash of the

mayor's office, the tricolor, same as the French flag. The sash is worn with

the blue always closest to the neck. Marianne looks down on every couple married

in France. The model for the statue is occasionally changed. Brigitte Bardot

and Catherine Deneuve have served as models. The mannequin and actress Laeticia

Casta, a favorite of mine, is the current model. The Marianne shown above is

an older model, probably turn of the 20th century. |

Does this strike you as strange? A mom marrying her son? I mean, I guess, doesn't

it sound a little risky? How about if the couple has a falling out, big arguments,

a divorce looming, and the wife shouts, "It's all your mother's fault,

I knew I shouldn't have let her marry us!" This could be the mother of

all mother-in-law problems.

In any case, the vows remain the same. It is only a five-minute ceremony. But

every mayor or deputy mayor and the secretary read from a script written and

approved by the National Assembly, their Congress. It has articles about this

and that and sounds like a boring legal contract. Most of the articles go back

nearly two hundred years, but occasionally there are changes and, to my astonishment,

I happened to stumble upon a recent one.

Fidelity is no longer required in France! And the couple doesn't even have

to live together!

The French have eliminated these two articles from the marriage contract. But

that's like bowing to the inevitability of pasteurized cheese and plastic-corked

wine, a stunning development.

The bride and her father lead the procession to the mayor's office. |

Of course, there has long been an article of hypocrisy attached to the marriage

contract. This is not Napoleonic times, and couples often spend months, even

years, living together before they decide to get married--if they marry at all.

The number of marriages have declined by 35 percent since 1970, and two of every

five children are born outside of wedlock.

While the terms of a legal marriage are strict, the French have always looked

on unmarried couples who live together with a gentle eye. "She is his concubine"

has something of a pejorative ring to it in English but not in French. Unmarried

couples can make an official declaration of concubinage--French is where

our English word comes from--and obtain almost the same benefits and rights

for themselves and their children as married couples.

There are no homosexual marriages in France--yet. But homosexual couples can

also make a legal declaration of their status and obtain some of the tax and

legal benefits of heterosexuals.

In fact, marriages are moving toward becoming a grand social ritual instead

of a flowery act fulfilling the need to legalize a couple's status in the eyes

of the state and public opinion. When I lived in Spain in the 1970s, some couples,

especially among gypsies, were still "showing the sheet." A couple

would hang their bed sheet out the window after their first married night together,

spotted with blood from the ruptured hymen, as testimony to family, friends,

and nosey neighbors that the bride was a virgin.

I run ahead of the procession to the mayor's office, where a crowd has gathered.

I see two guys holding a banner, blocking the door to the town hall. At first

I think it is some kind of demonstration. Are they protesting this marriage?

The French are forever demonstrating for or against one cause or another. This

is the only country in the western world where people still take to the streets

at the drop of a hat. Name it and they'll demonstrate against it.

I'm wrong.

The sign blocking the door to the town hall, above, reads: Emergency Exit--Follow

the Arrow. It is just a joke to tell the bride and groom this is their last

chance to escape from getting married.

Their young friends have brought other handmade signs which they pop up during

the ceremony and afterward.

"Last Chance"

"Too Late"

"The Pouting Begins"

The kids are having a lot of fun. The mayor's office is packed with them for

the ceremony, it is sweltering, and I can't elbow my way into a decent space

to take a photo. But it is over in five minutes and we join a honking motorcade

headed for the 17th century chapel, a couple of miles away, where the religious

ceremony is to be held.

This is the chapel where my wife Claude and her do-gooder group are raising

money for its restoration, and it is coming along quite well. Claude recently

picked up a charitable contribution of ten thousand dollars for the chapel,

which evolved after she played the Good Samaritan by stopping to help a woman

whose car had broken down. Give a little help, get a little help, you never

know.

| The crowd gathers at the chapel near Saint Sauvier for

the religious ceremony. The bride, Sylvie, near left, talks to the church

official who will perform the ceremony. |

|

When the bride and groom walk down the aisle to get married for the second

time, I hear music coming from a boom box.

What is that? It is certainly not the traditional wedding processional.

Now I recognize the music. Moby, the techno rocker.

Moby at a wedding--hmm, that's a bit too untraditional for me. I decide to

take my leave. Claude can fill me in on the ceremony.

The mayor of Saint Sauvier, Raymond Petitjean, and his wife, Marie Thérèse,

have become friends of ours. They loyally support Claude's fundraising

dinners for the chapel. As a matter of fact, that is where I first noticed

a difference between French and American politicians.

Mayor Petitjean, who is doing a little table-to-table politicking at

right, makes his own pear brandy, which is delicious. I've got a bottle

in my cabinet right now. It's not something that you want to drink much

of at a sitting, but his eau de vie puts a nice grace note on the

end of a fine dinner.

So the Mayor manages to chat up his constituents at the fund-raisers.

And then at the end of dinner he pours them a tiny glass of pear brandy.

Kissing babies maybe garner a politician votes in the United States.

But pouring brandy works in France.

The Mayor suggests that since I've already seen an unusual marriage, I might

want to see the standard issue, which means the town hall sort. Most of the

exuberant marriages take place on a Saturday in June, and I can sit outside

under the lime tree and hear sounds of honking motorcades fading in and out

from the surrounding villages. But many of the June weddings are quiet affairs,

with just a few friends and family crowded into the mayor's office. So I drive

to Saint Sauvier at noon one day to observe.

The couple look like they've known each other for some time. He is a carpenter.

She, from all evident signs, has a talent for cooking which he, from all evident

signs, muchly appreciates. Marriages have flourished on much less.

Before he begins the ceremony, Mayor Petitjean introduces me and asks the couple

if it is okay that I take photos. They look at me curiously and agree.

Then something happens that embarrasses all of us.

When they reach the point in the ceremony to present the ring, neither the

bride nor the groom can open the box. First, she struggles with it. Then he

grabs it and tries to rip the top off. It doesn't budge. Friends move up and

offer to help. What is this? A sign from heaven that this marriage shouldn't

take place? I suppose the struggle doesn't last more than three minutes. But

in that kind of situation, three minutes feels like three hours. Finally, as

if giving up, the box pops open.

After the fiasco with the ring, Mayor Petitjohn points a finger at me (above)

and jokingly admonishes me, saying, "Now don't you Americans go making

fun of us French." Then he hurries to finish the ceremony. Standing next

to him is Jacqueline, the town secretary and mother of the first bride in this

story.

Claude nudges me and whispers, "This would have driven your niece crazy.

Can you imagine?"

From the beginning of the first marriage, Claude has been drawing comparisons

to the wedding of my only niece, which we attended in South Carolina earlier

in the year.

"Yes," I say. "Barbara Dean would have hit the ceiling about

the stuck ring box. But let's get through this one and then we can talk about

the differences between the French and American way of marriage."

A French wedding leads to two important conclusions. The certificate of marriage

is signed by the couple. And then the mayor presents the couple with one of

the most important legal documents in France, the livret de famille,

a small record book for the registration of births and deaths in the family.

The marriage certificate is signed and witnessed by friends.

And that's it. Elaborate receptions are sometimes held, which last long

into the night. But many wedding parties repair to a local cafe for a few

drinks and a light lunch. |

. . .and a Third

|

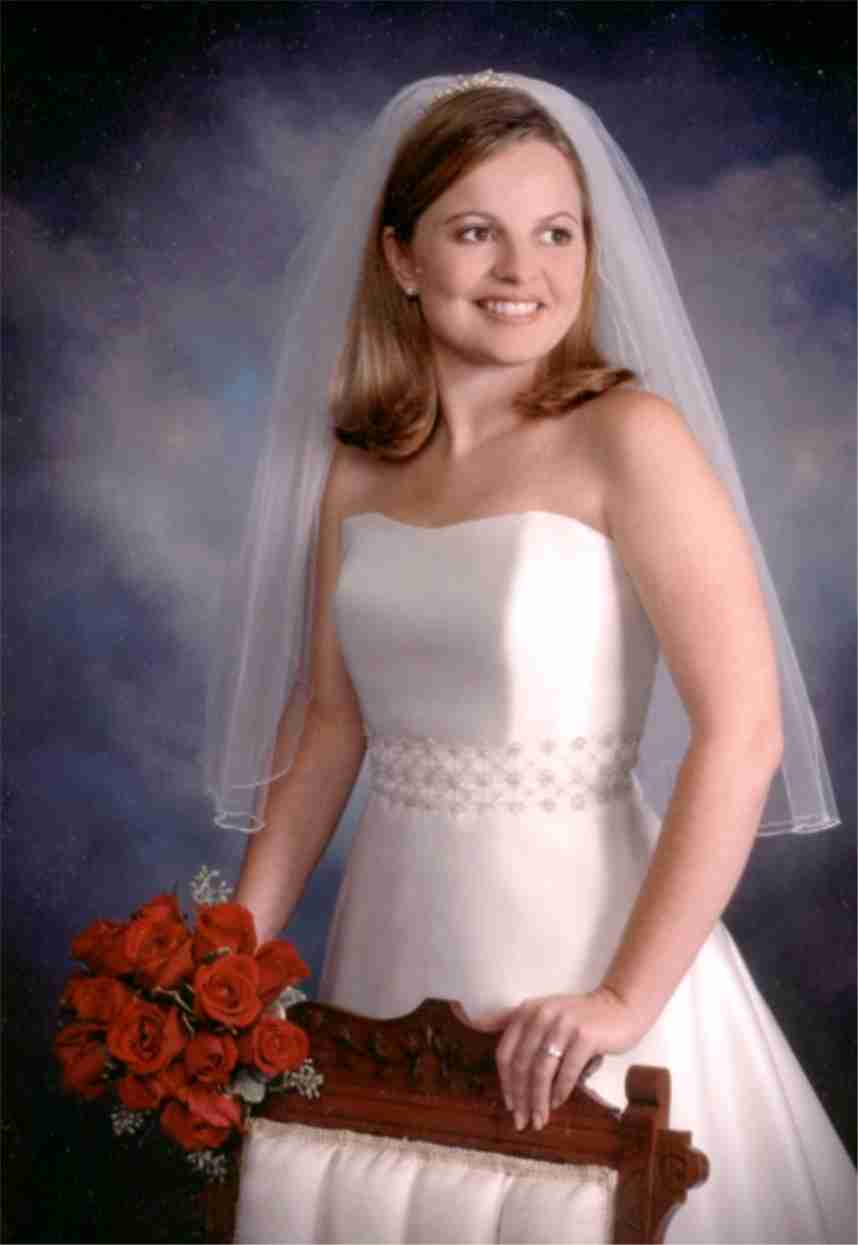

Barbara Dean Smith

Mrs. Jason Creel

January 18, 2003 |

Claude is bowled over by my niece's wedding. It's the first American wedding

she has ever attended that presents itself as a grand spectacle. It has been

planned down to the last tiny detail. A letter went out to everyone six months

earlier, giving the time and place and hotel information. The wedding program

itself is eight pages long. From the moment we arrive in Florence, SC, Claude

and sometimes I are drawn into the elaborate preparations leading up to the

event--wonderful food, cases of wine and champagne, a live band playing beach

music from the sixties, a reception or lunch for this, a reception for that.

It makes me dizzy.

"Is this the way all Americans get married?" she asks me.

"Not exactly," I say.

My niece, Barbara Dean, is a managerial pharmacist in Charlotte. She is one

of the most organized people I know. She is short and pretty, and as friendly

as a southern belle, but there's steel behind that smile, and I know everything

will start on time, there will be no stuck ring boxes here.

What strikes me is the way marriages have become such a big business in the

United States. When I was growing up there was maybe a bachelor party, a standard

church wedding, and a discreet reception afterward. But now you can find a paid

consultant to advise you on about anything. Lord knows how much Barbara Dean

spent for her wedding photo above--now taken before the wedding--and I learn

to my surprise that newspaper announcements of weddings are no longer free but

cost the bride and groom, at rates depending upon what they want.

In France the mayor's ceremony is free, a priest presiding at a religious wedding

is given a gift, and the church asks only for a minimum of $75, with extras

such as flowers added to the cost. French weddings are still cheap. But I look

on with amazement at my niece's wedding as I hear the cash register at every

turn--Ka-ching! I dare not ask the cost of this event. But I know it

has got to be beaucoup dinero.

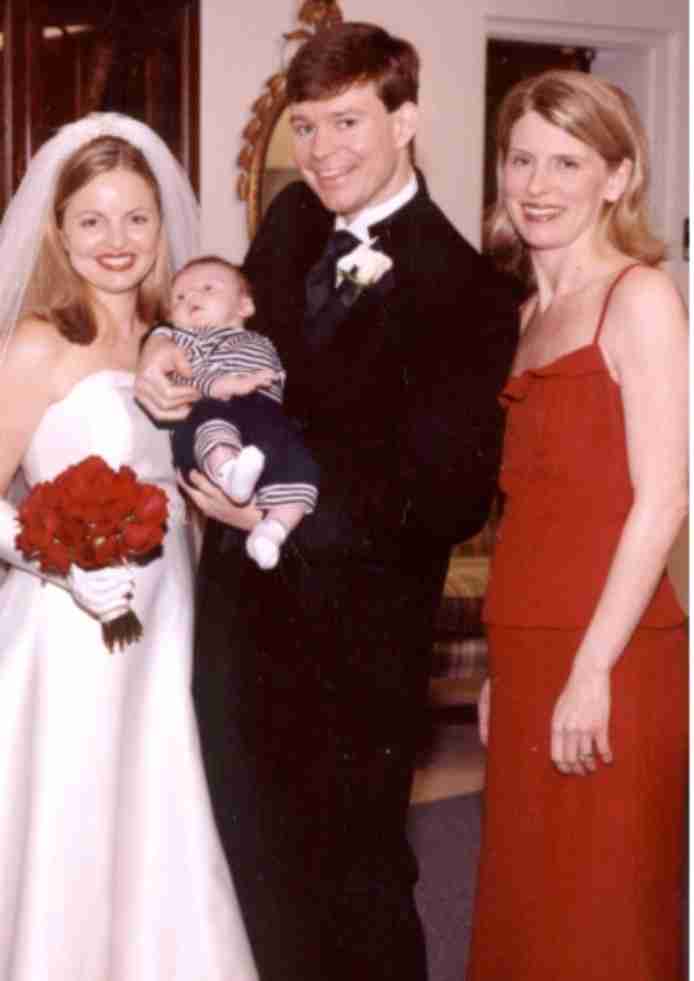

With Barbara Dean and my nephew James David--several years ago, it seems.

James David is one of SC's finest young lawyers. With his wife, Amy, right,

and their first-born, Grant. |

|

Left to right:

David, father of the bride, my sister T.D., Mrs. and Mr. Jason Creel, Claude

et moi. |

After the wedding, Claude asks to visit to Charleston, SC, before she returns

to our home in France. Barbara Dean and Jason are busy preparing to leave for

their honeymoon in the Caribbean but they volunteer to make our reservations.

When we arrive in Charleston we find that we are booked at the city's best hotel.

And the bill has been prepaid by Barbara Dean and Jason.

I should apologize right now for speaking skeptically about the high rising

costs of American weddings. If the bride and groom want to pay for a little

honeymoon for the uncle and aunt too, then I say bring'em on.

Thank you, Barbara Dean and Jason. Also thanks to Sylvie and Fabrice, Isabelle

and Serge, for letting me share their weddings. |