John McCain received mixed reviews from fellow pilots when he arrived on the USS Oriskany in 1967, a month before he was shot down and captured. Cal Swanson, commander of fighter squadron VF-162, was enthusiastic. Swanson thought McCain proved he had the right stuff by getting himself assigned to the Oriskany, an aircraft carrier sailing off the coast of North Vietnam in the South China Sea. The Oriskany had seen more combat and suffered heavier casualties than any ship in the Vietnam War. McCain’s own aircraft carrier, the USS Forrestal, had been put out of action by a horrific fire two months earlier.

After the Forrestal fire, McCain was assigned to Saigon as a navy PR aide. He was perfect for the job—handsome, charming, witty. He had met R.W. (Johnny) Apple, a well-known reporter for the New York Times, and Apple had smoothed his way in Saigon by introducing him to journalists and to the U.S. military and civilian command.

John McCain could have served out his tour flacking for the navy and having a lot of fun doing it—dining at Saigon’s French restaurants and hitting the bars full of pretty Vietnamese girls. But McCain wanted to get back into combat. He had completed only five missions before the Forrestal fire. Cal Swanson thought McCain’s attitude reflected well on his courage and patriotism.

McCain would not be joining VF-162, Swanson’s fighter squadron, however. McCain was not a fighter pilot, although in later years the media would perpetuate the mistaken belief that he was. Trained as an A-4 bomber pilot, he was assigned to attack squadron VA-163, which had an illustrious history. James Stockdale, a legend in the war, had commanded the squadron—and the air wing—before he was shot down and captured.

Still, a lot of pilots on the ship were not as enthusiastic as Swanson about McCain. They were not really convinced that he had the right stuff. Naval aviation was a small, tightly-knit community made up of highly-trained men with large egos and a fiercely competitive nature. Even if they did not know each other personally, everybody was linked together via the gossip hotline, and McCain’s reputation had preceded him to the Oriskany.

Some of the negativity was not his fault. His family background was bound to stir skepticism and jealousy. McCain’s grandfather had been a highly-decorated admiral in World War Two. His father, John S. McCain II, also an admiral, would soon become commander-in-chief of all forces in the Pacific, making him the highest ranking officer in the Vietnam War.

In military terms, John Sidney McCain III was born with two silver spoons in his mouth. It was something he evidently considered later in life to be both a blessing and a curse.

Nevertheless, McCain had acted as though he was determined to show all those who were inclined to think the worst of him that they were right. As he wrote in his book Faith of My Fathers, “I did not enjoy the reputation of a serious pilot or an up-and-coming junior officer.”

His record as a midshipman at the U.S. Naval Academy was dismal. He piled up demerits left and right for breaking the rules, and barely passed his schoolwork, graduating 894th in a class of 899.

That might have been checked off to youthful rebellion. Plenty of kids spent their college years partying but then sobered up after they were slapped in the face by the reality of making it in the outside world. But after he left Annapolis, McCain continued to show the same attitude that had almost got him kicked out of the naval academy.

He barely passed flight school. And then he crashed two airplanes and damaged a third.

The first crash took place during advanced flight training at Corpus Christi, Texas. According to McCain, the engine stalled while he was practicing landings. The plane fell into the water of the bay just off the airfield and knocked him unconscious. McCain woke up and somehow managed to get out of the cockpit and escaped serious injury. Investigators reported that they started the recovered engine without any problem, and their report left open the possibility of pilot error.

The next accident took place in Spain while McCain was assigned to an aircraft carrier in the Mediterranean Sea. He tried to fly his propeller-driven A-1 fighter-bomber under a row of pylon-supported electric power lines. This was a “hotdogging” stunt by U.S. pilots in Europe that had caused outrage. McCain’s plane hit and damaged the lines so badly that thousands of people lost power.

“My daredevil clowning had cut off electricity to a great many Spanish homes,” McCain wrote later, “and created a small international incident.”

In 1965, McCain flew a navy airplane to Philadelphia to attend the Army-Navy football game. On the way back to his base in Norfolk, Virginia, the plane’s engine quit, he said, so he bailed out. The plane crashed and was destroyed.

In the U.S. Navy, for a pilot to crash one plane was pushing it. To crash two often resulted in an official investigation to determine if he should be taken off flight status. How McCain got away with crashing two airplanes and smashing power lines in Spain was a mystery, although other pilots thought it had to do with his family connections.

McCain volunteered for Vietnam and was assigned to an A-4 bomber squadron on the USS Forrestal. He was soon to be 31 years old and held the rank of lieutenant commander, equal to that of army major. On the morning of July 29, 1967, McCain was sitting in the cockpit of his Skyhawk waiting to be launched by the ship’s catapult. Another plane accidentally set off a Zuni missile that hit the fuel tank of McCain’s A-4, touching off a fire that spread rapidly across the ship. McCain managed to escape injury, but 134 sailors died and many others were badly burned.

It was the worst U.S. Navy accident since World War Two and the fourth serious accident McCain had been involved in since becoming a pilot. His reputation for being a “hotdog”—a show-off pilot who broke the rules—led to rumors that McCain had caused the fire by trying to scare the pilot behind him by suddenly shooting flames out of his tail exhaust. There was no evidence McCain was at fault and the fire was ruled accidental. But the rumors persisted.

|

| The USS Forrestal fire was the worst naval accident since World War II. It started after a rocket hit John McCain's plane. |

|

McCain also developed a reputation for volatility. He was a fun-guy and made friends easily. But he lost friends easily, too. He had a quick temper and was prone to flare up over minor incidents. As his best friend from the early years said, “John could piss people off.”

McCain’s squadron on the Oriskany was composed of 15 alpha males who spent most of their time when they weren’t flying or sleeping in a ready room no bigger than a medium-sized living room at home. Above all, they admired officers who remained cool and calm under all circumstances. McCain’s squadron commander, Bryan Compton, was considered the ideal officer, though no one wanted to sit near him in the ready room because the flight suit of “Magnolia,” as the squadron called him, usually smelled to high heaven.

“I would have followed Bryan Compton anywhere,” said Dick Wyman, a pilot in Swanson’s squadron. “He was the kind of guy the worse things got, the better he was. He was the ugliest s.o.b. you ever saw. But he was our shining star.”

McCain called Compton “one of the bravest, most resourceful squadron commanders, one of the best A-4 pilots in the war.”

In any case, Oriskany pilots did not have time to pay much attention to the admiral’s son, because the ship was running bombing operations against North Vietnam on a 24-hour schedule. The Oriskany was a small and undistinguished carrier, commissioned at the end of World War Two. Nobody could explain why the ship had turned into the leading combat carrier of the Vietnam War. It was as though the runt of the litter had grown into a pit bull.

The squadrons on the Oriskany were front-loaded with lieutenant commanders like McCain and it was do-or-die time for them in terms of promotions. This doubtless accounted, at least partly, for the carrier’s aggressiveness. These were seasoned professional officers and only the best and bravest would be promoted to the next higher rank of commander (lieutenant colonel) and very few to captain (colonel).

The pilots watched each other like hawks, trying to stay even in the number of missions flown over North Vietnam. Always ready to take the risks, they developed tactics to survive the surface-to-air missiles and antiaircraft fire they faced every time they went on a mission. In a war, of course, there was always the factor of luck. Sometimes you just couldn’t avoid getting shot down.

But their tactics worked surprisingly well. To evade SA-2 missiles (SAMs), the pilots used a maneuver to confuse the missile’s guidance system. An American electronics plane was flying off the coast during the attacks. When it intercepted the missile’s guidance signals, the plane alerted the pilot as to whether a SA-2 was headed toward him by sounding a tone in his headset.

“If we thought the SA-2 was homing in on us, we would try to keep our speed up until the missile was several seconds away and then barrel roll on our backs and pull vertically down,” said Roger Duter, a bomber pilot on the Oriskany with McCain. “At that time the missile was moving too fast to follow us down and we would recover and resume our course to the target.”

Since the SAM maneuver always worked if executed properly, the biggest danger came from the fire of antiaircraft artillery (AAA). The pilots used the tactic of weave and zigzag to keep from flying into the path of the exploding flak.

“We lost more aircraft to AAA than SAMs, though the SA-2 seemed more threatening from a personal point of view,” Duter said.

All pilots were taught the tactics to keep from getting shot down. To the American public, every pilot brought down by enemy fire was a hero. But carrier pilots made a sharp distinction between someone who was unavoidably shot down and a pilot who simply made a mistake.

Everybody on the ship, for example, liked a lieutenant commander who was shot down twice and rescued. But it was widely believed that his second shoot-down had occurred because he made a mistake. They still liked the pilot, he was friendly and capable, but everyone said, “Hey the guy screwed up. He got himself shot down.” The incident hindered his chances for future promotion.

The pilots had one big gripe. They thought they were risking their lives to hit insignificant targets. The Pentagon, in its exaggerated press releases, made the targets sound more important than they were. North Vietnam was an agricultural country and did not have a big industrial sector. Besides that, President Lyndon B. Johnson closely controlled what targets could be hit and he usually ruled out anything in Hanoi.

So on October 26, 1967, the scheduled attack on the thermal power plant in Hanoi threw the Oriskany into a state of excitement. This was going to be a big one for McCain and everybody else. Bryan Compton had led a daring raid on the plant six weeks before McCain arrived and won a Navy Cross for the mission. But the power plant had been repaired by the North Vietnamese and was again on the target list.

McCain pleaded with his squadron’s operations officer, Jim Busey, to be assigned to this new attack. The operations officer had nicknamed McCain “Gregory Green-Ass” because he had flown far fewer missions than the other pilots—only 22. At first, Busey resisted, but finally he gave in to McCain, who always charmed or cajoled to get his way.

Another “new guy” was also going on the mission to hit the Hanoi power plant. Lieutenant Junior Grade Charles D. (Chuck) Rice, 24, had arrived on the Oriskany one month before McCain and had flown 36 missions. Rice, whose dad was a TWA pilot, was assigned to Swanson’s squadron as Dick Wyman’s wingman. Wyman, who was one of the best pilots on the Oriskany, literally took Rice under his wing to keep him from getting shot down.

Rice recalled: “I said to Wyman when I got there, ‘Dick, I don’t know what I’m doing.’ Dick said, ‘I know. You just stay on my wing and do what I do. Don’t lose me. Just forget about everybody else.’”

Unfortunately, Dick Wyman would not be there to protect Chuck Rice on October 26, 1967. Shortly after take-off, Wyman’s generator went down and he had to turn back, leaving Rice to fly with two other F-8 pilots from Squadron 162.

The attack was scheduled for around noon and the pilots went for an early lunch of pork chops. The Oriskany was known for its good food and Rice and his friends figured they would be back in time for a second helping of pork chops, since a round-trip mission to Hanoi took only about an hour and a half.

The mission was called an Alpha Strike, a designation used for only the biggest and most important attacks on North Vietnam. Burt Shepherd, the air wing commander, led the strike group. It included 20 aircraft from the various squadrons on the ship. As the strike group went over the beach, the North Vietnamese were waiting. They fired 22 SAMs at the Americans and unleashed a torrent of antiaircraft fire. For the pilots, it took a cool head to evade missiles and AAA being fired at them at the same time.

“I recognized the target sitting next to the small lake from the intelligence photographs I had studied,” John McCain recalled in Faith of My Fathers. “I dove in on it just as the tone went off signaling that a SAM was flying toward me. I knew I should roll out and fly evasive maneuvers. . .But I was just about to release my bombs when the tone sounded, and had I started jinking [maneuvering to evade the SAM] I would have never had the time nor, probably, the nerve to go back in once I had lost the SAM. So, at about 3,500 feet, I released my bombs, then pulled back the stick to begin a steep climb to a safer attitude. In the instant before my plane reacted, a SAM blew my right wing off. I was killed.”

By his own admission, then, McCain failed to follow instructions in combat. He did not try to evade the missile. Moreover, the pilots who were flying near him, one of them with a handheld camera, said he was not hit by a SAM. He had flown too low and was brought down by a barrage of antiaircraft fire. Since a SAM exploded in a bright orange fireball visible for miles around, it was unlikely that they had called it wrong. And since official navy records listed John McCain as downed by AAA fire, they were puzzled by why he later insisted in his political campaigns that it was a SAM.

As other pilots saw it, John McCain, quite simply, had got himself shot down.

But McCain also made another error in the next four to six seconds after he was hit. He failed to use the proper procedure he had been taught for ejecting. As a result, he injured himself critically, breaking both arms and his right leg.

Chuck Rice got shot down at the same time as McCain. Rice was hit at 12:48 p.m. After Dick Wyman had to return to the carrier with a mechanical problem, Rice continued to fly as the wingman for one of the other two pilots from 162, his roommate Ron Coalson. When Coalson made a turn, Rice fell behind him.

“Why’d I get slow?” Rice said. “Because I was stupid. I was looking around and got distracted.”

Rice was trying to catch up when Coalson radioed, “Chuck, you got one at ten o’clock.”

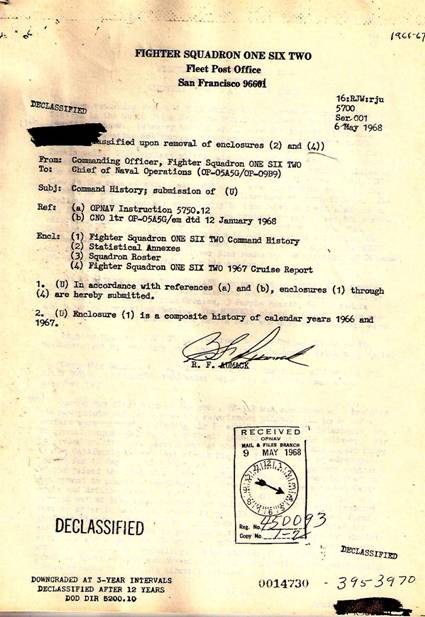

|

| Cover sheet for the 1967 Command History of VF-162—Chuck Rice’s fighter squadron. |

|

| The U.S. Navy report of Chuck Rice's shoot-down. (No.7) John McCain was in the other aircraft downed at the same time. |

Chuck Rice looked to his left and saw a missile headed at him. Then he saw another SAM fired right behind the first one.

“I started the maneuver,” Rice said, “I was doing what I was supposed to do, flying an arc around it with a barrel roll. The first one went by and it looked like a telephone pole, that’s how close it was. I didn’t even get my wings level when the second one just blew my airplane to hell.”

The plane burst into flames, burning Rice’s arms. His left wing was blown away. The plane went into a spin and rocked so violently that Rice couldn’t grab the ejection handle which would trigger an explosive charge to shoot him out of the cockpit and open his parachute.

“Holy shit!” Rice said aloud. “You’re going to die.”

Rice knew that if he ejected without first putting himself in the proper position, as he had been trained, he risked injuring or even killing himself. The cockpit was small and as tight as a metal holster. Not ejecting properly meant he would hit the plane’s sides as the ejection charge propelled his chair up and out of the cockpit. The chair then separated from his parachute.

“I tried to reach for the ejection handle,” Rice said. “But the plane was shaking so violently that I couldn’t get a hold of it. I put my left hand on the radar scope and threw my shoulders back against the seat so it wouldn’t rock. With my left hand braced, my head held down, I grabbed the ejection handle. I was thinking, ‘You’re going to break your back but you are going to get out of here.’”

Rice ejected without injury. With cool thinking, he had forced himself into the proper position for the ejection.

“The next sensation I felt was just violent tumbling,” Rice said. “Then I looked up and here I am with a chute. And the worst despair I’d ever felt hit me at that moment. I started crying. I said, ‘This can’t be happening to me!’ Floating down. Tears coming out of my eyes.”

By comparison to Rice, McCain described his ejection like this:

“I reacted automatically the moment I took the hit and saw that my wing was gone. I radioed, ‘I’m hit,’ reached up, and pulled the ejection seat handle. I struck part of the airplane, breaking my left arm, my right arm in three places, and my right knee, and I was briefly knocked unconscious by the force of the ejection.”

Without adding context or further explanation, McCain and his co-author Mark Salter left it to sound like breaking two arms and a leg during an ejection was a fairly routine occurrence. In fact, it was an error that McCain would pay for with his resulting bad health.

Chuck Rice landed near a group of militia. He pulled out his pistol, prepared to fight, but when he saw he was outnumbered he surrendered. He was taken to Hoa Lo prison—Americans called it the Hanoi Hilton. At his first interrogation he refused to answer any questions.

His interrogator said, “Well, I guess it is time to begin.”

“Two men entered the room,” Rice said. “Their basic method of torture was to tie you up where you were eyeball to eyeball with your ass. They put shackles around my ankles and then ran a bar through the shackles to spread my legs. They brought a nylon strap over my back, put it under the bar, and pulled the bar up until I was forced into a ball, straining every muscle in my body.”

John McCain landed in Truc Bach Lake, in the middle of Hanoi. He managed to make it to the surface and inflate his life vest, then he blacked out.

“When I came to the second time, I was being hauled ashore on two bamboo poles by a group of twenty angry Vietnamese,” he wrote.

Actually, as the Vietnam Government and an American veteran living in Hanoi confirmed years later, Mai Van On, 49, a Hanoi resident, ran from the safety of his bomb shelter and with the help of a neighbor tossed two bamboo poles in the water and swam out to rescue McCain. Mai Van On and his friends floated McCain to shore, where they were confronted by an angry mob which wanted to kill the American. One Vietnamese smashed McCain’s shoulder with a rifle butt and another stabbed him in the foot and abdominal area with a bayonet before Mai Van On and his friends could drive them away.

In all probability, McCain’s life was saved by his Vietnamese rescuers, although this was a point apparently not convenient to his later political biography.

|

| John McCain being saved from drowning. The Vietnamese on the left, probably Mai Van On, holds his arm. McCain was confronted by an angry mob when he reached shore. |

McCain was candid, though, in admitting that the injuries caused by his ejection, particularly his broken knee, drove him to try to bargain with his prison interrogators. He told them he would give them information if they took him to a hospital. He claimed he didn’t really intend to keep his word. But very soon he, like Chuck Rice, like James Stockdale, like every American POW in Hanoi, was broken. McCain did what the North Vietnamese ordered: He signed and made taped statements that could be used as propaganda against the United States of America.

There was no question that McCain was beaten and underwent torture and that he suffered a brutal experience. But as he put it in Faith of My Fathers:

“I also suspected that my treatment was less harsh than might be accorded other prisoners. This I attributed to my father’s position, and the propaganda value the Vietnamese placed on possessing me, injured but alive. Later, my suspicion was confirmed when I heard accounts of other POWs’ experiences during their first interrogations. They had endured far worse than I had, and had withstood the cruelest torture imaginable.”

Ironically, John McCain became the beneficiary of his own mistakes as a pilot when his political career took off. He continued to claim that he had been shot down by a surface-to-air missile, when the official record said he had been downed by antiaircraft fire. The American public knew the SAM as a most terrifying weapon—but not about the evasive tactics pilots used to avoid the missiles.

“I guess the SAM sounds better but I think it is a moot point,” said a pilot who served with McCain.

Most surprising were the political benefits that accrued from his ejection injuries. The TV shots of a hospitalized McCain, or a McCain hobbling around on crutches, became associated in the public mind with the American hero who had been severely tortured. The public assumed that was the reason he was in such bad shape.

On the day they were both shot down, Chuck Rice was as shocked and as scared as John McCain. His plane was damaged in the same way and at the same time. Yet Rice had figured out under tremendous pressure how to eject without getting himself killed or injured. Just as most other pilots had figured it out when they were shot down. It left a question: Why wasn’t LCDR John S. McCain, 31, able to put himself in the proper position to eject like LTJG Charles D. Rice, 24, who had much less flying experience?

Another public misperception arose concerning McCain’s refusal of an early release offered to him by the North Vietnamese. In reality, John McCain was not the singular POW who, as Time magazine wrote, “languished in prison in Hanoi for years rather than accept a release he considered dishonorable.”

In fact, McCain, as part of a still functioning U.S. military chain of command, had three choices. One, he could ask his American senior ranking officer at his prison for permission to accept an early release and abide by his yes-or-no decision; two, he could decide on his own to violate regulations against accepting an early release and possibly face censure when all POWs were freed. And, of course, he could have quickly said no to the offer.

This was not about John McCain’s honor, as he later made it appear, or about his personal struggle as to whether to accept an early release. (Which the North Vietnamese also offered to other POWs as a propaganda ploy.) It was about his sworn duty as a lieutenant commander in the United States Navy. In that respect, McCain was no different from the 590 other Americans held by Hanoi.

The POWs had set up a military organization with a communication system based on a wall-tapping code. The prison leaders were selected in the same way leaders in any U.S. military organization were selected—by rank and date of rank. McCain was duty-bound to follow orders sent down by his superiors in the chain of command. One of the first orders established the rules concerning an early release.

The prison command system did not work smoothly until near the end, when all the POWs were consolidated at the Hanoi Hilton. If the Vietnamese identified any leader or caught anyone communicating with another prisoner, they were severely beaten and put in solitary confinement.

But McCain knew that Air Force Colonel Ted Guy was his senior ranking officer during the time he spent at a prison camp called the Plantation. Guy was such a stickler for discipline that he brought charges against several POWs after the war for collaborating with enemy. (The charges were later dropped.) Guy stood firmly against anyone taking an early release—except for one person, as he later stated in a book about POWs called Survivors.

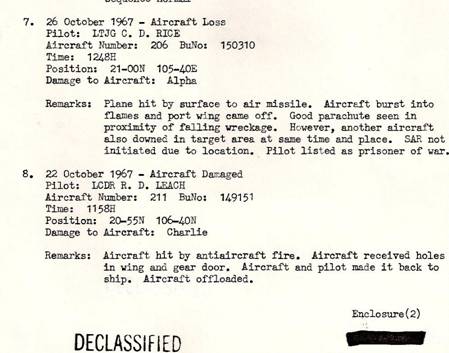

|

| Col. Ted Guy was McCain’s\ Senior Ranking Officer (1974) |

“I felt that no one should go home regardless of date of rank or how long held,” Colonel Guy said. “There was one man at this time who I thought was sick enough to accept release—John McCain, Admiral McCain’s son; he was badly wounded.”

McCain did not ask Guy for permission to accept an early release, and may not have been aware of his SRO’s attitude. But the point was that, under the military system, Air Force Colonel Guy had the authority to decide whether Navy Lieutenant Commander McCain could accept an early release—not McCain himself. So McCain’s personal struggle over the decision, which he described with such emotional detail in his book, was irrelevant to the true situation, unless he had chosen to violate regulations and put himself at risk for future censure.

Wesley Clark, a retired army general, was widely reviled in the media when he said during McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign that getting shot down did not qualify anyone to be president.

As for the truth of his proposition, one only had to look to the greatest hero to come out of the Vietnam War—Admiral James Bond Stockdale who, as even McCain would have to admit, stood head and shoulders above him as a pilot, as a POW, and as a winner of the Congressional Medal of Honor. However, Stockdale had proved to everyone, and even to himself, that his war experiences did not necessarily qualify him for high political office when he ran in 1992 as Ross Perot’s vice presidential candidate.

On the other hand, the converse to Clark’s proposition was equally true. Getting shot down did not disqualify anyone to be president. But it did show whether a pilot had the right stuff.

Footnote: To see how official records list McCain’s shoot-down, click http://www.a4skyhawk.org/2d/skyhawk-casualty.htm

|

LCDR John Sidney |

26. Oct. |

A-4E 149959 (VA |

struck by |

McCain |

1967 |

163) |

AAA |

_______________________________________

ZALIN GRANT volunteered for Vietnam and served as an army officer. A former journalist for Time and The New Republic, he is the author of four books on the war including OVER THE BEACH: The Air War in Vietnam and SURVIVORS: Vietnam POWs Tell Their Stories.

Copyright © 2008 Pythia Press

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

| Fighter Squadron 162 on the USS Oriskany 1967. Three members were with John McCain the day he was shot down. Cal Swanson is center, kneeling; Dick Wyman fourth from 0left, second rank. |

|

|