Gamel Woolsey, then in her late thirties, was living in a small village outside the southern coastal city of Malaga when the Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936. She had arrived in Spain four years earlier with her English husband Gerald Brenan, who had published little at that point, but who was to become a highly acclaimed writer on Spanish history and culture. Gamel Woolsey, then in her late thirties, was living in a small village outside the southern coastal city of Malaga when the Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936. She had arrived in Spain four years earlier with her English husband Gerald Brenan, who had published little at that point, but who was to become a highly acclaimed writer on Spanish history and culture.

Gamel Woolsey and Gerald Brenan considered themselves poets first and novelists second. Nonfiction writing ran a distant third in their literary aspirations, although this is where both of them were to excel. Gamel Woolsey was particularly of a poetic temperament, and when she turned her sensitive eye on the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, she produced what is simply one of the best--though least known--books on that conflict, distinguished not for its "facts" but for an emotional truth found at a much deeper level.

Gamel Woolsey instinctively understood that a civil war, with all its irrationality of blood killing blood, could not really be told by a journalistic recitation. She did not even bother to give any dates, except to make vague references to the months during which her story takes place, July through October of 1936. Nor did she provide many details about the confusing multitude of political parties on the left and right, the competing ideologies of the war, which George Orwell described as "a plague of initials."

Yet through her character sketches and personal observations a reader comes away from Gamel Woolsey's book with the feeling that he or she has attained an instinctive grasp of the Spanish war, as great, perhaps, as if one had plowed through some multitomed work heavy with facts and statistics. And not only with a feeling for the war--but for Spain itself, especially those warm and dignified people of Andalusia, the country's poorest region, where the book is set. Her descriptions of Spain are timeless, therefore remain as fresh and compelling today as when written.

Here is Maria:

"Maria was tall and rather thin and still handsome at fifty-four, which is old for a Spanish woman. Her thick hair was still black and her smooth olive skin tightly drawn over the strong bones of the face...she was hard upon mankind in general and spent a great deal of time in disapproving. Novedad--Novelty was her horror. Anything new was suspect. She would not have had a leaf change. "

And Pilar:

"I do not think Pilar had ever been at all in love with Antonio: he was really a very dull young man. But his attachment had been the greatest pleasure of her life. And it had given her dignity and value in her own eyes. It had been a late, thin blooming after many barren lonely years. And now it was over ."

Her account of life in Spain is exquisite. On irrigating the garden:

"We would watch with a sort of fascination the water beginning to bubble up in the middle of the flower beds, just where Enrique wanted it, from pipes that ran from bed to bed; and then the watering of the fields, a carefully directed stream down the first furrow until that was full, and then a few clever strokes with a hoe, a little dam built here, a new passage opened there, and the water streaming down to fill another furrow, led off sometimes by small canals to fill little moats around the fruit trees which stood in rows along the high orchard wall."

Spaniards have always presented the outside world with a problem, more so than any other Europeans. How do you capture their essence? We rely on stereotypes and thus feel comfortable with the French who, we think, are arrogant but logical and stylish; and the Germans, who are efficient but humorless and a bit large.

But Spaniards--what of them? Outsiders tend to be either overly critical or overly sentimental when they write of these complex people. The result is often caricature.

But Gamel Woolsey--and of course Gerald Brenan too--wrote about Spain as though she were using a carpenter's level. The affection is clearly there, but, more, an understanding, and an unwavering gaze into the depths of Spanish nature.

The Spanish Civil War does not lend itself to easy synopsis. For the reader to whom this cataclysmic event has become, as Gamel Woolsey presciently saw it sixty years ago, "a dim half-forgotten story of old tragedy," it will suffice to remember only the bare outlines of the conflict to appreciate her story.

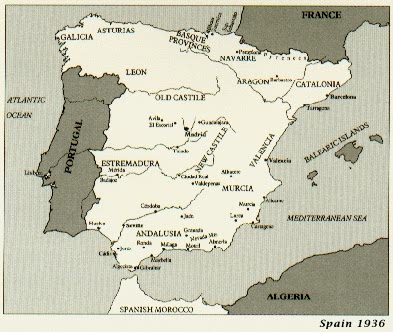

In February 1936, the multitude of leftist parties, ranging from communists and socialists to the anarchists, were temporarily united and swept into electoral power under the banner of the Popular Front. In this volatile mixture of leftism, the communists could be considered almost conservative. The anarcho-syndicalists, who controlled Malaga and the village where Gamel Woolsey lived, were the most radical. They called for violent revolution and the seizure of private property. For the first few months, during the period when this story takes place, the anarchists held the upper hand in the left's ideological battles. But as the war went on they were displaced by the communists and the socialists.

The right was more easily pinpointed--and more united. Made up of the army, the aristocracy, the Catholic church, and the landowners--that is, the entrenched order and the wealthy class--the right was frightened to its roots by the success of the Popular Front, and started plotting a revolt to regain power. It began when the generals, led by Francisco Franco, mutinied against the Republic and touched off the civil war in July 1936, using the greatly feared Moorish (Los Moros of Gamel Woolsey's account) troops from Morocco, along with the Tercio, the Spanish Foreign Legion, as their hammer.

Although the civil war was portrayed, especially by European and American intellectuals, as being a struggle between Fascism and Democracy, between darkness and light, it turned out to be--as George Orwell and Gamel Woolsey recognized early on--not quite that simple. The revolution from the right produced the sparks for the already simmering revolution from the left. What took place for the next three years was a bloody struggle that sometimes pitted families against families, friends against friends, but mostly have-nots against the haves.

The haves won. And Franco instituted a repressive dictatorship that was only ended with his death in 1975.

"He is finally dead," one of Franco's doctors says to another, ran the Spanish joke at the time. "Yes, but who is going to tell him?" asks the other.

Thus in this case, unlike most other revolutionary conflicts of the 20th century, the rebels were the conservatives and fascists. The leftists--communists, socialists, anarchists, trade unionists--were the legal representatives of the Madrid government, the Republic.

All of them were equal in Gamel Woolsey's eyes; she felt a profound sympathy for the Spanish people caught up in this bloody conflict--not for the politics of the left or the right. That's why her work stands the test of time. |