|

|

THE BEGINNING: A Funeral |

I was worried about the weather. A cheerful man should not be buried in depressing circumstances, and the forecast on Saturday, February 5, 1994, was for snow.

Panou had not been embalmed, the French don't do that, just taken home after spending twenty-four hours in a nearby hospital cooler (a 3-hour minimum required), while the French bureaucracy satisfied itself that he was truly dead, stamping and fondling various official forms; and then afterward he was released and driven to the farm, to be laid out in the same bed in the same room where he had slept for more than thirty years. He was dressed in a blue suit and red tie; the bed covers were pulled back to reveal his hands folded over his chest.

It grew colder, started sleeting. The funeral, I knew, could not be postponed because of bad weather. Panou deserved better. |

Panou at age 19, in 1925. |

Henri was his name but family and friends called him Panou (pan-noo). Before cancer got him a month short of his eighty-eighth birthday, Panou still had all his teeth, an eagle's vision, a good head of gray hair, and a smile that seldom left his face. He was blue-eyed and handsome, a slim six-footer who walked ramrod straight and seemed even taller.

But wait a minute, before this begins to sound like I'm going to run on about what a wonderful guy Panou was, maybe I should reveal some really shocking things about him. For instance: The day he seemed ready to attack me with his cheese knife.

The Brie was passed at the dinner table, I did what I thought was expected of me. Panou's face turned red, his shoulders heaved in outrage. "What," he asked sharply, "did you do to our cheese?" "I took a slice, Panou," I said.

"No!" he said, almost rising from his chair. "You cut off the nose!"

Being American, I thought there was no requisite way to slice cheese. I had cut it horizontally. Guilty as charged: I had cut off the Brie's nose. And Panou seemed ready to say, "Off with your head!"

Actually, that's the only shocking thing I can remember to tell about Panou, and I only recall this incident because it stands out for being so extraordinary, for Panou never raised his voice, was as kindly-natured and as generous-spirited as anyone I've ever known. It just happened, though, that food and how you treated it was a very important issue in Panou's house--very important. One did not cut off the nose of a cheese.

So yes, I am going to run on about what a wonderful guy Panou was. But it's only fitting that I begin these Letters from a French Village by telling about him, because Panou was the reason I came to live here, in the center of France, five years ago. He had raised two daughters. The first, Yvette, died an untimely death at a young age. The second, Claude, was the heir to the farm that Panou had nurtured with such love and tenderness. Claude is my wife.

The weather turned better at the last moment. It was still very cold but the sun lit up the grayness of the February morning and the icy rain stopped. Someone was looking down on Panou.

Transferring Panou to his shiny oak coffin with the gold cross on top was a quiet but casual affair. The postman, visiting to pay his condolences, was called upon to assist. The funeral director, who looked about thirty-two, had arrived alone in his gray Citroën hearse. He had begun in the village as a carpenter and coffin maker, and his wife sold flowers. He was dressed in a blue blazer and was cheerful, not falsely solemn in the least, just the way Panou would have wanted it.

Nothing could be colder, I think, than a funeral held in an unheated French church built nine hundred years ago. We arrived at three p.m.--the church was two kilometers from the farm--while the bells tolled. The whole village turned out, Panou was much beloved. The church was cloudy with condensed breath.

The priest, stolid, perfunctory, recited his liturgy. Behind him, in a semi-circle left to right, stood eight veterans of World War Two, holding the tricolor and their battle flags. Panou was a genuine war hero--although he would have thrown his arms shoulder-high, palms turned outward, and issued a dismissive "Bah!" if he'd heard me make such a claim. He had served as a sergeant major in the French army, was captured, escaped from a German POW camp, and returned to join the Resistance. He was written up in a history of the war.

In fact, as so often happens between men, war was an important bond between us. My father had also served in World War Two, as a master sergeant in the most decorated U.S. infantry regiment of the war, and had been critically wounded at the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium, December 1944, saved because another soldier kicked his body, half buried in the snow, and saw the quiver. I'd passed five years in the Vietnam War, first as an army officer, then as a journalist. |

Panou in battle gear during World War Two.

He was an authentic war hero, though he would have said "Bah!" if he heard me make the claim. |

|

My father (center)in a French village, mid-1944. His two friends were later killed in Belgium and my dad was seriously wounded. He recovered in a Paris hospital, and always spoke highly of French nurses. |

|

Panou learned from war what my father learned, what I learned, what all men learned. In World War Two, Vietnam, any war, it was the same, Panou said: The wrong people usually got killed.

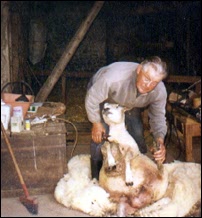

As the priest dutifully plowed through the service, I thought of American funerals I'd attended, of how friends and relatives were invited to talk about the deceased, to give eulogies that often wound up as effusions about themselves, and I began to compose what I would say about Panou. I would tell about his cherished garden, fully 50 meters long and 30 meters wide, about his rabbits, chickens, his sheep, about how he cut hay for his neighbors, loaned them tools, even tools that he knew might not be--sometimes weren't--returned. |

Panou at sheep shearing time, 1984. |

But I was awaken from my reverie when the priest began to swing his smoky censer, and then I found myself in the line filing past to make the sign of the cross with holy water over Panou's coffin. It was as if I were in a daze. I realized that I hadn't understood a word of what the priest had said about Panou. Had my French deserted me at this moment?

I overheard two women in front of me whispering as I walked out of the church.

"I didn't understand a word of what he said," one whispered.

"I didn't either," the other said.

The priest was retired, a stand-in who had been called at the last minute because the village curé was already committed to another funeral. He had a speech impediment.

Then I heard Panou's voice in my ear: "Allez, allez, let's hurry home for a glass of wine."

I knew he was smiling. |

| RECIPE ONE |

Panou's Omelette

To write from a French village and not talk about food would be like writing from Siberia and not mentioning snow. Despite the rise of American-style supermarkets and the spread of McDonald's to the four-corners of the country, the French attitude about food remains...well, it remains uniquely French, especially in the countryside. Not only is food a source of life but a source of joy, a source of rapturous conversation, of competition to find the freshest, the tastiest, to serve the best.

Panou was not a particularly good cook, although he was surrounded by--and appreciated--wonderful food his whole life. He was celebrated for providing the ingredients that go into good cooking, the vegetables, the spices--he grew potatoes that would make you do the gustatory equivalent of a double-take. Whaaa? A lowly potato can taste that good? As his daughter Claude likes to say, Panou was an organic gardener before the term was invented. |

Panou in his garden, 1991. With typical generosity, Panou was growing American sweet corn especially for me--although he never ate corn in his life, nor did anyone in his generation. The French considered corn strictly a food for animals. Corn on the cob has nudged its way into some French homes in the past few years, but it is usually found already shucked and under plastic in supermarkets, and is still considered a novelty. |

Panou's speciality was l'omelette aux pommes de terre--a potato omelette--and he made it like no other I've tasted. Panou was a sort of survivalist before that term too was invented. He had gone through the hard times of economic depression and war, and he believed that if you were able to raise a few chickens and grow some potatoes, you could survive anything. It was a philosophy that came from his grandmother, who taught him how to cook the potato omelette. Which means this recipe goes back at least to 1840.

I asked Claude to duplicate her father's omelette while I took notes, and she invited two friends, Odile and Robert, over one evening. As we got started, Claude and Odile said that I should tell the reader to make sautéed potatoes. I stopped them right there. Sure, I said, a lot of people would know what sautéed meant, it was a common term in cooking. But then again, some people might not and I wanted to make the recipe as specific and detailed and possible. I feel, as always, that it is better to know too much than too little. So here are my notes for Panou's potato omelette for four:

Let's start with utensils and ingredients.

1. Skillet - Two frying pans of the Teflon sort would be better, but one will do. If you have two, you can cook the potatoes in one and then the final omelette in the other. The skillet should measure about ten inches (25 centimeters)in diameter, across the center from side to side. If you want to adjust your ingredients and make the omelette for only two persons, also adjust the size of the frying pan, make it smaller. Panou's omelette should not be flat like a regular omelette but should have about the thickness of a pie toward the center.

2. Plate - At the end, when the omelette is done, you are going to put a dish over the skillet, face down, and then turn the pan and plate over in one movement, leaving the bottom of the omelette face up. So you need a dish big enough to fit face down over the frying pan.

3. Potatoes - Four medium-sized potatoes or six small ones. Choose potatoes that are firm.

4. Eggs - Seven eggs of the best quality. Panou fed his chickens wheat in early morning and late afternoon, and the rest of the time they ranged over lush pasture that was never treated with chemicals. You can imagine how his eggs tasted. If you don't have your own chickens, make sure you choose the best eggs that can be purchased. It makes a difference.

5. A little cooking oil and a nut of butter (a tablespoonful, more or less) , salt and pepper.

Now we begin:

1. Peel, wash, and dry the potatoes. Starting at the top, slice them into rounds about the size of the sliced bananas you would add to your breakfast cereal.

2. Put a spoonful of cooking oil in your skillet and turn the heat to above medium but not top heat--about three fourths on your dial.

3. Pour the potato slices into the skillet. Different kinds of potatoes cook at varying speeds, so there is no set time for this step. Using a fork, face down, keep moving the slices around until they begin to turn a golden yellow. When they reach this stage, sprinkle a little salt and pepper over them, and then put a top cover on the skillet. This preserves the potato's natural moisture. Keep checking until the potatoes are done, using the taste test, and then turn off the heat. Put a paper towel in a plate and pour in the potato slices. Put another paper towel over the top and move it around, absorbing the grease from the potatoes.

4. Break seven eggs into a mixing bowl. Add a big pinch of salt and a pinch of pepper. Beat the eggs with a whisk or a fork for about 30 seconds until the mixture is uniformly yellow. Do not use a blender. (Claude used a fork.) When the eggs are well mixed, add a spoonful of water. This compensates for the evaporation of the eggs during cooking.

5. Put a nut of butter (a tablespoonful, more or less) in a second skillet or in the one you have cleaned of oil. Hold the skillet over a high heat. Move it back and forth, turning it left and right until the butter melts and coats the bottom but does not burn.

6. Pour in the eggs. Let the eggs settle for about four seconds and use the bottom side a fork to spread the mixture evenly. Then use a face-down fork, or the side of the fork, to move the liquid from the edges back toward the center as it cooks. Do this fast and continuously. In about eight seconds, when the omelette looks half-cooked, meaning it has coagulated into a soft custard, pour in the potato slices. Spread and flatten the slices into the egg with your fork. Your skillet should be fully covered with egg and potato. When there is almost no liquid left, turn off the heat. Careful, don't overcook. You want it to come out soft and tender.

6. Transferring the omelette to the dish requires a little agility but nothing you can't handle if you think it through first. Put some kitchen cloths on the counter to make a soft landing in case your flip gets out of hand. Then place the plate face down over the skillet. Holding one hand over the bottom of the dish, raise the skillet and flip it over. Now your omelette is ready for slicing and serving.

Claude started off by serving a Ramadan soup (she finished the omelette after the soup, at the last minute), which is a hearty vegetable soup eaten by Islamics in Morocco, in the evening, after a day of fasting, during the holy month of Ramadan. She served a green salad with the omelette. For dessert she had made an apple and walnut cake. These were delicious additions to the meal, but I'll save the recipes for another time.

Robert brought a white Burgundy, appropriate for the occasion--above average, but not extravagant, since we were only having soup and an egg dish. I opened a red Côte Roannaise to go with the cheese, a Coulommiers au lait cru sur paille.

"Thanks, Panou," I said, in benediction, as we finished a simple but wonderful meal.

P.S. We have carried on Panou's tradition of wheat-fed chickens and home-grown potatoes. |

| Next Letter: Eating the Wild Boar |

| |

|

|

| ©Copyright 2010, 2009, 2008, Pythia Press. All rights reserved. |

|